China’s CDC, built to stop pandemics, stumbled when it mattered most

The CDC set up to detect epidemics was in the dark about virus until December. That wasn’t how it was supposed to work.

Before going to bed, George Gao, the head of the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, typically completes his 10,000 steps for the day and then checks the news online.

When he scanned his feed on Dec. 30, he was stunned. Two leaked local-government notices warned about cases of unexplained pneumonia in the Chinese megacity of Wuhan. It was the first he’d heard of the outbreak, according to people close to him.

The 58-year-old virologist called the head of Wuhan’s disease-control office, who confirmed the outbreak and revealed to Dr. Gao’s growing alarm that it had been going on since at least December 1, with 25 suspected cases so far, the people close to him said.

This wasn’t how things were supposed to work.

Dr. Gao’s agency, known as the China CDC, was set up in 2002 precisely to detect and stop epidemics that often emerge from southern China. It was a mission that grew more urgent after a deadly outbreak that year of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS.

The China CDC trained hundreds of its staff in outbreak-response techniques with U.S. help, sent teams to fight Ebola in Africa and introduced a China-wide, real-time reporting system for infectious diseases. In Dr. Gao, they recruited an expert with credentials from Oxford and Harvard universities.

“I can very confidently say there won’t be another ‘SARS incident,’ ” Dr. Gao said in a speech last year. “Because our country’s infectious-disease surveillance network is very well-established, when a virus comes, we can stop it.”

Failed at the outset

When the virus did come, though, Dr. Gao’s agency failed at the outset. Instead of the China CDC spotting the outbreak in early December and leading a co-ordinated response, the virus was rampant in Wuhan by the time Dr. Gao learned of it. By January 23 — when authorities ordered the city locked down — it was spreading across the world.

The pathogen would go on to infect more than 21 million people by mid-August, kill more than 760,000, cause trillions of dollars of economic damage and plunge China-U. S. relations into a crisis redolent of the Cold War.

Precisely what impact earlier Chinese action might have had is hard to say. One study by scientists in China, Britain and the U.S. estimated that if control measures had begun three weeks earlier, there would have been 95 per cent fewer cases in China. Two weeks earlier: 86% fewer cases, the study found. One week earlier: 66 per cent fewer.

China has rejected criticism of its response, especially from the US, and increasingly portrays its success in taming the virus within its borders as a vindication of President Xi Jinping’s autocratic leadership style.

“The Chinese government didn’t delay or hide anything,” Ma Xiaowei, the head of the National Health Commission told a news conference in June.

Neither the China CDC, nor the commission — a cabinet-level agency overseeing the China CDC — responded to requests for comment. Dr. Gao declined to comment.

Hiding the bad news

In interviews with Chinese doctors, officials and health experts; and foreign scientists and officials who have worked with China on disease control, The Wall Street Journal found:

— The China CDC missed early signals because hospitals didn’t enter details in its real-time system, the technological core of its disease-surveillance efforts.

— The agency was outflanked by local authorities intent on hiding bad news from China’s leader and elevating Wuhan’s national political status.

— National officials delayed the response by forbidding publication of any research on the virus without approval, and shared critical information with the outside world in early January only after unauthorised leaks forced their hand.

— Financial and personnel problems hobbled the China CDC, which struggled to recruit and retain talented staff — a problem exacerbated by a withdrawal of U.S. funding and training support beginning in 2018.

That China responded to the novel coronavirus faster than it did to SARS is beyond doubt, as is its ultimate success in controlling the virus at home and the failure of the U.S. and other governments to do so.

What concerns Chinese doctors and their foreign peers is that Beijing may be no better prepared for the next potential pandemic.

“The status of the CDC should change,” Dr. Zhong Nanshan, a senior Chinese government medical adviser who played a decisive role in tackling both SARS and the new coronavirus, told a news conference in February. “If it doesn’t after this, the same situation could arise again.”

What hampered the CDC

When the China CDC was launched, its aim was to replicate the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, then the gold standard, in building state-of-the-art laboratories and data analytics and training an elite workforce to control epidemics.

Within a few months, China was engulfed by SARS, which killed 774 people worldwide. In 2004, the first China CDC chief resigned over another small SARS outbreak blamed on China CDC staff experimenting on the coronavirus that causes the illness.

