In previous times, when popes and kings fell sick, followers would gather at churches and public places to pray for his recovery or, failing that, the smooth passage of his soul to a better place.

The secular equivalent today is a TV studio or social-media feed brimming with a white-coated army of attention-hungry physicians, academics and sundry experts, all apparently skilled enough to offer confident long-distance consultations about a patient they’ve never met.

Of course the patient being President Trump, the medical observations are especially dire and, at the same time, especially critical. Since the president fell ill late last week, roughly half the commentator class seems to be angry that he got sick and half angry that he hasn’t died yet. Consistency not being widely observed in the news business these days, there’s been significant overlap between the two. From their vantage point on the West Coast or at Rockefeller Centre, experts have gravely informed us that the president’s pallor, the timeline of his infection and the regimen of drugs he’s on all mean he’s got an especially serious case of Covid-19. I read and saw several this weekend who put his chances of survival at not much better than 2 in 3, even as he was evidently up and about and not on his last legs.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 5, 2020

These pathological limelight-seekers all agree that the etiology of the affliction is simple: the patient’s gross recklessness and irresponsible behaviour. He’s to blame for his own malady and for those of millions of others. His sickness is condign affirmation of his manifold failures, arrogance and incompetence. I hope to God these people don’t treat their regular patients like that. Nurse Ratched will see you now.

It’s easy to be cynical about this latest outbreak of media hysteria and bile. It would almost be comforting to think that it’s all their fault. But the White House itself carries much of the blame for this rancid atmosphere of mistrust and misdirection.

The bizarre standoff outside Walter Reed Medical Center between the White House and its press tormentors served as a brief, depressing theatrical summary of four years of this presidency.

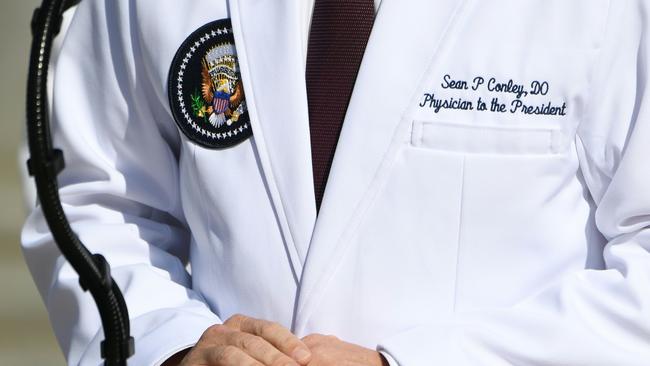

First Sean Conley, the president’s physician, gave his sunny version of the president’s health on Saturday. He was almost immediately contradicted in the most transparent off-the-record briefing by Mark Meadows, the White House chief of staff. If you wanted an allegorical picture of the Trump presidency, here it was: evasion and prevarication followed by an unverifiable half-truth mumbled into a reporter’s ear.

This Trumpian allegory continued the next day when Dr. Conley tried to explain his misdirection with a novel bit of science: “I didn’t want to give any information that might steer the course of illness in another direction.” Who knew? A virus in the body responds to words spoken at a press briefing. This sounds important.

If you had wanted to feed a hostile media’s suspicion and hostility, you couldn’t have done a better job.

The episode was as revealing as much for its ineptitude as its effort at deception. I always thought the depiction of this presidency as a mortal threat to American democracy and constitutional government was a fanciful absurdity. There’s always been more of a Keystone Kops than a Kremlin quality to Mr Trump’s methods. And it’s all so unnecessary. The president, it seems, is already on his way to recovery.

Even so, this low, depressing spectacle — a media ever more eager to peddle unsubstantiated information of the most negative sort in pursuit of an ideological agenda, and a political class feeding dishonesty to its own partisans — is the larger allegory of modern democracy on display. It points to a much deeper sickness in American politics and culture. The level of mutual mistrust — between the government and the media, between partisans of one stripe and another — is like a cancer, steadily eating away at the vital organs of the republic. Societies can’t function without a broad base of trust, a willingness to believe things one can’t prove; an acceptance of the reality of things one might not want to hear.

Unlike those physicians pronouncing their diagnoses from thousands of miles away, I can’t state with confidence the immediate prognosis for this cultural and political affliction.

But you don’t need to be a medical expert to fear that, if some kind of remedy isn’t found soon, it’s looking terminal.

Our modern media culture presents few less edifying spectacles than that of a stadium-sized crowd of animated journalists, commentators and pundits speculating on demand on the state of a man’s health.