What really went wrong in Britain

Expect criticism as well from America’s big-government conservatives worried M. Truss’s program might succeed. As the blame-game continues, let’s step back and recount what has really happened in Britain:

***

It’s wrong to say Britain plunged into crisis Friday after Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced a large tax-cut package, because Britain’s economy was already a mess. The pound had lost about 17% of its value against the dollar since the start of the year, borrowing costs were rising, and the economy was expected to be the slowest grower of any large country.

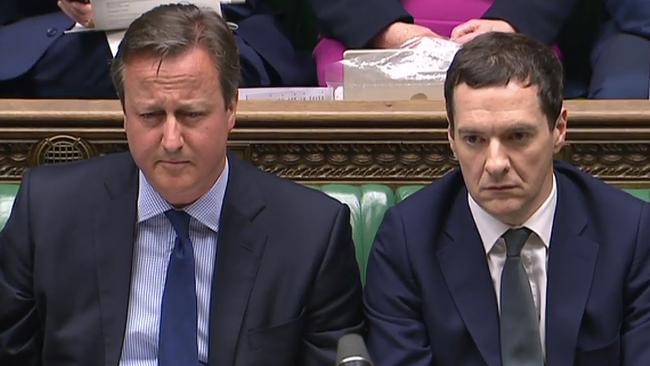

That malaise was the culmination of 12 years of big-government conservatism from successive Tory Prime Ministers. David Cameron came to power in 2010, in the wake of a financial panic that hit Britain hard, promising an economic revival. He and Chancellor George Osborne implemented some pro-growth policies, such as a corporate tax-rate cut and a welfare reform to encourage work.

But their legacy was to entrench a misleading view of “austerity.” Understanding that government spending of 44% and debt approaching 70% of GDP (according to IMF data) after the 2008 crisis needed to come down, the Cameron administration claimed to be tightening the government’s belt. They leaned into the view that near-term fiscal balance rather than medium-term economic growth is the only path to policy credibility. Tax-rate cuts were offset by clawbacks such as stingier exemptions for pension saving and business investment to preserve revenue.

Spending restraint was achieved via scattershot attrition of the government workforce and partial outsourcing of government functions. Britain never had a debate about what the role of the state should be, and the policy wasn’t all that austere anyway. Spending fell only to 39% of GDP by the end of Mr. Cameron’s tenure, slightly above its pre-2008 level. The economy grew, but skewed toward a few industries (especially financial services). A productivity crisis developed as investment faltered, depriving the economy of the means to sustain wage growth.

Mr. Cameron was followed by Theresa May, who embraced a form of even-bigger-government conservatism. Most of her tenure was consumed by debates over Britain’s departure from the European Union, but she found time to talk up industrial policy and threaten to raise tax rates.

When Boris Johnson became Prime Minister on a promise to finish Brexit, he ushered in biggest-government-yet conservatism. He planned a “levelling-up” agenda that would boost economically disadvantaged regions via extravagant government spending. He all but abandoned post-Brexit deregulation.

Following the fiscal shock of the pandemic, Mr. Johnson’s first instinct was to raise taxes—via a 2.5-percentage-point increase in the payroll tax, and by letting accelerating inflation tip individuals into higher tax brackets. Former Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s last budget by some counts was predicted to lift tax revenue to its highest level relative to GDP since the 1950s.

Two other threads tie together all three Tory administrations. One is bad energy policy. Mr. Cameron embraced climate-change dogma to soften the party’s image. The slogan became “Vote Blue, Go Green,” a reference to the Tories’ blue branding. He opposed coal power and only tepidly supported nuclear, and once in office introduced new subsidies for renewables. A belated attempt to permit shale-gas fracking failed.

Mr. Johnson threw himself into net-zero carbon goals with reckless abandon. Late last year he unveiled a national strategy that would include banning internal-combustion-engine cars and forcing households to pay thousands of pounds for new home heat pumps.

All the while energy prices kept rising, dragging on the economy. None of the three Prime Ministers was ready to admit their energy policies might be the problem. They bequeathed to Ms. Truss this month an electorate staring down the barrel of an 80% increase in household energy costs in October.

The other thread is bad monetary policy. The Osborne Treasury and the Bank of England under Governors Mervyn King and Mark Carney set the tone by “looking through” above-target inflation for four years from 2010-13, and again in 2017-19. The central bank ignored its price-stability mandate in order to hold interest rates at historic lows while suppressing government borrowing costs with quantitative easing.

This stoked asset-price inflation, especially in housing, while suppressing productive investment and real wages. Inflation-adjusted pay fell 6.7% from 2009-14.

Mr. Carney’s successor Andrew Bailey poured on generous monetary stimulus during the pandemic, and he has been slow to withdraw it as the inflationary crisis deepens. One day before Mr. Kwarteng’s tax announcement, Mr. Bailey gave markets a bad surprise with a dovish 50-basis-point increase in interest rates rather than a 75-point raise that would follow the Federal Reserve’s lead and match the severity of UK inflation.

***

No wonder markets were primed to question Britain’s policy credibility when Mr. Kwarteng unveiled the new tax plan. Ms Truss and Mr. Kwarteng are calling time on the mistakes of their predecessors, and seem determined to pursue both tax-rate cuts and tax-code reforms and economic deregulation to spur productive private investment.

But investors have heard a lot of incomplete or misleading promises about pro-growth policies from recent Tory leaders. Even now Ms. Truss’s backbenchers, who didn’t want her as leader, are sniping at her and implicitly defending the Johnson-Sunak record of failure.

The point is that Britain was in an economic mess before Ms. Truss took office, and there is no alternative universe in which policies that have failed for 12 years suddenly would start working on the cusp of a global downturn. The choice is the gamble of a major policy overhaul, or the certainty of steeper decline.

So yes, US Republicans, do take note of Ms. Truss’s travails in Britain. The Tories squandered their reputation for competent, free-market economic management. They now find that it’s hard to win back at precisely the moment they and the country need it most.

The Wall Street Journal

Everyone needs a scapegoat in an economic crisis, and much of the world has settled on blaming British Prime Minister Liz Truss’s economic plans. The International Monetary Fund and the Biden Administration have piled on, which conveniently deflects from their failed policies that produced inflation and slow growth.