We know who’ll win the U.K. election, but why?

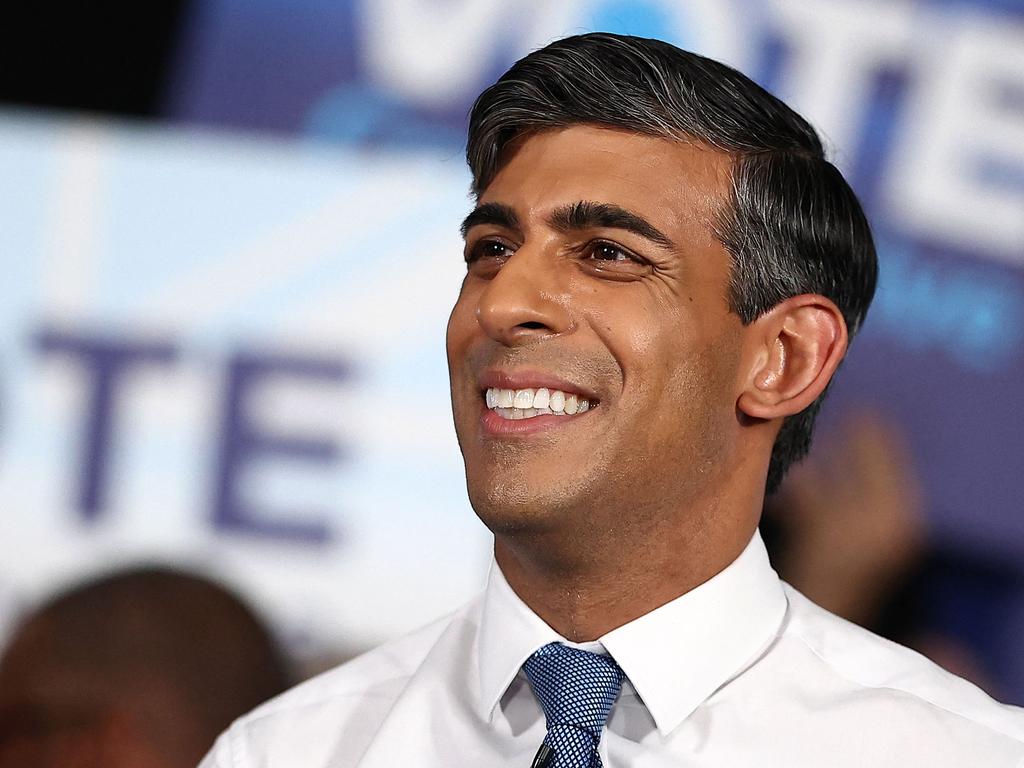

Which is precisely why he’s on track to lose big.

Opinion polls have predicted for the past few years that Mr. Sunak’s Conservative Party is cruising for a bruising in the next election whenever it would come. There are many explanations for this — we’ll get to some in a moment — but start with the fact that the party has been in power for 14 years. That’s too long in a democracy.

The Tories have exhausted their talent and whatever ideas they brought in when David Cameron first became prime minister in 2010. Intellectual drift set in long ago. That furlough scheme of which Mr. Sunak sounded so proud on Wednesday is representative.

Yes, in the early days of the pandemic, the public was reassured by a commitment from Mr. Sunak (then chancellor of the Exchequer under Prime Minister Boris Johnson) to use borrowed money to support millions of people prohibited from working. In retrospect, however, it’s clear Messrs. Johnson and Sunak fell back on this spending gimmick as a substitute for more serious, imaginative thinking about how to navigate the pandemic.

Government by gimmick became the norm, as with Mr. Sunak’s ill-fated “eat out to help out” scheme to subsidise restaurant meals after the first lockdown, which didn’t boost the economy much but allowed critics to claim that Mr. Sunak was encouraging the virus’s spread. The gimmickry has continued with schemes such as a plan to ship asylum claimants to Rwanda to solve Britain’s illegal-immigration crisis.

Meanwhile voters ask: What has Mr. Sunak done for me lately? The answer is an economic record of anaemic growth, inflation, high taxes and a host of other unresolved problems ranging from illegal immigration to weekly anti-Israel protests in London that the government seems helpless to curtail.

As a consequence, the outcome of the July election isn’t much in doubt. It’s hard to imagine anything other than a Labour Party administration run by that party’s leader, Keir Starmer, although opinion polls leave open the question of how wide Mr. Starmer’s margin in parliament may be.

The real prizes will go to whoever comes up with the more compelling explanation for the election result. This is a game members of both parties will end up playing in an effort to nudge policy in the direction each party’s different factions prefer.

On the Labour side, it’s clear from the outside that Mr. Starmer is leading the party to victory by being profoundly and convincingly boring. Having jettisoned the radical left-wing economics and antisemitism of his predecessor as party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, Mr. Starmer has adopted a don’t-scare-the-horses strategy of disavowing any proposal that might prove at all controversial. Out is the pledge to spend £28 billion a year on green energy; in is a promise to spend 2.5% of gross domestic product on defence potentially sooner than the Tories would.

Yet the leftward wing will be tempted to push hard on Mr. Starmer in a spirit of not allowing the Tories’ electoral crisis to go to waste. He already faces periodic revolts as he tries to tamp down the antisemitism exposed by the left’s protests against Israel’s defensive war in Gaza, and expect escalating demands on matters ranging from labour regulation to transgender issues.

The Tories face the harder task, however, due to a surplus of potential scapegoats. The preferred object of blame will be Liz Truss, who preceded Mr. Sunak as prime minister and served barely six weeks. Ms. Truss constituted the only attempt the party has made since 2010 to return to its Thatcherite roots on economic policy. But she marched with her proposed supply-side tax reform right into the buzz saw of an energy crisis exacerbated by an array of bad pre-existing economic policies.

Mr Sunak and other big-government Tories — which is much of the party’s current caucus in parliament, but perhaps not a majority of the base — blame Ms. Truss for the ensuing economic disasters (especially higher interest rates on mortgages) even though her tax cuts were never enacted and Mr. Sunak’s high-tax alternative has proved a conspicuous flop. One can just as easily blame the Tories’ impending defeat on their refusal to adopt a Thatcherite economic revival program much sooner, and on serial policy kowtowing to liberal media opinion on matters such as immigration — the sort of obeisance Ms. Truss, for all her flaws, never paid to her ideological opponents.

All of which means that voters head into this election knowing who will probably win, but with considerable debate surrounding why. It sets the stage for a sleepy election and a tumultuous five-year term following, on both sides.

The Wall Street Journal

Presumably it wasn’t an accident that in announcing the date for an election Wednesday — the vote will be July 4 — British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak started by touting his pandemic furlough scheme. That program, which shovelled money at workers forced by lockdowns to stay home, seems to be his proudest accomplishment during his time in the upper echelons of the government.