How the Getty Museum is surviving an inferno

The J. Paul Getty Museum’s survival against daunting odds is emerging as a near-miraculous beacon of disaster preparedness as the Los Angeles fires continue to wreak havoc.

Under siege by Los Angeles wildfires, the J. Paul Getty Museum is emerging as a near-miraculous beacon of disaster preparedness. Behind the scenes, it’s taking a small army to defend.

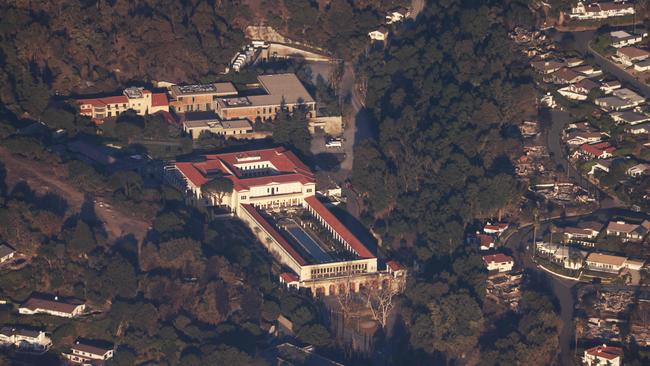

Roughly 45 museum workers have been conscripted into revolving, round-the-clock shifts to fan out and patrol the dozens of hilltop acres surrounding the Getty’s two campuses: the older Getty Villa in the Pacific Palisades, which arrays antiquities in a space designed to evoke a Roman country house, and the newer white-stone Getty Center in Brentwood where Vincent van Gogh’s “Irises” is displayed.

Fire extinguishers in hand, the museum said, the Getty’s staff scours the sparse ground beneath their boots as well as the canopies of oak trees overhead. They look for embers.

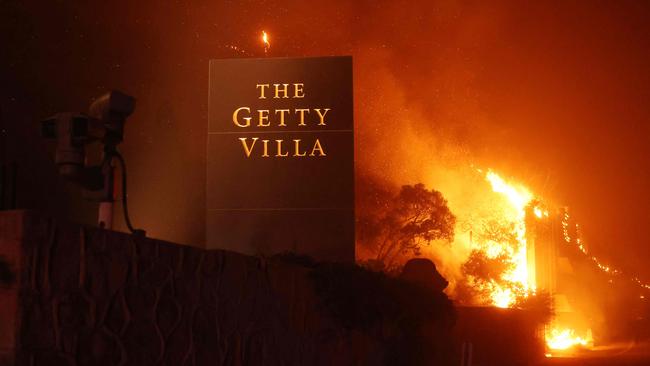

The Getty’s ongoing survival against daunting odds – the flames made it to within 1.8m of the villa’s eastern walls on January 7 – has come to represent one of the confoundingly few bright spots in a deadly cataclysm that has killed at least two dozen people and destroyed thousands of homes and businesses.

The country’s richest museum has both the experience and the resources to successfully fight back: It has a $9.1 billion endowment and has also faced down wildfires before in 2009 and 2017.

In the process, it has spent millions over the years fortifying its architecture, adding fire-prevention mechanisms to its galleries and scraping its landscape to prepare for the worst.

This week, it did, said Katherine Fleming, president and chief executive of the Getty Trust. “We’re holding up well, but it’s been totally wild,” Fleming said.

The worst of the crisis hit early, on the fire’s first night, as Fleming stood in the Getty Centre’s command station watching video footage of the Palisades fire barrel, unchecked, toward the villa.

Looking down at a wildfire-tracking app on her phone, she saw the villa encircled in red, which meant the fire was engulfing everything in its path.

Her staff members inside the villa were trapped but safe: When the villa was opened in 1974, it had fire-resistant concrete walls and tile roofs. There is also an elaborate sprinkler system on site.

“We could see the fire and we’d tell them about flare-ups, and then we’d see them leave the building to go fight it,” Fleming said. “That was frightening.”

The villa was still standing the next morning.

Acres of terrain on its eastern flank were burned and trees singed, but the manicured gardens nearest the building were still cheerily green, and all the staff inside made it out.

Its collection of 40,000 antiquities remained unbreached.

Three days later, another evacuation order came through, this time for the Getty Center located about 17km northeast, where the Brentwood fire was surging.

Building a Fireproof Structure Architect Richard Meier designed the centre to avoid burning, said Mike Rogers, director of facilities.

Its walls are clad in 111,500sq m of creamy travertine stone and surrounded with vast plazas, making it trickier for fire to spread.

Further out, the museum’s grounds are dotted with acacia shrubs and oak trees, which absorb lots of water compared with other greenery and are less likely to ignite like kindling.

The trees’ low-hanging branches are continually trimmed and brush cleared.

All these choices were intentionally made to make the museum harder to catch fire, Rogers said.

Since the museum opened in 1997, Rogers said, the groundskeepers have tapped the site’s complex network of irrigation sprinklers to soak the grass in rotating zones whenever there’s a wildfire warning.

“Everything is about being fire-resistive,” he said.

Those sprinklers connect to municipal water lines but can be fed by the centre’s own million-gallon water tank if need be; there’s another 50,000-gallon tank at the villa.

The centre’s sprinklers have clicked on at all hours since the Brentwood fire inched closer over the past weekend. The flames came to just a little over 1.5km away.

On Friday night, Fleming was outside when she got the evacuation order for Brentwood; seconds later, she heard the familiar tat-tat-tat of the sprinklers gushing on.

“The speed of that response was kind of eerie,” she said.

It also meant her team’s plan was synchronised to act quickly, and moments after that, she saw others outside stretching tape across each of the centre’s door frames to make sure no smoke filtered in, she said.

If fire ever does creep closer, the museum said the centre’s roofs, which are covered in crushed rock rather than ordinary shingles, were also designed to make fire more difficult to spread.

The museum’s air-filtration systems at both locations were updated to pressurise any air intake so that smoke or embers don’t slip in through vents.

Inside, vault-like doors have been added so that fire can be contained to one gallery without creeping into the next. Each room is equipped with overhead sprinklers as a last resort. (Curators fear water damage.)

As for the art: Its sculptures sit on pedestals that are designed to slide imperceptibly; this way, if the museum suffers earthquake tremors, the pieces don’t risk toppling.

For now, all the Getty’s art at both locations appears to be riding out the ongoing disaster in surreal silence.

The Getty Villa will stay closed until further notice; the Getty Center could reopen by Tuesday, fire willing.

Fleming just postponed a crew who had planned to start painting some gallery walls in the centre’s pavilion to prepare for a coming Gustave Caillebotte show. That exhibit is still on schedule to open February 25, she said.

None of the museums lending works for that exhibit, or an ongoing show at the villa about ancient Thrace, reneged because of the fires or asked for the museum to ship their art back, she said.

Museums know their pieces are likely to be safer staying put.

So is she.

Fleming has spent every night at the museum since the fires started, going home only on Sunday for a few hours to rest and change clothes. She said until recently, her home in Brentwood Glen was under evacuation orders, anyway.

Besides, this way the Greek historian and former provost of New York University can more easily confer with the remnant administrative staff and the larger, rotating groups of security workers who come in each shift.

This week, she and her colleagues have started hunkering down in the same large conference room, rather than staying in their offices.

They do so for camaraderie, she said, not fear: “The art is safe and so are we.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout