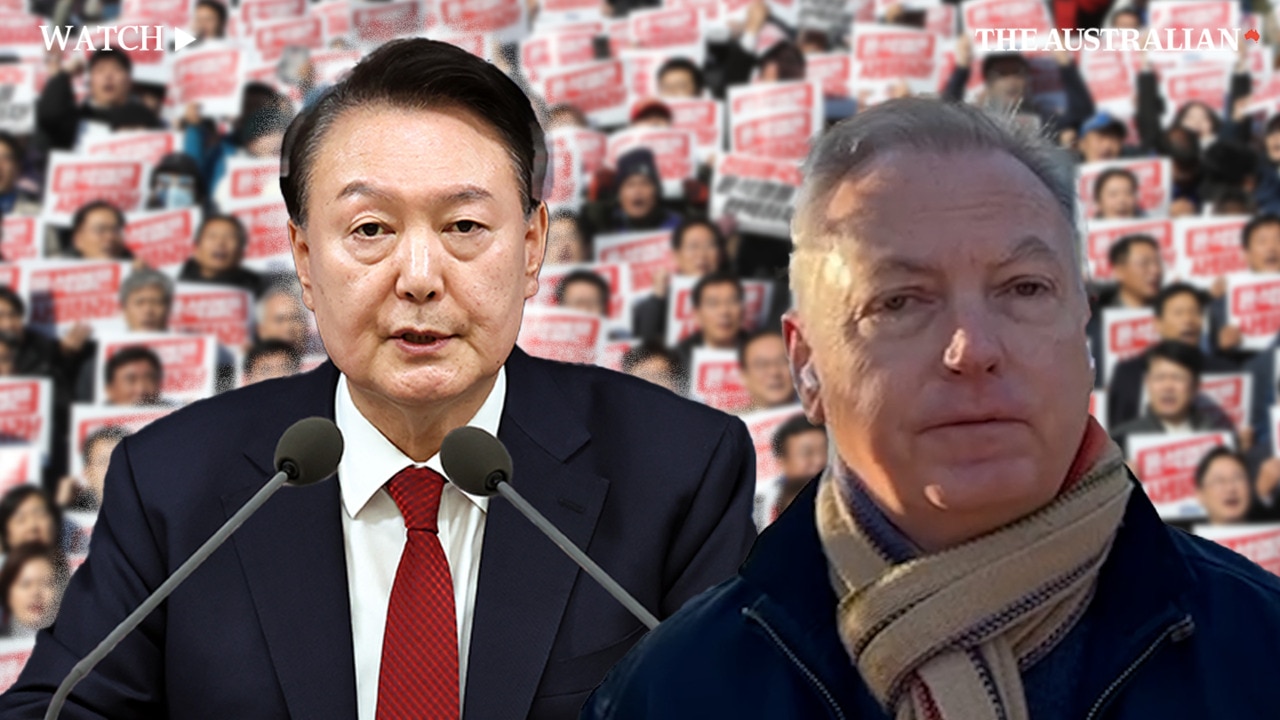

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol faces impeachment motion after declaring martial law

A day after declaring martial law, Yoon Suk Yeol is now facing the prospect of impeachment, creating more political instability for the close US ally.

A day after declaring martial law, South Korea’s president is now facing the prospect of impeachment, creating more political instability for a close US ally.

South Korea’s Parliament has submitted a motion to vote on removing the conservative Yoon Suk Yeol by Friday or Saturday, opposition lawmakers said. To do so, they will need a two-thirds backing at the country’s unicameral, 300-seat National Assembly.

The main opposition Democratic Party, along with its allies, have at least 191 seats under their control. That means a handful of lawmakers from Yoon’s ruling People Power Party will need to be persuaded to break ranks.

Yoon’s move to declare martial law late Tuesday night stunned South Korea’s political establishment and caught U.S. officials by surprise. Within about six hours, Yoon reversed course after lawmakers voted 190-0 against the measure, a group that included nearly 20 lawmakers from Yoon’s own party.

For several hours from late Tuesday to early Wednesday, Yoon exercised a type of military control over South Korea that had been avoided for more than four decades. Armed soldiers broke windows and stormed into the National Assembly building. The government gave itself jurisdiction over the country’s military, political activities and medical staffing.

Yoon has seen his approval ratings fall to new lows and has described his political opponents as antistate forces. In calling for martial law, Yoon said disputes over budget talks and investigations of top prosecutors had set the country into a constitutional crisis and left it vulnerable to North Korean “communist forces.” The fallout on Wednesday was broad. South Korea abruptly canceled a state visit by Sweden’s prime minister, while other top officials scrapped public meetings. Amid the political upheaval, Washington and Seoul are postponing several coming bilateral meetings, including one joint group that focuses on nuclear issues as well as a related tabletop military exercise.

Meanwhile, Yoon’s defense minister, chief of staff and other senior aides tendered their resignation. South Korea’s government promised “unlimited” liquidity to keep its financial markets stable. South Korea’s largest labor union with more than 1 million members vowed to remain on an indefinite strike until Yoon steps down. Cities around the nation planned candlelight rallies.

‘Changes so slowly’ Just hours after Yoon lifted martial law, Sung Gi-bong headed to Gwanghwamun Plaza in central Seoul, an iconic site for the country’s transition to democratization in the 1980s. Back then, Sung was a college activist, who saw other young protesters die while clashing with the military police. He wanted to express discontent over Yoon’s attempt to deploy the type of military control that summoned painful memories of the past.

“It’s frustrating that the world changes so slowly,” said Sung, who is now 58 years old. “But I think it will thanks to the many people who try.” If the upcoming National Assembly impeachment vote passes, Yoon’s presidential powers would be revoked immediately. The country’s prime minister, Han Duck-soo, would temporarily assume control in the meantime.

Yoon’s potential ouster from office would still require a subsequent two-thirds vote by South Korea’s constitutional court, which rules on the legal merits of the impeachment. Currently, the nine-judge court has three vacant seats, owing to political disputes over the nominees. It’s not clear if an incomplete court could proceed.

It took about six months, from impeachment to new leader, the last time a South Korean president was removed from office.

That occurred when former President Park Geun-hye was impeached in December 2016 over an influence-peddling scandal. Three months later, the constitutional court, by a unanimous vote, upheld the impeachment and ousted her from office. A snap election for the country’s next leader took place two months later.

The 63-year-old Yoon, who rose to national fame as a prosecutor, worked on the case that put Park behind bars. Now he is the target for an early dismissal. He is about halfway through his single five-year term that ends in 2027. By law, Yoon cannot run for reelection.

“It has become clear to the entire nation that President Yoon can no longer conduct state affairs normally,” said Lee Jae-myung, who heads the opposition Democratic Party, and would be considered a frontrunner should South Korea soon hold a presidential election.

Legal questions Now, Yoon’s fate hinges on a legal question: Was his move to enact martial law justified? Not long after Yoon’s televised speech announcing the move, both major political parties called the act illegal.

Under South Korea’s constitution, martial rule is reserved for times of war or similar national emergencies where public safety is threatened. To declare martial law, the country’s president must convene a cabinet meeting in advance and inform the legislature.

It’s not clear if Yoon’s rationale, centered on risks created by his political opponents, would fit the constitutional threshold or if he followed the proper procedures, said Shin Yul, a political science professor at South Korea’s Myongji University.

“If any of these conditions were not met, then it is a serious constitutional breach and a cause for potential impeachment,” Shin said.

Kim Jong-eun, a 44-year-old doctor in Seoul, was among those looking for change at the top. She said a president shouldn’t threaten the public and expects Yoon to be impeached. “What must be corrected,” Dr. Kim said, “must be corrected.” Yoon’s popularity has fallen over a string of scandals, unpopular appointments and a lack of popular policies. His successes have occurred in foreign policy, such as belting out “American Pie” at the White House or meeting President Biden and his Japanese counterpart at Camp David. His approval ratings recently dipped below 20%.

The move to assert military rule is going to weaken Yoon further given the pride South Koreans have in the country’s democracy, said Ji-Young Lee, a professor at American University in Washington D.C., who focuses on East Asia security.

“Everyday, South Koreans see no reason that would justify his declaration of martial law,” she said.

Soobin Kim and Dasl Yoon contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout