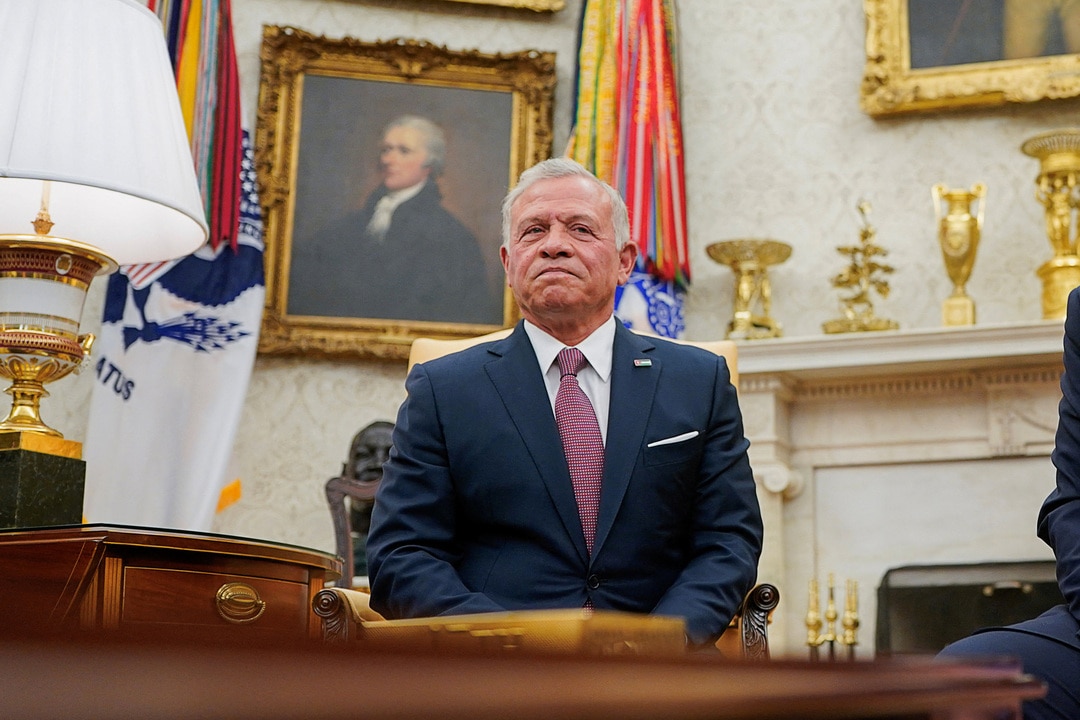

Trump tells Jordan’s King Abdullah the US will take over Gaza

Speaking at the White House with Donald Trump, King Abdullah didn’t say whether Jordan would accept Palestinians but said regional leaders were trying to work out how to make the Gaza takeover proposal work.

President Trump has said the US would take control of Gaza under its own authority – not buy it – to carry out his improbable plan to empty the territory of its nearly two million residents and relocate them permanently to Jordan, Egypt and other Middle East countries.

“There’s nothing to buy. We will have Gaza,” Trump said, sitting next to Jordan’s King Abdullah II in the Oval Office. “We are going to take it.” Asked what authority he would use to take it, he said, “United States authority.” But even as Trump portrayed his Gaza plan as virtually a done deal, his meeting with Abdullah underscored the many obstacles that remain in its way.

Abdullah repeatedly sidestepped questions about whether he would accept evacuated Palestinians, saying decisions would be made with the US after Egypt presents its own plan on Gaza’s future. Both Jordan and Egypt have previously rejected Trump’s calls to permanently remove all Palestinians from Gaza.

“I have to look into the best interests of my country,” Abdullah said. “Let’s wait until the Egyptians” can present its ideas, he said.

Trump said there was no need to threaten to withhold aid to Jordan and Egypt in order to pressure them to agree to his plan.

“We don’t have to threaten with money,” Trump said. “I think we’re above that.”

Trump’s surprise proposal – for the US to take over the Gaza Strip and develop it as an international destination while its residents are relocated – has shocked the Middle East. But he has continued to press the case, including saying in an interview aired Monday that Palestinians wouldn’t have the right to return to their homes. A key question is where the Palestinians would go, and Trump hopes one of the answers will be Jordan.

That leaves the king walking a tightrope. His country is heavily dependent on the more than $1 billion in annual aid it receives from the US, making it vulnerable to pressure from the president. But it also has to carefully balance peace with Israel and support for the US with the demands of an increasingly restive population already largely composed of Palestinians.

“Traditionally, being the first Arab visitor to the White House is an honour,” said David Schenker, who served as the top State Department official for the Middle East during Trump’s first term and is now at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “But it’s a rather unenviable position to be in right now.”

Abdullah’s tricky task will be to work with Egypt and Gulf states like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia to come up with an Arab alternative for Gaza, Schenker said: “To come in with alternatives that are both robust and will help solve what until now is a problem without a solution.”

Trump had invited Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi to meet at the White House as well. But Sisi is concerned about the optics of meeting with Trump and the risk of being cornered publicly while the US leader is pushing an idea for Gaza that is anathema to much of Egypt’s population and a security concern for its military, Egyptian officials said.

