Why did you sell that time? What did you hesitate in buying the other time? What did you act hastily, or too slowly, or not at all?

The best investment presentation I’ve ever seen — and I’ve seen hundreds of them — came from Kerr Neilson, the legendary founder of Platinum Investments: the funny thing is, I didn’t realise it at the time.

Neilson was addressing an investment conference and like everyone else I was very keen to hear any pointers the billionaire fund manager had to offer on successful investing.

But instead Neilson launched into a measured analysis on investing bias. I sat patiently through the address, suppressing yawns and furtively reading emails. Basically, I was terribly disappointed he didn’t offer us stunning insights into his best and worst stocks.

But hours later the penny dropped, I came to realise that Neilson had nailed it: the more aware you are of your biases the better you will invest.

Ever since, I’ve tried to be constantly aware of bias when it comes to investing.

More recently there is a growing body of published work about the broader issue of bias as it affects wealth accumulation — how we set our financial goals and why we often don’t get them right. Again, it is clear our financial plans can let us down due to bias this time in the form of rushed thinking and incomplete information.

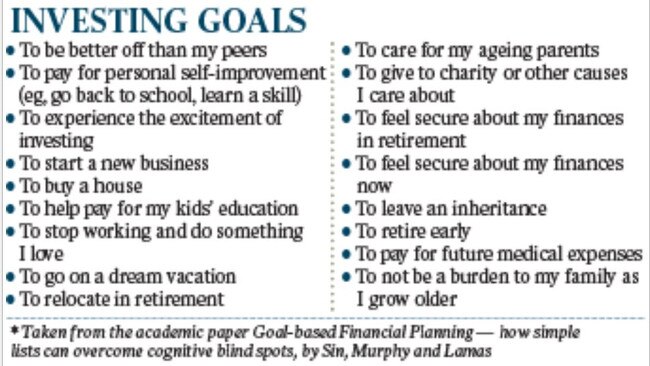

Now a prize-winning paper from a group of academics (Goal-based Financial Planning — how simple lists can overcome cognitive blind spots, by Sin, Murphy and Lamas) has revealed some key insights. The three academics all work for the Morningstar group.

● A simple comprehensive “master list” that gets down on paper every issue that might be relevant to achieving your financial goals can be enormously helpful. For example, you might say what you want in the future is the holiday of a lifetime, but in fact what you really want is to give up your job and do something you love.

● Typically, in making a list of our financial goals, we literally forget to mention half of them. That’s what’s called “present bias”. But 70 per cent of all investors will change their top three goals if they take time to consider a master list rather than shoot from the hip.

● The more we get our financial goals to align with our individual circumstances, the more successful we will be in chasing them. If you say I want to retire comfortably, that is a standard response. If you say I want to retire in a house I will build in a spot by a lake that I visit every summer, that is a personalised response. The study shows personalised goals are more likely to be fulfilled than generic goals.

● Crucially, we must include non-financial goals in getting to where we want to be. The study found that when people changed financial goals after considering a curated master list instead of blurting out the first items that came into their heads “half of the revised top goals were about emotions”. Suddenly items such as “feeling secure about my finances”, and “to not be a burden on my family as I grow older” appeared as goals when previously they were not on the agenda. It seems good sense to base wealth plans on hard numbers. But a non-pecuniary aspect of financial planning is more important than we thought. As the academics would put it: “Emotions are — and should be — considered a critical part in constructive financial decision makings”.

It’s an important lesson, whenever you sit down to make or revise your wealth plans. Of course we should learn as much as we can about shares, property, asset allocation and returns on capital, but it is not enough.

We need to think beyond those hard numbers to be aware of what we may have left out or what we overemphasise just because that issue is “top of mind”.

See the table for the 17 items on the paper’s master list — review your plans against them and you will do better.

The more comprehensive and accurate that assessment, the better chance you have in achieving financial goals. After all, this why most of us invest in the first place.

Once you understand the basics of investing then a huge part of the difference between success and failure is based on bias: you might call this overcoming blind spots when it comes to money.