The China CDC was hampered by its lack of authority within a healthcare bureaucracy whose approach to disease control was based on an antiquated Soviet model.

As one of many “technical agencies” under the NHC, the China CDC was authorised to conduct research, give advice, provide training and take the lead in a health emergency.

It had no administrative authority over more than 3000 regional disease-control offices, many set up in the 1950s.

They took orders and funding from local governments, and often resented interference from Beijing.

No legal quarantine powers

Unlike the US CDC, the Chinese agency had no legal powers to quarantine people in an emergency, or to communicate directly with the public. It was far smaller, with about 2000 full-time staff, compared with almost 12000 at the U.S. CDC.

“From the beginning, it really wasn’t being given the financial support, the opportunities for growth and the explicit roles that it needed,” said Jeffrey Koplan, an Emory University professor, former U.S. CDC director and longtime adviser to the China CDC.

One early success was China’s first internet-based disease-reporting system, which was launched nationwide in 2004 and upgraded with WHO help in 2008.

The system, which among other things required doctors to log any single case of unexplained pneumonia as soon as it was discovered, would send automated alerts to local and national disease-control officials.

By 2013, it had reduced the average reporting time from five days to four hours, according to Chinese health officials.

Still, it was dependent on doctors and local officials obeying the rules. Often, regional governments required doctors to discuss cases with hospital bosses and local health officials before logging them.

“A world-class reporting system is fantastic only if it’s put in use properly,” said Adam Chen, a health-policy professor at the University of Georgia, who works closely with the China CDC.

Soon after the Chinese agency was established, the U.S. CDC began posting officials to the American embassy in Beijing to help train hundreds of China CDC staff. For the U.S., the goal was to enhance preparedness for emerging pathogens, many of which it expected to come from China.

After Mr. Xi took power in 2012, Beijing had an additional motive: boosting its international influence. President Xi’s signature foreign-policy initiative, the Belt and Road global infrastructure program, included plans for a “Health Silk Road” whereby China would help developing countries control disease.

Staffing problems

The China CDC took its first big step in that direction in 2014 by sending a team led by Dr. Gao, then its deputy director, to Sierra Leone to help combat an Ebola outbreak. Another team went to Liberia. The U.S. and China agreed to collaborate on setting up an Africa CDC.

Despite its higher profile abroad, the China CDC was facing staffing problems at home. It struggled to find good new recruits after moving from Beijing’s city centre to a remote suburb, people who worked there said. Salaries were low.

“A physician midcareer, they were lucky to be able to afford a dinky apartment and a teeny tiny car, or a motor scooter” working for the China CDC, said George Conway, the U.S. CDC’s resident adviser in China from 2012 to 2015. People like Dr. Gao could “make buckets more working for some biotech start-up or in private practice.”

Gao takes over

When Dr. Gao took over in 2017, he saw an opportunity to boost the agency’s standing, according to people who worked with him. He was, in many ways, the ideal candidate for such a task — an embodiment of China’s growing wealth, scientific prowess and global outlook.

One of six siblings born into a poor family in north China’s coal belt, he trained first as a veterinarian but shifted to microbiology and epidemiology for graduate studies in Beijing.

After winning a British government scholarship to study at Oxford in 1991, he continued his research there and at Harvard, backed by the Wellcome Trust, a British charity.

He returned to China in 2004 as part of a wave of Chinese scientists Beijing lured back by senior posts and financial incentives.

Unlike his immediate predecessor, who was known as a quiet and diligent administrator, Dr. Gao was charismatic, fluent in English, well-connected internationally and a much-published expert on how viruses jump from animals to humans.

Dr. Gao “was the star persona,” said Dr. Conway, who worked alongside him in Beijing. “He’s a very polished kind of guy. I mean, he would have gone up quickly at the U.S. CDC, too.” In 2018, Dr. Gao hosted a World Flu Day in China, attended by the WHO chief, and in 2019, he launched “China CDC Weekly,” a publication in English and Chinese designed to replicate the U.S. CDC’s influential Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which provides details of emerging public-health issues.

US relations deteriorate

As relations with the US deteriorated, however, his position grew more precarious. In Beijing, Chinese officials with close US ties were regarded with increasing suspicion. Some US officials, meanwhile, were wary of Dr. Gao’s enthusiasm for the Global Virome Project, a program to catalogue emerging virus threats, fearing Beijing planned to use it to further strategic goals.

In 2018, after the White House designated China a “strategic competitor, ” the National Science Foundation, which had provided grants for joint research, closed its office in Beijing. The US CDC started scaling back its China program.

The withdrawal of U funding added to the China CDC’s financial and personnel problems. Its annual budget of 286 million yuan ($41 million) for 2020 was barely more than in 2016. The US CDC had a budget of $6.6 billion this year.

In a conference this May, Dr. Gao complained of funding and personnel shortfalls as well as “micromanagement” by Chinese authorities, saying: “Disease control work has clearly lagged behind our economic and social development.”

Early Warnings

Wei Guixian first started to feel sick on Dec. 10.

The 57-year-old seafood trader thought she had a cold, and walked to a small clinic near Wuhan’s Huanan market where she worked. Eight days later, she was drifting in and out of consciousness in the hospital, one of the earliest suspected cases in the outbreak.

“I thought giving birth was the most difficult thing,” she said in an interview. With this illness, “I felt I’d rather die.” Even a fully empowered China CDC would likely have missed the very first cases of the coronavirus, which probably began spreading around Wuhan in October or November, most likely in people who never showed symptoms, or did but never saw a doctor, researchers say.

By early December, however, the China CDC’s real-time system should have been flagging Ms. Wei and other similar cases admitted to hospitals and clinics, those researchers say.

They had similar symptoms, including fever, fatigue, coughing and aching limbs, but tested negative for influenza, regular pneumonia and other known illnesses, according to local doctors.

Many visited or worked at the downtown Huanan market, a vast indoor warren of stalls selling mainly seafood but also wild animals, live and dead, including badgers, hedgehogs, raccoon dogs, bamboo rats and civet cats.

Some had no exposure to the market, however, an early indication that the virus was spreading between humans.

Because the early patients went to several different facilities, and the details weren’t logged in the real-time system, no one was in a position to connect the dots between them.

“We could have known about these cases from mid-December, then we wouldn’t have ended up 50 days later with the virus out of control,” said one former deputy director of the China CDC.

Doctors treating early cases were alarmed when chest scans revealed severe lung damage. Some sent samples for testing at laboratories run by private companies, including Vision Medicals in the city of Guangzhou, according to people involved. Vision Medicals confirmed on its official WeChat account that it had tested a sample taken on Dec. 24 from a patient who got sick on Dec. 18, and said that was the earliest specimen to be tested. It declined to comment further.

By Dec. 27, at least one private laboratory had already sequenced most of the genome of the virus and identified a new SARS-like coronavirus, according to one doctor in Wuhan who saw results — three days before Dr. Gao read about the outbreak online.

The Chinese government’s official version makes no mention of either the real-time system’s failure or the private laboratories’ results. Public release of the genome sequence wouldn’t come for another two weeks.

The government’s account begins on Dec. 27, when it says a doctor at the Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine in Wuhan identified four patients with unexplained pneumonia and contacted the disease-control office of Wuhan’s Jianghan District, where the hospital and the market are located.

Wang Wenyong, a 38-year-old official in that district office, drove to the hospital, took samples and sent them to the Wuhan city disease control office the next day, according to China Newsweek, a magazine affiliated with China’s government-information office.

“Because it was three people from the same family, it was very clearly contagious, but we thought at first it might be influenza,” the magazine quoted Dr. Wang saying.

Over the next two days, he was informed of three more cases at Hubei Integrated and four at Wuhan Central Hospital — all seven linked to Huanan market — and he alerted city disease-control officials one level up the bureaucratic chain, China Newsweek said.

Dr. Wang couldn’t be reached for comment.

A doctor at Wuhan Central, Ai Fen, confirmed in an interview that she had alerted her hospital’s management about four cases on Dec. 28, and they had then informed the Jianghan District disease-control office.

She added a detail not mentioned by the Chinese government: She also sent a sample for laboratory testing, and the results, which arrived on Dec. 30, identified a SARS-like coronavirus, she said.

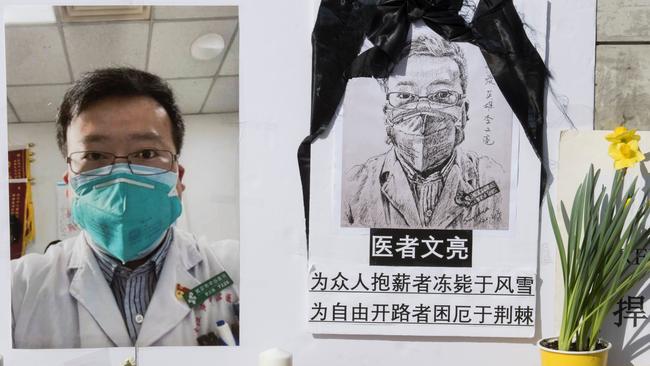

Alarmed, she shared those results with colleagues, who passed them to others, including Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist whose death from the coronavirus would later trigger an outpouring of grief and anger online.

When Dr. Li saw the result, he alerted more than 100 medical-school classmates, telling them in a group posting on WeChat that afternoon there were “7 SARS cases confirmed at Huanan Seafood Market.” He sent an update later saying “coronavirus confirmed, and type being determined” and warned the group not to leak the information.

It leaked anyway and circulated widely on social media.

For local officials, the timing could hardly have been worse. Wuhan had just spent billions of dollars hosting the Military World Games, involving athletes from 110 countries, in a bid to raise its profile. Local leaders were campaigning for Wuhan to be elevated to the same status as megacities such as Beijing and Shanghai, which would grant its Party chief a seat on the Politburo, currently comprising China’s top 25 leaders.

Politics of secrecy

President Xi attended the opening ceremony, praised Wuhan’s effort to host the event and led local authorities to believe the decision could come within weeks, according to one city official. “The whole mindset was to reduce a big problem into a small one, and a small one into nothing,” the official said. “Nobody had anticipated the scale of the outbreak.” The city was preparing for an annual policy-setting meeting involving hundreds of local officials and political advisers, and for the Lunar New Year holiday, when millions of residents travel domestically or overseas.

Local authorities moved fast to shut down the online chatter, deleting Dr. Li’s messages. He and Dr. Ai were both officially reprimanded by hospital authorities, according to people close to them.

Regional officials were trying to gauge the scale of the problem. According to an internal report dated Dec. 30 and seen by the Journal, the provincial, city and Jianghan district disease-control offices launched an investigation into the cases from Wuhan Central and Hubei Integrated hospitals.

They found that a total of 25 suspected cases had fallen sick since Dec. 1, and examined 20 of them, all of whom had contact with the Huanan market, the report said.

The west side of the market, where most of the suspected cases had stalls, was especially unsanitary, with “rubbish piled everywhere, a damp floor and poor ventilation,” the report said, recommending it be cleaned and disinfected.

The report went to the city and provincial governments, but not to Beijing. The Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, the local health department, which reports to the city government and the NHC, reacted by issuing two internal notices. One asked hospitals to search for other unexplained pneumonia cases linked to the market; the other ordered them to tighten safety procedures.

Those were the notices that were leaked and spotted online by Dr. Gao. The WHO, which monitors information about potential outbreaks online, first learned the news the same way, picking up the reports around 11am. Beijing time on Dec. 31, WHO officials say.

A team of China CDC experts — led by Li Qun, head of its Public Health Emergency Center — and other NHC personnel rushed to Wuhan that morning.

Dr. Li’s team came up with a textbook plan: Sample goods and surroundings at the Huanan market, track wildlife suppliers, test market workers, investigate clinics nearby and examine patients.

Over the next few days, those plans would repeatedly come into conflict with those of other local and national officials.

By the time Dr. Li’s team reached the market early on Jan. 1, the clean-up, as recommended by the Dec. 30 report from local agencies in Wuhan, was in full swing.

The Wuhan office had sent a team to the market in the early hours of Dec. 31 to take samples and remove some animals, and dispatched a local company, Jiangwei Disinfection, to sterilise the area.

Lu Junqing, the 31-year-old company manager, said he was given strict instructions by local officials not to talk to the public.

“The government was afraid that if pressure from public opinion was too great, it would have a negative impact,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Gao had been confident that his team, using samples from the market, could quickly identify the intermediate host of the virus. He suspected it was a bamboo rat, but his team didn’t find the virus in any animal samples from the market, only in samples taken from stalls, sewers and other surroundings.

The China CDC hit another roadblock when it tried to get local hospitals to start using the reporting system for new cases. Some began doing so from Jan. 3 but stopped within a few days, Feng Zijian, the deputy head of the China CDC, told state media in March.

What happened, according to one Wuhan official, is that local health authorities issued a conflicting internal order on Jan. 4 requiring every new case be examined first by a team of hospital experts, then by district, city and provincial disease-control officials, before it could be logged in the system.

“The directive on how to report such cases was very clear: Doctors and hospitals must take great caution to report and disclose the cases to avoid causing any kind of panic in the public,” the official said.

Chinese authorities announced no new cases at all between Jan. 5 and Jan. 18, a period that also covered the annual policy-setting meetings in Wuhan.

The China CDC team knew from its training it was essential to communicate quickly and clearly with the public so that people could take precautions and to prevent misinformation.

Order to destroy samples

The NHC took a different view.

On Jan. 3, it issued an internal notice ordering laboratories that had tested samples to destroy them or hand them to the government and forbade anyone from publishing research on the virus directly or via the media, according to a copy seen by the Journal.

Dr. Gao, who was in Beijing trying to co-ordinate between local and national officials, was so exasperated that in a call with his U.S. counterpart, he came close to tears, according to people briefed on the conversation.

The NHC’s efforts to control the flow of information weren’t entirely successful.

Around midday on Jan. 3, a team of researchers at the Shanghai Public Health Clinic Center of Fudan University received a sample from a Wuhan hospital and started to sequence the genome without knowing anything about the patient or a potential link to the outbreak, according to people familiar with the matter.

In the early hours of Jan. 5, they said, a researcher who was working late saw the results: It said “very similar to SARS-type coronavirus.” The team — led by Zhang Yongzhen, who also works at the China CDC — noticed something else: a gene for a “spike protein” on the pathogen’s surface that closely resembled the one used by the SARS-causing virus to bind to human cells. That indicated human-to-human transmission was very likely.

They sent an internal notice about their findings to the NHC that day, warning that the virus could likely spread via the respiratory tract and advising appropriate measures in public places.

No such measures were adopted for another two weeks. Nor were the results released publicly for several days.

On Jan. 9, a day after the Journal reported that China was dealing with a new coronavirus, a Chinese official publicly confirmed that for the first time. Still, it didn’t publish the genome — information that is essential for designing test kits.

Two days later, the Shanghai team’s work was published online not through official Chinese channels, but by a University of Sydney virologist, Edward Holmes, with whom Dr. Zhang had often worked. Dr. Zhang declined to comment.

Dr. Holmes said he was aware of the NHC’s Jan. 3 notice prohibiting public release at the time. “We decided to go ahead because this was an issue of such global public health importance that it just had to be done,” he said.

The following day, the NHC officially shared the genome with the world. One pivotal moment, according to many people involved, came on Jan. 13, when Thailand announced its first confirmed coronavirus case: a 61-year old Chinese woman from Wuhan who had visited a local fresh-food market, but not the Huanan one. China’s leadership was growing alarmed.

In public, even some China CDC officials continued to play down the threat of the virus spreading between people: With no one using the real-time reporting system, the official tally of cases hadn’t budged since Jan 5.

Behind the scenes, some doctors and health experts were trying to convince China’s top leaders there was human-to-human transmission. Dr. Gao joined Zhong Nanshan, the hero of SARS, in a third group of experts to visit Wuhan, starting on Jan. 18.

On arrival in Wuhan, local officials appeared furtive and anxious, a person involved in the trip said. Visiting local hospitals, Dr. Zhong led the questioning, grilling staff until they eventually admitted that 14 medical workers had been infected by a single patient, this person said, incontrovertible proof to Party leaders that the virus was on the rampage.

On Jan 23, more than seven weeks after the first recorded case fell sick, authorities ordered Wuhan locked down.

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout