Benedict stood firm against threat to West’s values

A big story this past year has been the firming alliance between the world’s two leading autocrats, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping, predicated on their conclusion that the West is in terminal decline.

Fortuitously, the world has just lost its most relevant analyst of the presumption that the West is finished – Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

It would be insulting to the seriousness of Benedict’s criticism of Western culture to say he shared the views of Putin and Xi, whose ideas about the West’s moral decline merely support strategies of cynical opportunism.

Russian bots feed destructive garbage into the West’s social media ecosystem, which is also the reason US national security specialists – like many parents – believe the TikTok platform is being used by China’s leadership as a force multiplier of cultural erosion.

Benedict, by contrast, desperately wanted to save the West and the Judaeo-Christian tradition to which he had devoted his life.

It may seem quixotic to enlist a deceased pope for the competition with China and Russia. Benedict’s immediate predecessor and good friend, Pope John Paul II, had Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and a small army of pro-Western intellectuals as allies in his battle with the ideology of Soviet communism. Their only like today is Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky.

Moreover, the challenge from China and Russia is discussed mostly in military and economic terms. Ukraine’s defence against the Putin invasion is about transfers of military hardware and economic sanctions on Russia. Despite a new consensus that Xi has made China an aggressor nation, most thinking is about economic disentanglement and funding a long-delayed defence in the Pacific region.

But this underestimates the stakes as Putin and Xi see them. For them, this project isn’t only about specialists analysing military and economic capacities. It’s about fundamental belief systems. As such, this is likely to be a long-term struggle that runs beyond the battles over Ukraine or Taiwan.

Their conclusion is that the West’s populations have become morally soft and politically disconnected from any firm belief in the liberal democratic values that won two world wars and helped the West rise to economic and cultural dominance. Putin and Xi think the Western belief system is vulnerable now and replaceable.

“The moral, historical truth is on our side,” Putin said in his New Year’s address. “This is the year”, he said, that “showed that there is no higher power than love for one’s family and friends, loyalty to friends and comrades-in-arms, and devotion to one’s motherland”. Putin’s traditionalism, of course, is meretricious. It’s about power.

At the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th national congress in October, Xi asserted that “scientific socialism is brimming with renewed vitality in 21st-century China. Chinese modernisation offers humanity a new choice for achieving modernisation.” That new choice, evident from Chinese daily life, includes each person’s willingness to surrender to the state an array of long-assumed freedoms – of opinion, speech and privacy.

Whether Russia and China will win this competition is debatable. What’s not disputable is their belief that they have the will to displace the West’s values with their own.

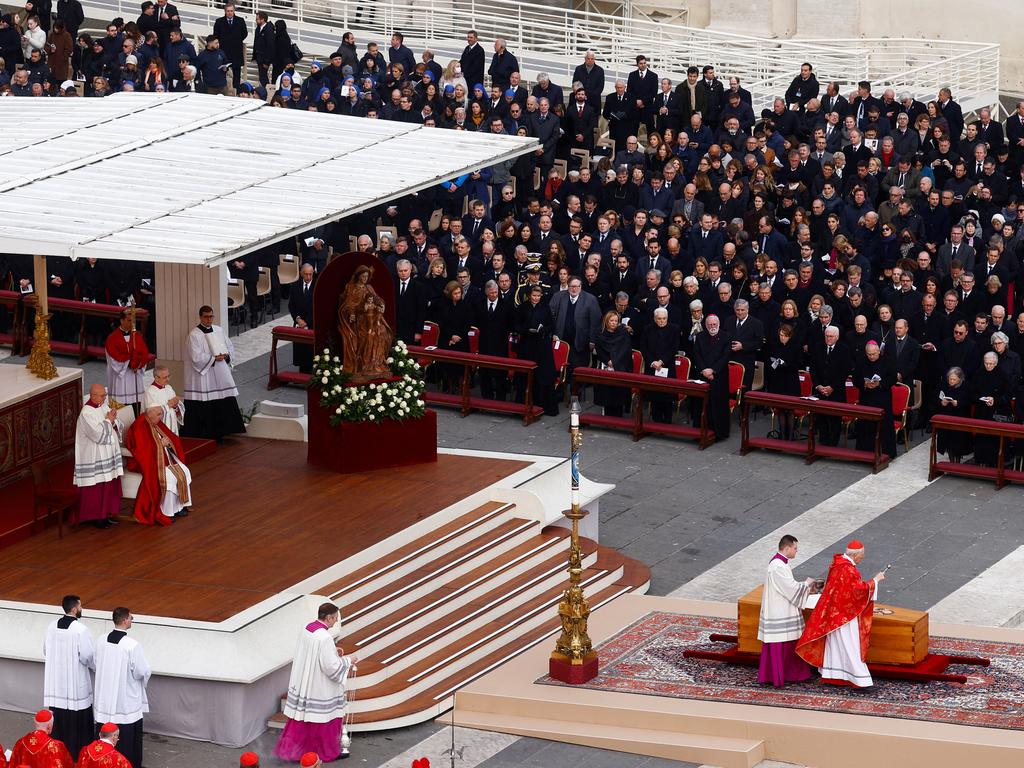

As pope, Benedict was acutely aware of China’s threat to these values. Speaking on Christmas Eve 2010 from his window on St. Peter’s Square, Benedict urged the “faithful of the church in mainland China” not to “lose heart through the limitations imposed on their freedom of religion and conscience”.

Obituaries of Benedict, while respectful, have nonetheless characterised him repeatedly as a “conservative”, which at best consigns him to just another voice in the political tumult. This is a disservice to Benedict’s intentions.

As a German cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger argued that by itself secularism, or reason, was inadequate to sustain intact social structures. He summarised these views as pope in his 2009 encyclical letter, Caritas in Veritate (Love in Truth): “Reason and faith can come to each other’s assistance. Only together will they save man. Entranced by an exclusive reliance on technology, reason without faith is doomed to flounder in an illusion of its own omnipotence. Faith without reason risks being cut off from everyday life.”

Putin and Xi want to wear us down from the outside in. But one may also ask, why should we do it to ourselves? Look at the internal destabilisation under way from social pathologies and disconnectedness. Secularism by itself provides no brake on bad choices.

This writer’s longstanding solution to reducing the country’s problems has been: go to church on the weekend. Learn that in fact you’re not No.1 and not alone.

It has become unfashionable, if not forbidden, to talk about religious belief in the context of public life. The “religious right” and all that. But perhaps the moment is right to revive Benedict’s argument for religion’s proper role in organising a coherent, self-confident society, or nation.

Daniel Henninger is a columnist with The Wall Street Journal.