The ‘too quiet’ Russian spies who lived next door

A young foreign couple now in prison facing trial in Slovenia for espionage are alleged to have been part of Vladimir Putin’s shadow war with the West.

The young Argentine couple in the pastel-coloured house lived a seemingly ordinary suburban life, driving around this sleepy European capital in a white Kia Ceed sedan, always paying their taxes on time and never so much as getting a parking ticket.

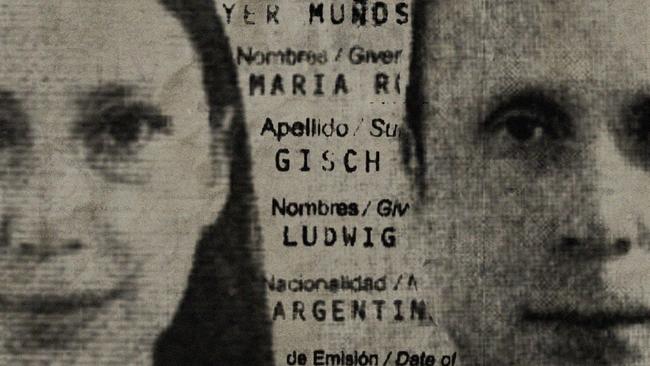

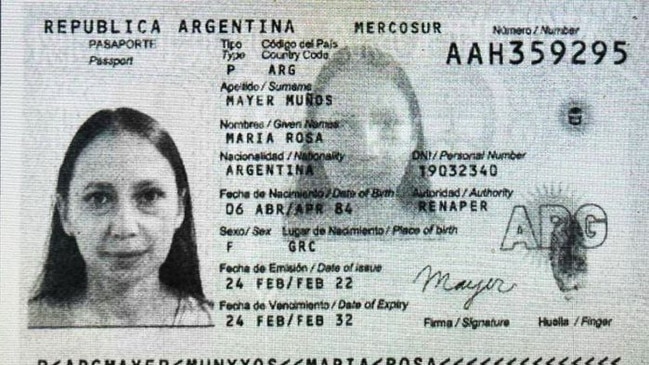

Maria Rosa Mayer Munos ran an online art gallery, telling acquaintances she’d left Argentina after being robbed in Buenos Aires by an armed gang at a red light.

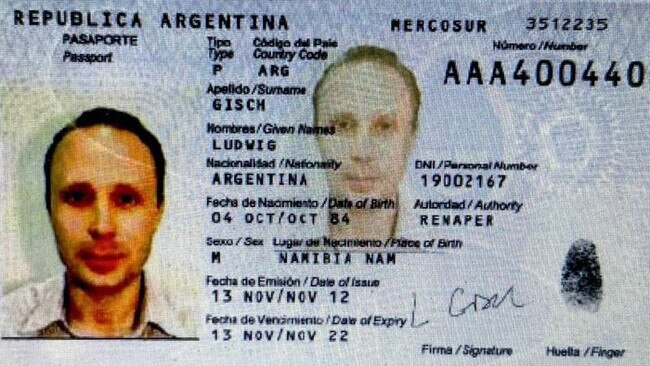

Her husband, Ludwig Gisch, ran an IT start-up.

Described by neighbours in their middle-class district of Crnuce as “normal” and “quiet”, the husband and wife appeared to be global citizens: switching from English and German with friends to accentless Spanish with their son and daughter, who attended the British International School.

Yet almost everything about the family from No 35 Primo Iceva Street was a carefully constructed lie, according to Slovenian and Western intelligence officials.

Gisch’s real name is Artem Viktorovich Dultsev, born in the Russian autonomous republic of Bashkortostan and an elite officer in Russia’s foreign intelligence service, the SVR, according to the officials and court documents.

Mayer Munos is Anna Valerevna Dultseva, a more senior SVR officer than her partner, from Nizhny Novgorod.

The couple’s computers contained hardware to communicate securely to handlers in Moscow that was so encrypted neither Slovenian nor US technicians could crack it.

In a secret compartment inside their refrigerator, they kept hundreds of thousands of euros in crisp bank notes.

Now, a classified trial is expected to deliver its first judgment in the coming weeks on the couple charged with conducting espionage as “illegals”, or deep-penetration agents – two crucial cogs in Vladimir Putin’s fast-expanding shadow war with the West.

Officials say that before they were arrested in December 2022, the pair used Slovenia, a NATO and European Union member state of just two million people, as a base to travel to nearby Italy, Croatia and across Europe to pay sources and communicate orders from Moscow. The bucolic Alpine country of lakes and mountains – and birthplace of Melania Trump – was a perfect choice to conduct operations, with visa-free access across much of Europe and a limited counterintelligence capacity.

They had even trained their two young children, Slovenian officials say, telling them that one day their mum and dad may be captured.

Shortly after Mayer Munos and Gisch were arrested in a dawn raid by Slovenia’s security services, another pair of suspected Russian illegals – a woman and man carrying Greek and Brazilian passports – abruptly left their lives in Athens and Rio de Janeiro, abandoning businesses and romantic partners who had no idea of their real identity.

The pair carried passports identifying them as Maria Tsalla and Ludwig Campos Wittich. In fact, they were married Russian intelligence officers still building out their legend – a spy’s fake background story – separately in Greece and Brazil, a process Western intelligence agencies estimate costs millions of dollars per person.

They were called back to Moscow by handlers fearing the collapse of a network after the Slovenia arrests, officials said.

Other suspected Russian illegals have been exposed across Europe since the Ukraine invasion, from The Netherlands and Norway to the Czech Republic and Bulgaria – the biggest unmasking of deep-penetration agents since the FBI’s 2010 Operation Ghost Stories that nabbed 10 Russian spies in America.

Now locked in a Slovenian prison, their children housed with a foster family, the faux-Argentine couple is also a possible component in any prisoner swaps agreed with Russia, including those that may involve jailed Americans Paul Whelan and Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, according to senior Slovenian and US officials.

The Kremlin has already expressed interest in getting them back in talks handled by Putin’s longtime close ally, Nikolai Patrushev, according to people familiar with the situation.

Neither the Kremlin nor the SVR responded to requests for comment. The case – being investigated by Slovenian and Western officials at the highest levels of secrecy, with the court proceedings and all materials highly classified – reveals a rare insight into one of the most secretive and prized parts of Russia’s spy machine.

Unlike most spies, illegals don’t pose as diplomats but usually as people unconnected to Russia. They spend years burrowing themselves deep into their target region, creating a spider web of information sources, identifying candidates for recruitment – “talent spotting” – and taking on assignments as a cutout for spies under diplomatic cover, who tend to be under close surveillance by their host countries.

Created in the early days of the Soviet Union and dramatised in the TV show The Americans, a previous generation of Russian illegals in the 1940s had played a key role in stealing American atomic secrets.

Stalin, who saw the illegals as a crucial tool for influencing the policies of adversaries and gathering intelligence on potential threats, created specialised training programs and deployed them in strategic Western capitals.

The program has been reinvigorated by Putin, who allegedly worked with illegals during his time as a KGB officer in East Germany and has sung patriotic Soviet songs with agents caught in the US and returned to Moscow in prisoner swaps. “These are special people, of special quality, of special convictions, of a special character,” he said about illegal spies in a 2017 interview with state television.

It is highly likely that Putin receives personal briefings on illegals’ exploits around the world, said Dan Hoffman, a former CIA station chief in Moscow.

In the Operation Ghost Stories case, the FBI said Russian illegals spent years establishing a seemingly normal existence in the US: They married, bought homes, raised families, and integrated into American society.

One of them studied at Harvard and another earned two masters degrees from Seton Hall University. Two others worked in real estate.

But beneath the surface, they were actively gathering intelligence and transmitting it back to Moscow, while also seeking individuals who could be recruited as future agents. One of them infiltrated a well-connected consulting firm with offices in Manhattan and Washington, DC, by working as the company’s in-house computer expert, the Journal has reported. Others were even cultivating their own American-born or -raised children as agents with even deeper cover that would be more likely to pass a US government background check.

Deep-cover agents face greater risks than embassy-based operatives who work with the protection of diplomatic immunity and are often discreetly deported if caught. Illegals are likely to be handed lengthy prison sentences, meaning a year-long wait to be released or exchanged in a prisoner swap.

These shapeshifting spies are now becoming a more important tool for the Kremlin after some 700 suspected Russian intelligence officers operating under diplomatic cover were expelled worldwide in the aftermath of the Ukraine invasion. The Czech government recently proposed that all Russian embassy workers in the EU should be restricted from moving freely inside the border-free travel zone in Europe, which would make it more difficult for spies under diplomatic cover to liaise with illegals abroad.

NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg said on Thursday that plans were being drawn up to tighten restrictions on the movement of Russian intelligence personnel in Europe.

“Illegals are again growing in significance for Moscow, especially as the line between espionage and war is becoming almost non-existent,” said Andrei Soldatov, a Russian security expert who has spent years studying Moscow’s spy networks.

Slovenian officials said that they suspect that an unusual influx of Russian students enrolling in the country’s universities in the past two years, many of whom are in their 40s and 50s, could be cover for more Russian agents. In March, the government deported at least eight Russian students for disseminating pro-Kremlin propaganda and impersonating Slovenians online, according to Slovenian security officials.

The same month a Russian military attache Sergei Lemeshev was declared persona non grata after he was discovered running a disinformation operation that involved paying “hundreds of sources” to publish pro-Moscow talking points.

To untangle the truth about the quiet couple who immersed themselves in new roles as an ordinary expat family while leading double lives as Russian spies, the Journal talked to their friends and neighbours; Slovenian, Western and Latin American officials; and reviewed hundreds of sealed documents, including birth and marriage certificates, flight records, Interpol notices and Argentine court records. Along the way reporters found a complex web of lies, from fraudulent documents to the theft of an identity of an infant who died in a small Greek village more than 30 years ago.

“We know they were important, serious agents,” said Vojko Volk, Slovenia’s state secretary for international affairs and national and international security. “It’s like The Americans, except in Slovenia.”

Building a legend

The cover story begins with a 2012 bus journey across Uruguay’s border with Argentina, where the couple began a decade-long effort to build an entirely false identity.

A cache of sealed Argentine court documents shows Gisch entering the country on a tourist visa from Uruguay and Mayer Munos arriving shortly after from Mexico. The couple then almost immediately began gathering documents – many of them fraudulent – to obtain citizenship.

Gisch claimed he was an Austrian citizen born in Namibia to an Argentine mother, which gave him a fast track to citizenship. Mayer Munos claimed she was Mexican and submitted a birth certificate saying she was born in Greece.

The couple moved to the Argentine capital and began building out their legend: living in the middle-class neighbourhood of Belgrano and attracting little attention among the 146 apartments in their building.

Mayer Munos attended a public relations class, graduating with top grades. Gisch opened accounts with Banco Galicia and Banco Macro. Neighbours and locals described them as a shy couple who didn’t attend the building’s tenant meetings. The concierge saw them come and go at routine times, with Gisch often wearing a tie. In 2012, Gish applied for Argentine citizenship, with Mayer Munos applying a year later. In 2013, the couple welcomed a daughter, Sophie.

“They were very polite, respectful,” said the owner of a nearby deli, Jamoneria del Virrey, where the couple would buy ham and cheese. “They always paid in cash.”

Mayer Munos was granted citizenship in November 2014 and a son, Daniel arrived the following August.

A month later, the couple married in their local registry office in a small ceremony witnessed by two Colombian citizens. Gisch was listed as a merchant, Mayer Muños as an events organiser.

Real identities

Slovenian officials and Argentine court and Interpol documents reviewed by the Journal show the couple’s names were Artem Dultsev and Anna Dultseva, suggesting they had married in Russia before they arrived in Argentina. Illegals are often sent abroad as couples, sometimes after an arranged marriage during their training in Russia, espionage experts say.

A year after their Argentine nuptials, an amendment was made in the marriage certificate, changing Mayer Munos’ mother’s nationality from Austrian to Mexican. The family were set to move to Europe, where background checks by Austria’s government could reveal a hole in their story.

As they prepared to leave, Gisch drained his Banco Galicia account, the final statement showing a balance of 18,784 Argentine pesos, only $US21 ($32).

The family landed in Slovenia on tourist visas in the northern summer of 2017, for the next act of their double lives, this time in the EU.

Gisch established DSM&IT, a business selling domain names and cloud hosting. The company had three followers on X, including the account of his wife’s business, Art Gallery 5’14, an online company buying and selling mostly modern art. The gallery claimed to work with 90 artists and had prolific social media accounts posting images almost daily. Gisch would ride his bike the short distance from the Crnuce neighbourhood into central Ljubljana, while his wife would drive the family car.

In 2019 they received Slovenian residence permits, putting them on a path to citizenship.

Mayer Munos was using Ljubljana as a base to travel across Europe, posting pictures of art fairs and exhibitions in places like Zagreb and Edinburgh. A photo from the 2019 Art Fair Zagreb shows her adjusting paintings next to a step ladder, her face not visible.

In 2020, the 5’14 gallery organised an online photo competition, Life in Quarantine, with a €500 ($800) cash award. None of the hundreds of photos shared on their social media accounts showed a clear picture of Mayer Munos or Gisch, but one image posted on Facebook in December 2020, the height of the pandemic, appears to be taken at the front gate of the family home, showing four face masks dangling from a washing line.

“She was always in a good mood and joyful, and had lots of fun together with other artists,” said Marko Milic, a fine art photographer from Croatia who had met Mayer Munos at a Zagreb art fair.

Both companies appeared designed to attract little attention. They were registered in a nondescript building on Ljubljana’s outskirts along with dozens of other foreign companies such as translators, accountants and financial advisers.

The couple filed annual tax returns and paid promptly, according to Slovenian corporate records. Art Gallery 5’14 claimed in 2021 to have €25,220 in revenues, while the IT company reported €43,785. Neither received public funding or had dealings with entities within tax havens, which could have raised suspicions of Slovenian authorities.

At their two-storey home, the couple spoke Spanish with their son and daughter, neighbours said. Majda Kvas, 93, said she never saw any visitors, but remembers them having at least two family picnics in the garden. “They kept to themselves,” she said. “They were quiet, they wouldn’t even say hello.” They weren’t quiet enough.

The tip-off

On February 24, 2022 – the same day that Putin began his invasion of Ukraine – the couple were back in Argentina, applying for an express processing of a new, or clean, passport, before immediately returning to Slovenia via Frankfurt.

A few months later, Slovenia’s spy agency, SOVA, or “Owl”, got a tip from an allied agency: They should look into Gisch and Mayer Munos.

Slovenia’s top security officials called allies, who began working in a multinational cell to retrace their movements in Ljubljana, Buenos Aires and across Europe. “We worked together in the utmost secrecy,” said Volk, the state secretary. “It was a puzzle.”

Investigators set up wiretaps, collecting text messages and other data from the couple, which showed them meeting sources in European countries. Slovenian officials could see their companies were fronts, financed by cash collected from their handlers and money from prepaid cards as well as transactions between the two firms to give the impression of cash flow.

In Argentina, police visited the town Gisch had listed on his passport application and found he had never lived there. At the addresses given by the Colombians who witnessed the couple’s wedding, nobody had heard of them. Slovenia requested the fingerprints of Artem Dultsev and Anna Dultseva from Interpol, then sent them to Argentina to compare with Gisch and Mayer Munos. They matched.

More concerning was that the couple had also begun spying in Slovenia: targeting the Agency for the Co-operation of Energy Regulators, or ACER, the only significant EU body based in Ljubljana which co-ordinates regulatory actions among the bloc on electricity and natural gas. The agency, whose headquarters is located around 8km from the couple’s home, raised its profile after the Ukraine invasion as energy became an especially acute topic for the continent and Russia used its gas supply to squeeze European industry. ACER didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The Slovenians and their allies realised the couple were no longer just creating their backstory. “They had been awoken,” Volk said.

On December 5, 2022, masked police in tactical gear arrived after midnight, jumped the family’s fence and positioned themselves outside the windows. When the couple raised the shutters, the officers burst in and arrested them. Gisch and Mayer Munos refused to divulge any information to the investigators after their arrest, according to a former official. Their two children – now aged 8 and 11, according to the Argentine court documents – were placed in the care of the state and moved to another school. They are allowed regular visits to their parents in prison.

Shortly after the arrest, Russia established contact, acknowledging the couple worked for the SVR and saying it wanted them back. Slovenia was eager to quickly trade and to avoid antagonising the Kremlin, but a deal couldn’t be reached. Slovenian officials had “prayed to get rid of them”, one senior official said.

Mayer Munos and Gisch refused to talk, but Slovenia and its allies were learning more about their activities and other potentially connected agents.

When Maria Tsalla fled Greece shortly after the arrests, Greek authorities discovered she had registered her birth on the island of Evia, claiming the identity of an infant who was listed as dying in 1991.

Authorities could see the handwritten registry had been altered – a clue to her deception – and that Tsalla had been trying to replace it with a new registration in the Athens suburb of Marousi, one of the first municipalities to digitise records.

Tsalla left behind a boyfriend in Athens who allegedly had no idea she wasn’t from Greece. Greek authorities discovered she was in fact married to another Russian illegal, Campos Wittich, who had lived for some two years in Rio de Janeiro with his Brazilian girlfriend – a veterinarian who worked for the country’s Ministry of Agriculture.

She helped co-ordinate the social media search for him when he disappeared – only to learn that he was working undercover for Russian intelligence.

Gisch and Mayer Munos have now served more than 18 months in a Slovenian prison. Slovenia’s espionage laws allow for a maximum eight-year sentence, and officials say the couple could be freed after four for good behaviour.

“They were long-term illegals,” said Janez Stusek, SOVA chief until the middle of 2022, several months before the couple’s arrest. “They had a long-term mission trying to infiltrate Slovenia as an entering point into Europe.”

On 35 Primo Iceva Street, a new couple has moved in. Two bikes are parked on the porch and two children’s badminton rackets are hung on the veranda. Efforts to reach them were unsuccessful, and the owners of the house declined to comment. The new couple, officials and neighbours said, are also Russian.

Novica Mihajlovic and Yannis Palaiologos contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout