Survive the dividend drought

Leading blue chips and their army of small investors have suddenly been forced to make tough decisions.

This week the dividend kings — our major banks — were finally forced to deal with the issue.

For months now we’ve been warned that dividend cuts of more than 30 per cent were on the way for all stocks.

With one of the highest dividend payout rates in the world, our leading blue chips had reached a critical juncture.

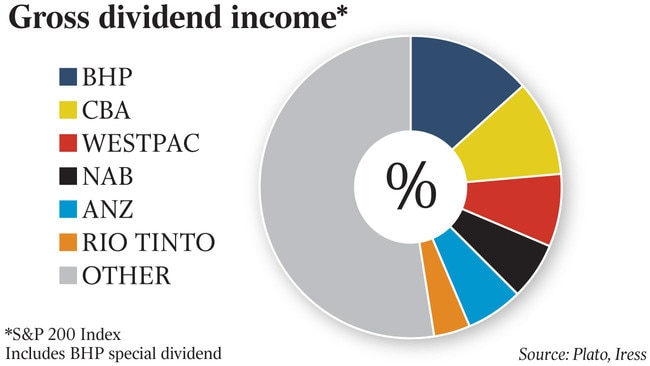

But for banks — which pay one dollar in three of all dividend payments across the market — there was double pressure. On one side profit falls of 50 per cent-plus meant big dividends payouts were no longer sustainable. At the same time the banking regulator was actively warning against letting capital run down in the face of a looming global recession.

What to do? Unlike supermarkets or miners which even under these exceptional conditions can offer the promise of resilient profits in the months ahead, bank investors know that share-price-boosting profits are a long way off — and they have primarily invested for income.

When the crunch came, the reporting calendar forced NAB to make the opening move. The bank’s newly minted CEO Ross McEwan announced NAB would pay a dividend, but it would be cut by nearly two-thirds: $850m was on its way to the bank’s 570,000 small shareholders.

Three days later ANZ boss Shayne Elliot made his move: no dividend announced.

In the months ahead dozens of companies will be forced to make similar decisions: move according to the textbook and scrap the dividend, explaining the need to conserve capital.

Or do something that might be a lot more streetwise: keep paying a dividend though it makes little sense economically — pay it even if you have to raise money at the same time (as NAB has done).

We cannot underestimate the importance of dividends to the local investment community — a generation of investors were told for decades to accumulate dividend stocks. They were told that the franking system, which boosts the ultimate returns of these dividends, meant there were few better choices for long-term wealth accumulation.

Importantly, the survival of the franking system means that even a reduced dividend can offer an income that is still better than almost anything else the wider market has to offer.

Cash rates are hopeless, bond rates are at record lows, and property rental yields are low and going lower.

Against this backdrop, even if the market’s overall dividend yield dwindles from more than 4 per cent to much lower levels, those who can pay a dividend at all will be supported.

Looking at the NAB situation a little more closely, the bank (after a fierce selldown) is currently trading on a yield of more than 5 per cent. That’s in a market where cash gets less than 0.01 per cent.

So don’t be surprised that many in the market — both company leaders and private investors — will hang close to the dividend tap.

More broadly, investors may swing towards non-bank dividend payers who may copy NAB in paying out dividends with one eye on satisfying smaller shareholders, especially retirees.

A revived hunt for dividends among companies that can find the resources to pay out could trigger what Paul Winter of UBS recently suggested would be “the biggest trade in the market”.

Among this group is Telstra and the supermarket leaders Coles and Woolworths. The major utilities can be counted here, including AGL, and industrials such as Amcor, Brambles and Wesfarmers.

Joining this list are the big two miners BHP and Rio, which have better operating conditions and the ability to deliver on their expected yields of more than 6 per cent.

More broadly though, the pandemic crash may change the nature of our market as the dividend payers may increasingly lose ground to “growth” companies that simply “do better” on the sharemarket and bring home the bacon in the form of rising share prices where dividends matter much less. The exemplar here is CSL. The blood products group has a microscopic dividend yield of less than 1 per cent — but then again, it has been barely dented by the crash and the share price is up 56 per cent over the last 12 months which would do very nicely for any investor, retired or not.

Income investors such as Peter Gardner of the Plato fund management group have cried foul over dividend cuts in recent days and called for Wespac, among others, to put income seekers higher on the corporate agenda. (Westpac reports on Monday.)

But others are looking in different directions: financial adviser Sue Dahn of Pitcher Partners says it’s time for investors to review the market through a post-crash lens. Dahn says investors must accept conditions have changed considerably and take what they can get — if it is less dividends and the prospect of a rising share price, that will have to do. (Read Dahn’s column on opposite page.)

For now the blue chips, led by the banks, are testing the water on cutting dividends. ANZ says it has merely deferred its dividend decision until August — though such a line is no consolation to anyone who had plans for interim dividends that never came.

NAB has been blasted for perpetuating a merry-go-round where it raises $3.5bn and distributes $850m in dividends at the same time. It’s fair criticism and the bank is unlikely to try this more than once.

Investors too are being forced to test the waters. The two groups have one thing in common — they have little choice.

The Australian sharemarket is addicted to dividends and it might not be healthy.