New thinking on Covid lockdowns: they’re overly blunt and costly

Blanket business shutdowns led to a deep recession. Economists and health experts say there may be a better way.

In response to the novel and deadly coronavirus, many governments deployed draconian tactics never used in modern times: severe and broad restrictions on daily activity that helped send the world into its deepest peacetime slump since the Great Depression.

The equivalent of 400 million jobs have been lost worldwide, 13 million in the US alone. Global output is on track to fall 5 per cent this year, far worse than during the financial crisis, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Despite this steep price, few policy makers felt they had a choice, seeing the economic crisis as a side effect of the health crisis. They ordered non-essential businesses closed and told people to stay home, all without the extensive analysis of benefits and risks that usually precedes a new medical treatment.

There wasn’t time to gather that sort of evidence: Faced with a poorly understood and rapidly spreading pathogen, they prioritised saving lives.

Five months later, the evidence suggests lockdowns were an overly blunt and economically costly tool. They are politically difficult to keep in place for long enough to stamp out the virus. The evidence also points to alternative strategies that could slow the spread of the epidemic at much less cost. As cases flare up throughout the US, some experts are urging policy makers to pursue these more targeted restrictions and interventions rather than another crippling round of lockdowns.

“We’re on the cusp of an economic catastrophe,” said James Stock, a Harvard University economist who, with Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina and others, is modelling how to avoid a surge in deaths without a deeply damaging lockdown. “We can avoid the worst of that catastrophe by being disciplined,” Mr Stock said.

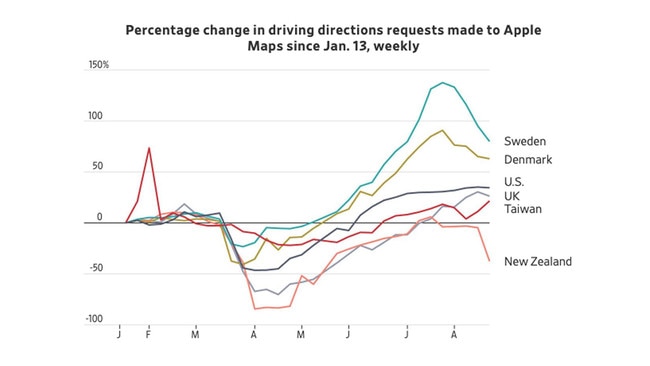

The economic pain from pandemics mostly comes not from sick people but from healthy people trying not to get sick: consumers and workers who stay home, and businesses that rearrange or suspend production. A lot of this is voluntary, so some economic hit is inevitable whether or not governments impose restrictions.

Disentangling voluntary and government-ordered effects is hard. One study, by economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson at the University of Chicago, says government restrictions account for just 12 per cent of the decline in consumer mobility in the US; another, by a team led by economists Kosali Simon at Indiana University and Bruce Weinberg at Ohio State, says they account for 60 per cent of the loss of employment.

Still, because of the close connection between the pandemic and economic activity, many epidemiologists and economists say the economy can’t recover while the virus is out of control. “The virus is going to determine when we can safely reopen,” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in April. The Federal Reserve said in late July that “the path of the economy will depend significantly on the course of the virus.”

Such statements leave wide open what represents an acceptable level of infection, which in turn determines what restrictions to impose. If the only acceptable level of infection were zero, lockdowns would have to be severe and potentially repeated, or at least until an effective vaccine or treatment comes along. Most countries have rejected that course.

Prior to COVID-19, lockdowns weren’t part of the standard epidemic tool kit, which was primarily designed with flu in mind.

During the 1918-1919 flu pandemic, some American cities closed schools, churches and theatres, banned large gatherings and funerals and restricted store hours. But none imposed stay-at-home orders or closed all non-essential businesses. No such measures were imposed during the 1957 flu pandemic, the next-deadliest one; even schools stayed open.

Lockdowns weren’t part of the contemporary playbook, either. Canada’s pandemic guidelines concluded that restrictions on movement were “impractical, if not impossible.” The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2017 community mitigation guidelines for pandemic flu, didn’t recommend stay-at-home orders or closing non-essential businesses even for a flu as severe as the one a century ago.

So when China locked down Wuhan and surrounding Hubei province in January, and Italy imposed blanket stay-at-home orders in March, many epidemiologists elsewhere thought the steps were unnecessarily harmful and potentially ineffective.

By late March, they had changed their minds. The sight of hospitals in Italy overwhelmed with dying patients shocked people in other countries. COVID-19 was much deadlier than flu, it was able to spread asymptomatically, and it had no vaccine or effective therapy.

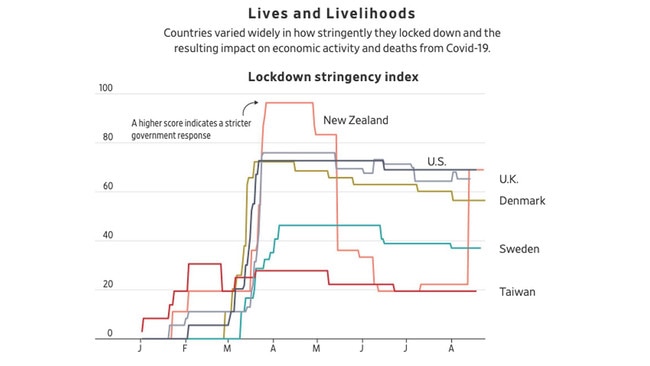

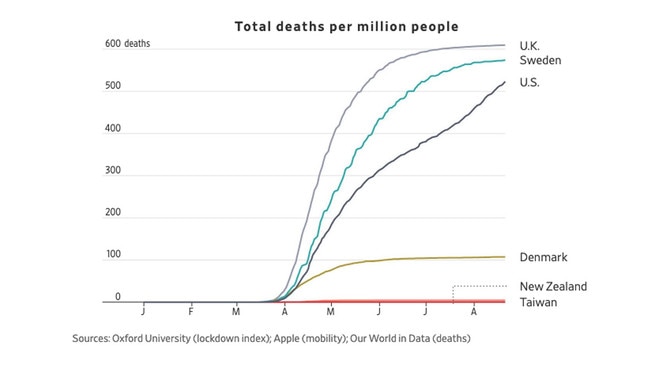

Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong set early examples of how to stop COVID-19 without lockdowns. Their reflexes trained by SARS in 2003, MERS and avian flu, they quickly cut travel to China, introduced widespread testing to isolate the infected and traced contacts. Their populations quickly donned face masks.

Sweden took a different approach. Instead of lockdowns, it imposed only modest restrictions to keep cases at levels its hospitals could handle.

Sweden has suffered more deaths per capita than neighbouring Denmark but fewer than Britain, and it has paid less of an economic price than either, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Sweden’s current infection and death rates are as low as the rest of Europe’s, suggesting to some experts the country may be approaching herd immunity. That is the point at which enough of the population is immune, due to prior exposure or vaccination, so that person-to-person transmission declines and the epidemic dies out.

By March, it was too late for the US to emulate the test-and-trace strategy of east Asia. The CDC had botched the initial development and distribution of tests, and limited testing capacity meant countless infections went undetected for months. US President Donald Trump continued to downplay testing, and even today the US conducts fewer than 20 tests for every confirmed case, compared with more than 500 in Taiwan and South Korea at their peaks.

The Swedish strategy was also taken off the table. Britain ditched it in mid-March after a team of experts from London’s Imperial College predicted that in the absence of social distancing, 81 per cent of the population would eventually be infected, while 510,000 people would die in Britain and 2.2 million in the US.

Those estimates may have been high. Some experts think it takes less than 81 per cent of a population to reach herd immunity. Nonetheless, such predictions helped persuade leaders in Britain and the US to lock down.

Yet at the outset, their goals were unclear, a confusion aggravated by the multitude of terms used. Officials sometimes said their goal was “bending” or “flattening the curve,” which originally meant spreading infections over time so the daily peak never overwhelmed hospitals. At other times they described their aims as “mitigation” or “containment” or “suppression,” often interchangeably.

“There have been few attempts to truly define the goal, and partly it’s because policy makers and epidemiologists haven’t thought well enough about the vocabulary to define what they mean or want,” said Dr Mina, the Harvard epidemiologist.

A key determinant in an epidemic’s spread is the reproduction number, or “R value”: how many people each infected person goes on to infect. When R is above one, new infections continue until enough of the population has been infected or vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. When R is below one, new infections eventually fall to zero, although imported infections can trigger outbreaks. Dr Mina said mitigation generally aims for an R of just above one, while suppression aims for an R of below one.

The US never resolved “whether we were going for mitigation or suppression,” said Paul Romer, a Nobel laureate economist. Mitigation, he said, meant accepting hundreds of thousands of additional deaths to achieve herd immunity, which no leaders were willing to embrace. But total suppression of the disease “doesn’t make sense unless you’re going to stick with it as long as it takes.”

Some countries did achieve suppression through lockdowns. China wiped out the epidemic in Hubei province and has suppressed subsequent outbreaks elsewhere, with sweeping quarantine and surveillance methods that are difficult to replicate in Western democracies.

New Zealand imposed one of the most stringent lockdowns for two months. The country — relatively small and geographically isolated — went on to enjoy 102 days without a new case. Nonetheless, an outbreak this month prompted a reimposition of widespread restrictions.

The US for the most part lacked China’s authoritarian bent and New Zealand’s patience. Asked in March if lockdowns would last months, President Trump replied: “I hope it disappears faster than that.” Indeed, at the end of March his health advisers suggested one more month of restrictions would be enough.

In mid-April, his health advisers issued guidelines for when states with lockdowns should reopen, including 14 days of declining cases and the ability to test and trace anyone with flulike symptoms. “The predominant and completely driving element that we put into this was the safety and the health of the American public,” Dr Fauci told reporters.

But that same day Mr Trump made it clear his priority was the economy: “A prolonged lockdown combined with a forced economic depression would inflict an immense and wide-ranging toll on public health,” he said. Within weeks he was praising states that had reopened despite not meeting the guidelines and was tweeting “LIBERATE” to supporters protesting lockdowns.

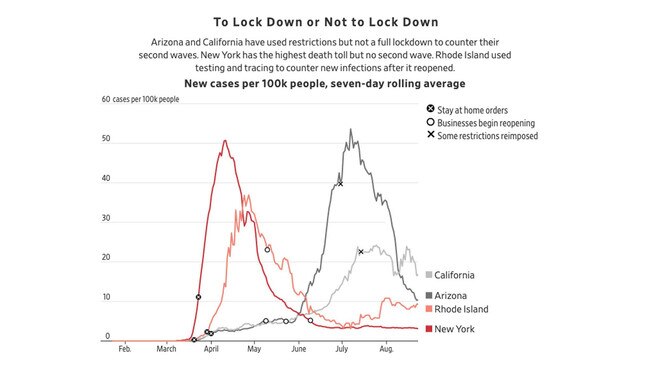

Many Republican governors prioritised their economies, but some Democrats more committed to lockdowns also struggled to stay the course. When California became the first state to issue a stay-at-home order on March 19, its Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, said the goal was to “bend the curve”.

On May 7, he signalled an unusually ambitious goal: Only counties with zero deaths in the past two weeks and no more than one case per 10,000 residents could reopen ahead of schedule — criteria that 95 per cent of the state couldn’t meet, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Mr Newsom said science and data would dictate when the stay-at-home order was lifted. Economic and social pressures soon intruded, as county leaders pushed him to relax the criteria. On May 18 he did, dropping the no-death requirement and raising the case cut-off to 25 per 100,000.

Counties quickly began opening. A month later, California’s cases began surging again, far surpassing previous highs.

“I wouldn’t say our strategy ever really changed,” said Mark Ghaly, the state’s secretary of health and human services. “We needed to get [infections] low enough to where our systems can handle sick people.”

Dr Ghaly said “there were conversations” about pursuing total suppression, as New Zealand had done, but that would have required an early, nationwide commitment, which wasn’t possible with very different views across the country.

The impact of lockdowns on families, the economy and mental health also mattered, he said: “When you see unemployment numbers going through the roof, businesses not just threatened week to week but potentially [never] being open again, you have to take that into account,” said Dr Ghaly.

Dr Mina of Harvard said the US at the outset could have chosen to prioritise the economy, as Sweden did, and accept the deaths, or it could have chosen to fully prioritise health by staying locked down until new infections were so low that testing and tracing could control new outbreaks, as some northeastern states such as Rhode Island did.

Most of the US did neither. The result was “a complete disaster. We’re harming the economy, waffling back and forth between what is right, what is wrong with a slow drift of companies closing their doors for good,” Dr Mina said.

The experience of the past five months suggests the need for an alternative: Rather than lockdowns, using only those measures proven to maximise lives saved while minimising economic and social disruption. “Emphasise the reopening of the highest economic benefit, lowest risk endeavours,” said Dr Mina.

Social distancing policies, for instance, can take into account widely varying risks by age. The virus is especially deadly for the elderly. Nursing homes account for 0.6 per cent of the population but 45 per cent of Covid fatalities, says the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a conservative-leaning think tank. Better isolating those residents would have saved many lives at little economic cost, it says.

By contrast, fewer children have died this year from COVID-19 than from flu. And studies in Sweden, where most schools stayed open, and the Netherlands, where they reopened in May, found teachers at no greater risk than the overall population. This suggests reopening schools outside of hot spots, with protective measures, shouldn’t worsen the epidemic, while alleviating the toll on working parents and on children.

If schools don’t reopen until next January, McKinsey & Co. estimates, low-income children will have lost a year of education, which it says translates into 4 per cent lower lifetime earnings.

Research by Dr Mina and others has shown that “superspreader” events contribute disproportionately to infections, in particular dense indoor gatherings with talking, singing and shouting, such as at weddings, sporting events, religious services, nightclubs and bars.

Bars and restaurants accounted for 16 per cent of COVID-19 clusters (five or more cases) in Japan; workplaces, just 11 per cent. Bars, restaurants and casinos accounted for 32 per cent of infections traced to multiple-case outbreaks in Louisiana.

Masks may be the most cost-effective intervention of all. Both the World Health Organisation and the US Surgeon General discouraged their use for months despite prior CDC guidance that they could limit the spread of flu by preventing the wearer from transmitting the disease.

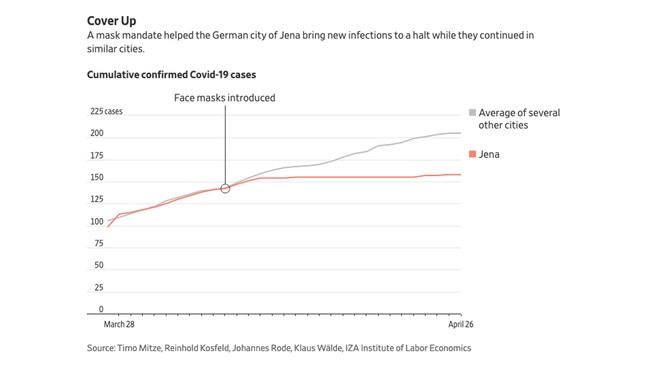

The German city of Jena in early April ordered residents to wear masks in public places, public transit and at work. Soon afterward, infections came to a halt. Comparing it to similar cities, a study for the IZA Institute of Labor Economics estimated masks reduced the growth of infections by 40 per cent to 60 per cent.

Klaus Wälde, one of the authors, said nationwide mask wearing is helping the German economy return to normal while keeping infections low. Goldman Sachs Group estimates a universal mask mandate in the US could now save 5 per cent of gross domestic product by substituting for more onerous lockdowns.

Some epidemiologists and economists argue ramped-up testing could enable the economy to reopen safely without a vaccine. Mr Romer estimates the US could restore $1000 in economic activity for every $10 spent on tests.

Dr Mina pointed to a paper-strip test anyone can use to detect the virus in a sample of saliva in minutes. It is less accurate but far faster and cheaper than sending samples to labs, he said. If 50 per cent to 60 per cent of the population in hot spots took such a test every other day, the disease could be suppressed, he said.

Dr Mina’s and Mr Stock’s team has designed a “smart” reopening plan based on contact frequency and vulnerability of five demographic groups and 66 economic sectors. It assumes most businesses reopen using industry guidelines on physical distancing, hygiene and working from home; schools reopen; masks are required; and churches, indoor sports venues and bars stay closed.

They estimated in June that this would result in 335,000 fewer US deaths by the end of this year than if all restrictions were immediately lifted. But they say the plan also would leave economic output 10 per cent higher than if a second round of lockdowns were imposed.

“If you use all these measures, it leaves lots of room for the economy to reopen with a very small number of deaths,” Mr Stock said. “Economic shutdowns are a blunt and very costly tool.”

The US South and Southwest have provided some real-time experiments in targeted lockdowns. Arizona imposed a stay-at-home order in March and rescinded it in early May.

When cases soared, Republican Govenor Douglas Ducey resisted reimposing restrictions or requiring masks. He then eventually allowed cities to require masks, ordered bars, gyms, movie theatres and water parks to close and told restaurants to operate at no more than 50 per cent capacity. Gatherings of more than 50 people were prohibited and masks strongly encouraged. But he didn’t lock down the entire state. Cases and hospitalisation have since fallen sharply to early May levels, or lower.

California, similarly, ordered indoor activities at restaurants, bars, museums, zoos and movie theatres to close in mid-July, but didn’t issue a stay-at-home order, prohibit outdoor activities or suspend elective surgery, as it had in March and April. Cases have begun to drop, while hospitalisation have declined 35 per cent since their July peak.

“In March, people didn’t realise the benefits of mask use,” said Dr Ghaly, the state’s secretary of health and human services. “The evidence on being outdoors rather than indoors is quite compelling.” Compared to April, “We know so much more.”

—Graphics by Hanna Sender

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout