Coronavirus crisis hits home for property investors

As the government looks to an aid package for tenants, housing owners face unprecedented pressures.

Certainly, the forecasters are getting bolder with their estimates for a projected house price downturn getting worse by the day.

With the best of intentions, the section of the Morrison stimulus package that dealt with residential property targeted the weakest link in the investment property chain — tenants at risk of losing their homes.

A six-month “moratorium” on evictions where tenants are facing “financial distress” is now in place.

Unfortunately, “financial distress” was not clearly defined in the package and as a result problems are rapidly emerging that have the potential to make a bad situation worse. As an economist might put it, the market has been “distorted” — and when this happens, uncertainty takes over.

At less than 4 per cent of registered property disputes, evictions have been relatively rare in our market.

But their key role is as a deterrent — the ultimate threat a property owner has if things go wrong with a residential investment.

When Scott Morrison announced the tenant protection measure a few days ago, he did not apply any matching relief measures for residential property owners. He had hoped parties “would sit down and work it out”.

Nothing of the sort happened. Bad behaviour, on both sides of the ledger, emerged in the sector within days.

Property owners reported tenants instantly seeking rent reductions or complete rent suspensions, knowing they could not be evicted.

Meanwhile, real estate agents were caught exploiting the controversial early release superannuation scheme the government has also just launched. One Ray White real estate office had actually added a new section to its “financial hardship application form” that inquired if the tenant was going to use the scheme.

The practice got a swift slapdown from the Australian Securities & Investments Commission, which said agents could face imprisonment with this tactic as it risks breaching corporations law.

Against this backdrop on Friday, the Prime Minister returned to the issue suggesting: “You will recall there was a moratorium on evictions. That doesn’t mean there is a moratorium on rents.”

But as Antonia Mercorella, the president of Queensland’s REIQ put it: “We understand that the Treasury and cabinet is still working on a complete package for residential property, yet until this is sorted out we are going to have confusion and fear.”

As Mercorella explained earlier this week: “For property owners it’s not just a matter of pressing pause on mortgage repayments to set and forget for six months.

“Many mum and dad investors can barely cover the various costs associated with owning an investment property even with rent coming in — so they may not have any other choice but to sell their properties. It puts many at risk of bankruptcy.

“Consideration also needs to be given to those self-funded retirees whose only source of income is derived from an investment property.”

Among the ideas being pushed by property representatives is a “TenantKeeper”-style package that would be a version of the JobKeeper program for property — the logic being that if businesses are being paid to keep employees, property owners could be paid to keep tenants.

In fact, the Queensland state government has already enacted a very limited version of the idea with a “rent relief package” where cash-strapped owners will directly receive a maximum of $2000.

Whatever the final details, it is likely the package being prepared by the government will try to make the existing system of residential property support work more effectively.

Comparisons with the emerging solutions in commercial property are unlikely to be useful since wage subsidies are a key factor in these negotiations, where landlords are expected to reduce rents in line with reduced turnover experienced by business tenants.

In contrast the residential support system hinges on banks offering mortgage freeze arrangements where a property owner who does not receive rent can defer payment to a later date. The issue here is that the investors will simply owe more in the future, as the borrowings compound.

For more than a million residential property investors, the reality is that property investment as an income-earning investment was barely working anyway.

In the larger cities, where the bulk of activity occurs, rental yields are often 2-3 per cent. Once you subtract expenses and land tax, investors are lucky to make any income at all from properties. In reality, almost the entire investment proposal has been based on the assumption that prices would rise.

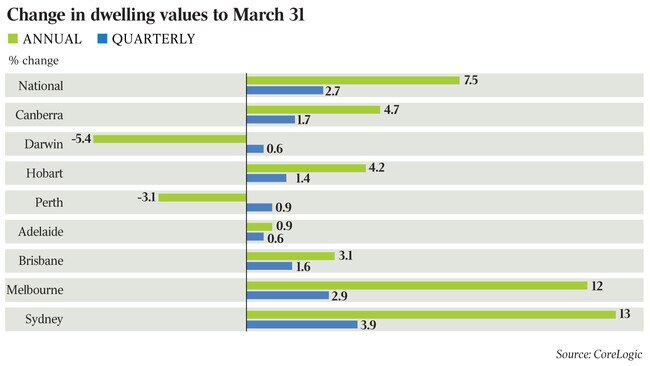

Nonetheless, investors had just started returning to the market in significant numbers after the difficult period in 2018, when prices fell from the top to bottom by about 10 per cent. Investor home loan growth rates have been buzzing along at an annualised level of near 15 per cent.

Now with unemployment rising and incomes falling, the very mechanics of the residential property market are in peril.

Analysts are suggesting house prices — which are up about 9 per cent over the past 12 months — could ultimately fall anywhere between 10 per cent and 20 per cent.

In the weeks ahead many investors may muddle through on a loss-making basis.

The trouble will start when the various six-month moratoriums on rental evictions and rental payments come to an end.

At the same time, prices in residential property will almost definitely be significantly lower.

It all looms as the worst possible scenario, it’s going to take skill and fortitude to see it through.

Are property investors sitting where sharemarket investors sat six weeks ago? That is, on the edge of a cliff?