Can Australia afford an ageing workforce?

The Australian economy must adapt in the face of an ageing workforce and growing numbers of retirees.

As a nation, can we afford to grow old? What does it take for a country to ensure its residents can retire in security and comfort?

Obviously, a country must be economically productive for its population to grow old in comfort.

If the retiree cohort grows faster than the working age population fewer workers must create more GDP to finance the retirement of the ageing population.

This is tricky but not impossible. Japan has dealt with a shrinking working age population for decades. Automation and robotics helped boost GDP nonetheless.

But the social contract was also renegotiated. Japanese women traditionally stopped working once they got married.

Economic necessity and female empowerment ensured that women continued working. Since no country aged faster than Japan these working women provided a much-needed economic boom.

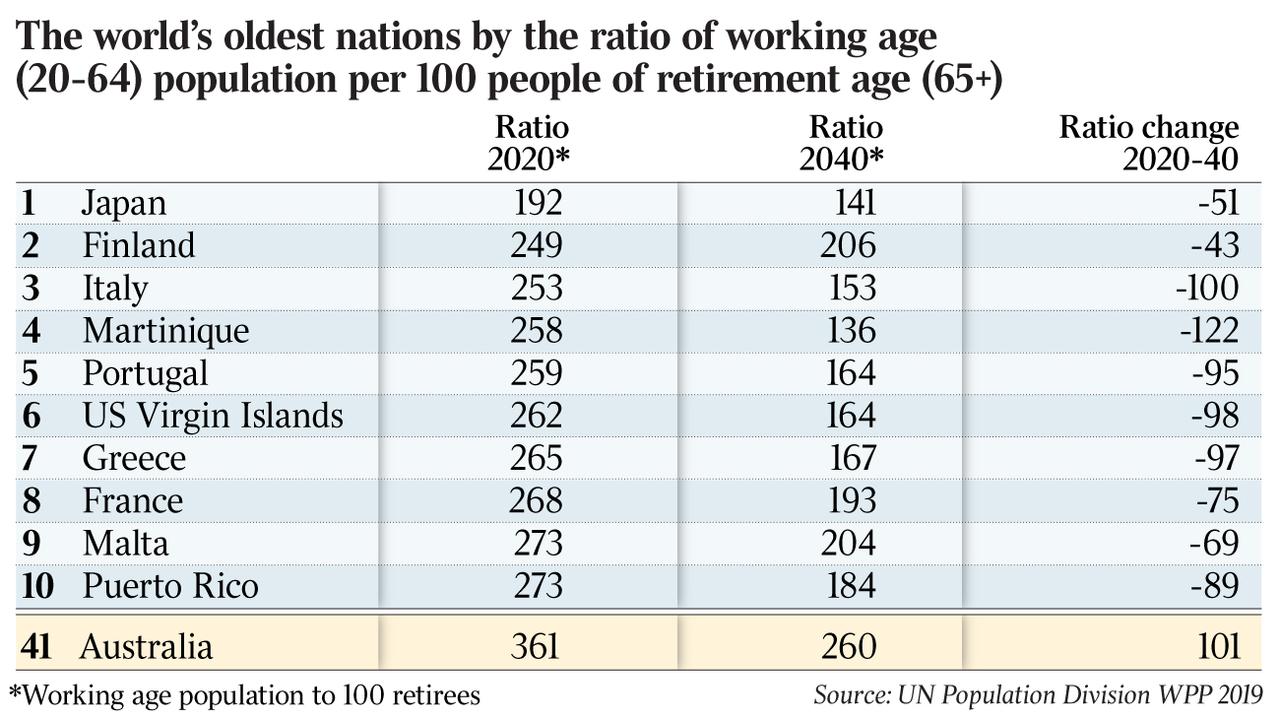

A solid 367 Japanese of working age were available in 2000 to finance 100 retirees.

Fast forward 20 years to 2020 and this ratio is 192. This makes Japan the country with the lowest ratio of working age residents to retirement age residents.

Put differently, every Japanese person of working age must finance half a retiree. That’s quite the burden. Without a sharp increase in female workforce participation Japan would be in a lot of trouble now.