Egypt didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. It said Sunday that it would host a summit of Arab leaders later this month to discuss “the new and dangerous developments in the Palestinian issue.” The country’s foreign minister met in Washington on Monday with Secretary of State Marco Rubio and other Trump administration officials.

Trump’s persistence in calling for Palestinians to leave Gaza has surprised many in Washington. Some of Trump’s aides initially softened the idea only to see Trump reassert it even more strongly.

After Trump first broached the idea that Gazans should depart, a senior Trump administration official sought the next day to make it more palatable by saying that the Palestinians who left would be assured they could return after Gaza was rebuilt. But the president contradicted that in comments to Fox News that aired Monday.

That has raised the stakes for Abdullah. Jordan, like Egypt, has deep-seated political objections to taking in a massive population transfer of Palestinians. Jordan’s foreign minister, during the war in Gaza and well before Trump floated his proposal, said any attempt to displace Palestinians into Jordan would be treated as “a declaration of war.”

“The proposal is catastrophic,” said Oraib Rantawi, director-general of the Amman, Jordan-based Al Quds Center for Political Studies. “We cannot accept gambling with the country’s security, national identity, and very existence.” Small, resource-limited Jordan, which established formal ties with Israel in the 1990s and where millions of the Palestinian diaspora live, has long been a bastion of relative stability in a volatile region. It hosts US troops and helped Israel fend off missile attacks from Iran last year. The US agreed in 2022 to provide Jordan with about $10 billion in aid over seven years.

But a sluggish labour market, high poverty levels among refugees, low trust in public institutions and decreased US aid to agencies that assist Jordan could fan the flames of brewing political discontent.

Protests in support of the Palestinian cause have taken place frequently in the country’s capital, leading to rare open criticism of the government and its diplomatic and economic relations with Israel. Protesters have at times gathered near the US and Israeli embassies, where they clashed with Jordanian forces.

During Jordan’s last parliamentary election, in 2024, a political party affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist movement that gave rise to Hamas and is banned in many countries, captured enough votes to become the largest bloc in the House of Representatives.

Abdullah can’t afford to be seen as co-operating in an enterprise that will be portrayed in the Arab world as a betrayal of the Palestinians, particularly amid internal security concerns exacerbated by the flow of illegal weapons smuggled from Syria for years under the Assad regime.

Jordan risks again becoming a hotbed of militancy if armed Palestinian elements enter the country en masse. Abdullah’s great grandfather, King Abdullah I, was killed by a Palestinian assassin in 1951. His father, King Hussein, expelled thousands of Palestinian militants after months of brutal armed clashes between the army and the Palestine Liberation Organisation in the early 1970s.

Few Middle East experts think Trump’s plan is practical due in large part to Palestinians’ fear of being forced into a permanent exile and Jordan and Egypt’s refusal to accept them. Some have raised concerns about international law and whether it constitutes ethnic cleansing.

From Trump’s perspective, his plan has the virtue of simplicity, some of its proponents say. Not only might it make it easier to rebuild Gaza, but it also hints at a solution for the unsolved question of how to remove Hamas from the territory. Since everybody would be called on to leave the enclave, the remaining Hamas fighters and sympathisers would also depart. Later, the international community could determine who would be allowed to live in the reconstructed enclave, and Hamas would be shut out.

That suggests his idea is more than a norm-breaking scheme for how to reconstruct Gaza. Rather, it implied a new paradigm for how to deal with Palestinian aspirations. At a minimum, some of its advocates say, it will spur Arab nations to put forth a plan to deal with the security and financial challenges of rebuilding Gaza.

“Right now, the only one who’s stood up and said I’m willing to help do it is Donald Trump,” Rubio said during an interview Monday with SiriusXM Patriot. “All these other leaders, they’re going to have to step up. If they’ve got a better idea, then now is the time. Now is the time for the other governments and other powers in the region, some of these very rich countries, to basically say, OK, we’ll do it.” That has put Jordan and Egypt on the spot, current and former US officials said.

“Abdullah faces a complicated task: how to explain to Trump why Arab leaders have a problem with his call and yet also show they also understand that there must be a practical approach to reconstructing Gaza and why this can only be done with Hamas no longer in control,” Dennis Ross, who served a senior Middle East official in both Democratic and Republican administrations, said. “Striking that balance requires offering practical suggestions for how to do it and showing how it fits into Trump’s desire to expand the Abraham Accords.” The accords were brokered by the US during Trump’s first administration and normalised relations between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco – a breakthrough Trump hopes will be expanded to include normalised Israeli ties with Saudi Arabia.

Some US officials see the threat of cutting aid to Jordan as a double-edged sword. The US has economic leverage over Jordan, including substantial economic and military aid. But cutting support to Jordan could foster instability in the region.

“Even the Israelis would have to understand that cutting off the $1 billion plus to Jordan could create the kind of instability that they don’t need with their longest and arguably least defensible border,” said Aaron David Miller, a former US peace negotiator.

“The Jordanians can’t afford to walk away from Trump. The leverage is on Trump’s side. I just don’t think the king is going to agree,” said Miller. “It’s not a real-estate deal to Abdullah. It’s an existential problem.”

Dow Jones

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout