‘Their goal is to make you feel helpless’: little room for dissent in Xi’s China

After one man was snatched off the street for tracking protests online, he spent four years in custody and remains under close scrutiny.

Xi Jinping’s crackdown has snared women planning protests against sexual harassment, human-rights lawyers once given leeway and Marxist students advocating workers’ rights. Many have endured lengthy detentions and various forms of psychological pressure.

“Their goal is to make you feel helpless, hopeless, devoid of any support, and break you down so you begin to see activism as something foolish that doesn’t benefit anyone, and gives pain to everyone around you,” said Yaxue Cao, a Washington-based activist who runs China Change, a news and commentary website advocating for human rights. “In so many cases, they are successful.”

After Mr. Lu was snatched off the street, he spent four years in custody, his girlfriend left him, and, since his release in June, he said he has been kept under close watch by police. He struggles to find steady work, he said, and suffers from depression. His landlord recently asked him to move, he said, citing pressure from authorities.

The experience keeps him far from his past documentation work. “If you’re lucky, they’d detain you within a month, or if you’re unlucky, within a week,” said Mr. Lu, 43 years old. “There’s no point.”

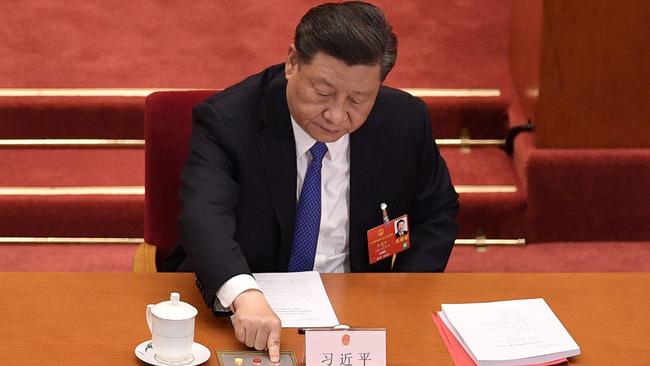

For years, the Communist Party grudgingly allowed a limited role for NGOs and activists, from environmentalists to labour organisers, to contribute policy ideas and tackle social problems. Under Mr. Xi, such work became solely the party’s domain. Modern surveillance has made it easier to hound anyone trying to perform that role outside of party control. China’s annual national spending on public security has nearly doubled since Mr. Xi took power in late 2012, reaching the equivalent of about $211 billion in 2019 at current rates, according to government figures.

Mr. Lu recounted his life in interviews with The Wall Street Journal, giving a detailed picture of the government’s tactics. The Journal corroborated much of his story through court documents and interviews with his friends and lawyers involved in his case. His account is consistent with other cases documented by human-rights activists.

Mr. Lu, who considers himself a record-keeper rather than an activist, said speaking up was a way to resist government censorship and to protect himself. “Being silenced would mean they can act brazenly and lock you down,” he said.

Police and judicial authorities connected with Mr. Lu’s detention, trial, imprisonment and subsequent surveillance didn’t respond to queries about his case.

Internet explorer

Mr. Lu was born in the impoverished southwestern province of Guizhou, where his father ran a seedling farm. He was a shy boy, and his parents sent him to live with different families to learn how to better interact with people. He was bullied in school, he said, and struggled with his studies. At 19, he went to prison for about six years after stabbing and wounding someone. He said he was standing up for a friend who had gotten into a fight.

After his release in 2002, Mr. Lu drifted from job to job, working in factories and construction. He discovered “dark folk,” music that mixed folk and industrial styles, and devoted hours online following his favourite Finnish and German bands. His moniker, “Darkmamu,” paired his musical interest with the Romanisation of the Chinese word for numbness.

“I saw no hope in anything and had no direction in life,” he said.

That began to change in 2011, when he tuned into social-media chatter about such Chinese activists as dissident artist Ai Weiwei. Censorship on China’s Twitter -like Weibo microblogging platform was relatively loose at the time, allowing more open discussion about social issues and criticism of government policies.

In April 2012, Mr. Lu raised a banner along a Shanghai thoroughfare calling for China’s leaders to publicly declare their personal assets, a way to curb corruption. He also called for the right to vote. Police chased him out of the city, he said, and when he returned, they detained him for 10 days.

Demonstrations flared across China that year, including high-profile protests against power and copper plant projects. Mr. Lu, who moved to the southern city of Fuzhou, scoured social media and began to realise the scale of national unrest. He said he decided to document as many demonstrations as he could.

“It wouldn’t change the broad trajectories of history,” he said, “but for me, I felt like I was doing something that meant I haven’t lived in vain.”

What is your view on Beijing’s crackdown on dissent? Join the conversation below.

Mr. Lu sifted through online chatter, images and videos of public unrest, posting his findings on Weibo, he said. He sharpened his abilities to cross-check information. He quit his job at a plastics factory, he said, and started a blog with a university student, Li Tingyu, who admired his work before she became his girlfriend and collaborator. They raised donations that supported full-time research, and their work drew attention abroad.

Police showed up at the couple’s apartment in the southern city of Zhuhai, Mr. Lu said, to warn them against continuing to publish their findings. Mr. Lu said he believes what followed was government-directed harassment: Their landlord refused to renew their lease. Strangers knocked on their door and claimed they were the new tenants. One day, they lost running water.

The couple moved to Dali in southwestern China, where they isolated themselves from family, friends and acquaintances. Authorities eventually found them there.

On June 15, 2016, the couple posted a tally of 94 demonstrations, including 27 protests by workers airing such grievances as unpaid wages. Later that day, they were picking up an online-shopping delivery at a courier station when they were captured by police and hustled away in separate cars, Mr. Lu recalled.

Days later, friends and supporters sensed trouble. Human-rights lawyers learned Mr. Lu and Ms. Li had been accused of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” The charge was commonly used for disorderly conduct such as damaging property. In 2013, it was expanded to include online behaviour by defining the internet as a public space.

The couple had compiled a data set comprising 67,502 protests that spanned June 2013 to June 2016, according to a 2019 research paper by Zhang Han, now an assistant professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and Jennifer Pan, a Stanford University assistant professor who studies authoritarian governance.

Through their blog, Mr. Lu and Ms. Li drew broad attention to protests in China, Ms. Pan said, “which is precisely the information government censors want to suppress.”

After Mr. Lu’s arrest, investigators waved copies of his social-media posts at him. “Why do you collect and publish this information? What’s the purpose?” Mr. Lu recalled an official asking him. He said he was documenting history.

Through the weeks of interrogation, Mr. Lu said, his thoughts often drifted to his girlfriend. He worried about who would take care of their pet, a tomcat named “Little Yellow Fur.”

Prosecutors and police pressed Mr. Lu to plead guilty, which typically is rewarded with a lighter sentence. He said officials brought his father to the detention centre hoping to persuade Mr. Lu, but he refused to acknowledge wrongdoing.

In November 2016, the journalist advocacy group Reporters Without Borders and French television broadcaster TV5Monde jointly awarded Mr. Lu and Ms. Li a press-freedom prize for “their commitment to freely and independently-reported information in China,” work the couple did at a high personal cost.

Officials visited Mr. Lu the following April, he said, to let him know Ms. Li had been convicted and given a suspended sentence. Mr. Lu said officials hoped he, too, would plead guilty. A copy of a Chinese court document related to Mr. Lu’s case, viewed by Journal, said Ms. Li had confessed.

Mr. Lu stood trial in June 2017. Prosecutors accused him of spreading false information. Mr. Lu, who denied wrongdoing, was convicted and sentenced to four years. His appeals were denied, according to court records.

In prison, Mr. Lu lived in a 12-man cell and worked 10-hour shifts sewing jeans, skirts and other apparel. He was paid the equivalent of a few dollars a month, he said.

Prison life wore on Mr. Lu. Last year, he suffered hallucinations and bouts of paranoia, he said. Prison officials offered counselling, but his symptoms persisted. About two months before his release, Mr. Lu said, he received a judicial notice forbidding him from setting foot in Beijing, Shanghai or Xinjiang.

After leaving prison, Mr. Lu moved in temporarily with his brother in their hometown. Police showed up to get his cellphone number. An official with the police department’s political-security arm would call him to ask where he was and what he was up to.

Mr. Lu moved to an apartment in the city of Zunyi, near his home village. Local police found him within a week, he said. He returned to social media with a new Twitter account, circumventing Chinese internet controls that block the platform. He listed his location as “hell” and posted an account of his detention and trial.

Mr. Lu tried to track down Ms. Li and eventually reached her mother. She said her daughter had married. Mr. Lu insisted on speaking to Ms. Li, and that night she called, sobbing as she apologised and said she had a new life, Mr. Lu recounted. She couldn’t be reached for comment.

In early August, police issued Mr. Lu a warning for using a virtual private network to circumvent Chinese internet controls. They seized his mobile phone and computer, which were later returned. He said police told him not to speak to news media.

Mr. Lu said he no longer felt safe in Zunyi. A couple of weeks later, he began travelling, first within Guizhou. He posted photos from his trips on social media, including shots of the lush cliffs along Guizhou’s Wuyang River and cattle on a grassy mountain in Fujian province.

Zunyi police kept close track of his whereabouts. An official would call him and ask, “What are you doing?” The phone calls and questions were repeated every time he reached a new city. Mr. Lu knew it was pointless to lie.

In late September, while Mr. Lu was staying at a friend’s apartment in the southern city of Guangzhou, officers called the friend and asked to meet. Mr. Lu then moved to a second friend’s apartment. The following day, police called the second friend who alerted Mr. Lu. It was too late. The officers were already at the door. They had made the call from downstairs.

The officers told Mr. Lu he had to leave Guangzhou. When he refused, they drove him to a police station, collected data from his phone and hauled him to the train station, he said. Hours later, the police texted a request: Send a selfie to prove he had reached his destination.

Police and justice-bureau officials in Zunyi regularly summon Mr. Lu to ask about his plans and warn him against circumventing internet controls.

While Mr. Lu has enough savings to survive for several months, he said he hopes he can secure a job soon. Police surveillance makes it tough to leave his hometown, where job opportunities are limited. Depression at times keeps him from sleeping more than a couple of hours a night, he said. In late October, his landlord, under pressure from authorities, told him he had to move.

Mr. Lu is comforted by his work documenting tens of thousands of protests, even if he can’t return to that role. “I’d just end up in jail again,” he said. “You can tell people how brave you are, but in reality you wouldn’t achieve anything.”

The Wall St Journal