However, things aren’t going to get any easier for Japan. By 2040 a shockingly low 141 people of working age must provide for 100 retirees. The Japanese at some stage might be forced to open their country up for skilled migrants.

How does Australia compare to these figures? Today 361 working-agers look after 100 retirement-agers. We are now where Japan was in 2000.

Because we (unlike the Japanese) run a skilled migration program, we won’t see the worker to retiree ratio plunge as fast and deep as our Japanese friends.

By 2040 we will only see the ratio drop to 260, which is significantly above the Japanese figure for today.

Relative to all other countries we are actually doing really well. We are currently the 42nd most disadvantaged nation in the working age to retirement age ranking and 2040 will see us drop down to rank 55, meaning we are improving our relative position.

Australia is doing a great job in dealing with the demographic wave of an ageing population.

While this is a big challenge for Australia there is one nation that is dealing with the same problem at a much larger scale and is willing to do everything in its power to fix their demographic problem.

By 2040 the Chinese population aged over 65 is going to double from today’s 172 million people to 344 million people. China will have to manage a retirement cohort larger than the entire population of the US today.

It is no wonder the Chinese are obsessed with “growing rich before growing old”. Traditionally families took care of their ageing relatives. Due to the infamous one-child-policy families are now much smaller and the burden (both physically and financially) of caring for older parents now rests on fewer shoulders.

A single working couple will often be forced to financially support themselves, one or two children and four ageing parents.

Since a nation can’t rely on an average working couple to finance up to eight people, the Chinese government finances the retirement of its population through a centralised system. Because China ages very quickly, the Chinese GDP must grow at an even faster pace to ensure the country grows rich before it grows old.

The Chinese look with awe at the Japanese who managed to accumulate a lot of wealth before the population grew old.

Chinese women are already much more involved in the economy than Japanese women were in the past. China therefore can’t create an equally impactful female-driven economic boost.

This means China must ensure their workers are more productive. China is willing to do whatever it takes to continue GDP growth.

Once the national construction industry in China slowed down they simply started building big infrastructure projects in foreign countries. One important goal of the one-road-one-belt initiative was to keep the Chinese construction industry engaged. As long as Chinese companies and Chinese workers are engaged, an infrastructure project will grow the Chinese GDP, whether it’s a dam in China or a railroad in Ethiopia.

What does all this mean for retirees in Australia?

First, we can be glad our ageing population issue isn’t nearly as urgent as in other economies to begin with. Second, we are actively importing skilled labour, which boosts GDP by allowing our businesses to grow when they need to.

The skilled migration program is assisting our retirees, especially those who rely on the pension, to live a secure retirement.

Most importantly, we must admit that the introduction of compulsory superannuation in Australia was a demographically wise move.

Many countries, like China, still manage a centralised retirement bucket out of which pensions for the whole retirement cohort are paid. Such systems can only withstand so much demographic stress. Once they fail, retirees’ pensions shrink or simply disappear.

It’s therefore very smart to force people to manage their personal retirement buckets.

If you earn enough throughout your working life, superannuation alone can be enough to finance a dignified retirement. Any worker who managed to do so has taken the burden off the state.

Give yourself a pat on the back if your fall into that category.

However, some Australians in low paid jobs will struggle to collect enough in their super. How do we ensure these low paid workers can have a dignified retirement?

Is a government funded pension for the poorest retirees the best solution? Should the state top up the super contributions of the poorest workers to a certain minimum each year — maybe as part of some elaborate national wage insurance scheme?

As long as the Australian economy grows in a healthy and sustainable way the number of Australians who can’t finance their retirement will be small enough for federal intervention to be a feasible solution — even in a future with fewer workers and more retirees.

Pension systems that rely on a centralised bucket will struggle much more than Australia from the demographic shift towards smaller workforces and larger retirement cohorts.

Australia stands an excellent chance of continuing to be a great country for retirees even in the face of big demographic shifts.

-

This is the fourth in a series by The Australian and The Demographics Group looking into retirement in 2030.

The series has been created in partnership with MLC, part of the NAB Group. Read our policy on commercial content here.