Home calls and investors answer

FIRST-time buyers have been squeezed out of the housing market.

SOMETHING entirely new is happening in the property market: investors are dominating the action and it’s going to have enormous ramifications for property prices, rental yields and ultimately our financial system.

Take these two points for a start: First, in NSW (traditionally our hottest residential market) the percentage of home buyers who are first-time buyers is now down to 9 per cent. Second, a CBA survey earlier this week of 1000 existing home owners found that nationally 47 per cent of respondents had bought or were planning to buy a property (in NSW the figure reached 54 per cent).

So, if you think about that for a second, investors who already make up more than 40 per cent of all new home loans are indicating they have barely started on the house purchasing binge which has been triggered by record low interest rates.

Why the rush into property? Just now residential property is particularly seductive, especially for those who find the sharemarket too difficult, too risky or a combination of both (despite the ASX having risen by roughly 20 per cent annually over the past two years).

This current attraction of property is particularly keen among older investors who will need income in the years to come: With cash on deposit earning a measly 3 per cent or so, an investment property should return at least 4 per cent per annum (that is, you should get 4 per cent of your purchase price back in rent over the course of a year) and there is the distinct prospect of price appreciation to go with the annual rental income.

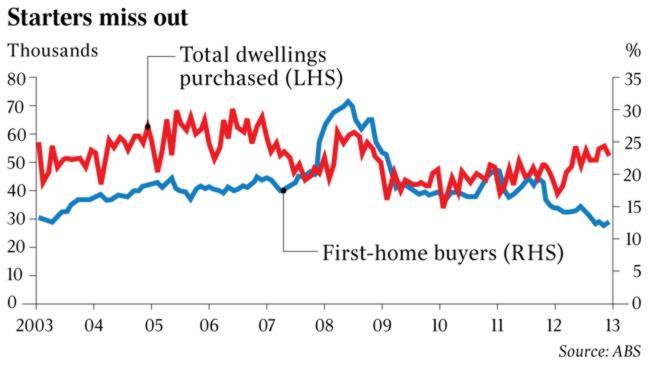

While this headlong rush gathers pace, first-home buyers are being squeezed out. The 9 per cent representation in NSW is the worst state yet seen but the rest of the nation is not far behind, the relevant percentage representation for first-home buyers is just 12 per cent in Victoria and Queensland.

Now to put this in perspective, just six years ago (spurred by Kevin Rudd’s home grant scheme) first-home buyers represented almost 30 per cent of all buyers in the home market. Early this year this level of first-home buyer action had drifted to below 15 per cent, as the graph shows.

Investors are rushing into property as a feasible income-producing investment for the long term. As they do so they push up prices and make it harder for people to buy entry-level property. This factor automatically produces more renters, which allows property developers to promote the fact there are more renters!

That is a factor which should, in theory, make investing in property more attractive as it enhances the possibility of deriving income from the investment.

What’s more, investors are further encouraged by the historic government decision in 2007 to allow SMSF trustees not just to invest in property, but to borrow money to finance their plans.

Looking more closely at the figures which underpin this scenario, the affordability issue is crucial.

In Melbourne it costs 50 per cent more each month to have a home or unit on a standard mortgage than to rent the same property. The picture is repeated at a less dramatic scale across the country ... remember this is all happening with the lowest mortgage rates since the 1960s.

If you are sceptical about the suggestion that it costs half as much again to take a mortgage on a home than to rent it, examine briefly the figures from property research company Residex.

They say the median value of a Melbourne house is $610,000 and the average household income is just a touch under $100,000 ($9796) while a monthly loan repayment on the average house will be $2948 against average monthly rental payments of $1889, a 50 per cent difference.

Is there anything wrong with this picture? There are two ways to look at it. From a societal perspective we are hurtling towards a European model where in metropolitan centres huge tracts of the population live in public or landlord-owned housing and they will never own their own home.

However, from an investment perspective it is undeniably attractive compared with leaving money in cash, at least in the medium term.

You might chime in at this point and say the figures are hard to believe and I concede the Melbourne example is the most extreme one. It’s more like 40 per cent in Sydney or just 11 per cent in Brisbane and Adelaide, but it’s beyond doubt that last year’s national upswing in house prices terminated the brief spell where in some suburbs it was cheaper to buy than rent.

Others might suggest first-home buyers should take the initiative and do it hard to get into their first owned home; after all it’s going to be worth it in the long run. If you own your house you get some real financial security. Well, no doubt a slice of the market is in this category but it’s also safe to assume the simple mathematics here are just pushing the raft of home ownership further out from the shore for many people.

Where does it lead?

Residential property prices move in cycles, and in Australia we’ve had the softest of setbacks in home prices: We missed the 40 per cent price plunge the US experienced in the six years to 2012. Usefully we have not had a building boom in residential property, the oligopoly of the big four banks makes sure of that. Some would also argue any potential building boom was also hampered by an oligopoly in the housing market, especially among the bigger unit developers.

Nonetheless, the built-in expectations of future price appreciation in our residential property market may face disappointment in the years ahead if property prices amble along at stable levels rather than the powerful leaps of previous decades and this is entirely possible in an era of below trend growth and rising unemployment.

More important for the moment is the seismic shift occurring in the market. First-home buyers are disappearing and investors are moving in - until now this pattern has been emerging at a reasonable pace.

Now a combination of signals and survey suggest we are about to see a major acceleration of pace. As this occurs it will initially at least push up residential prices, but it could dampen the prospect of improving yields (residential yields have barely moved for a decade).

Certainly if more suburbs become more expensive then yields will do little better than stabilise. Though I said earlier average rental yields are around 4 per cent ... averages can be misleading. An expensive area of one of our leading cities can offer annual yields below 3 per cent while a less expensive area can yield up to 5 per cent: This changed calculation can make a big difference to the numbers for an investor especially if overall prices are only growing at a gradual pace.

So, more expensive suburbs mean weaker rental yields and that’s before we even think about what might happen to those investor calculations when interest rates rise again, as they will.

Finally, the very people who are sinking their savings into residential property seeking long-term income will have to face their sons and daughters who can’t buy a first home and are hoping for a bit of help on that front ... unfortunately statistics on that sort of activity are not quite so easy to find.

James Kirby is managing editor of Eureka Report.

Trial Eureka Report FREE for 21 days. register now at www.eurekareport.com.au