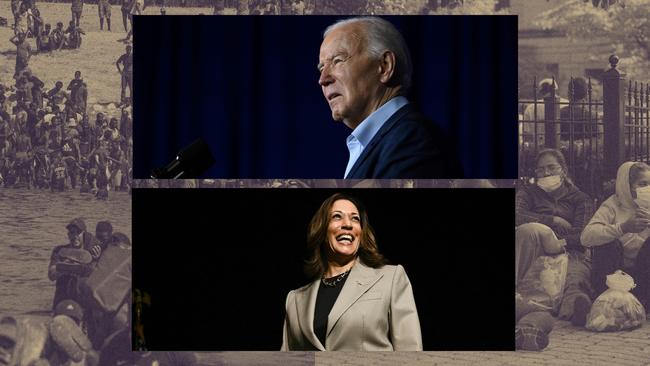

How the Democrats bungled the politics of immigration

A massive new surge of migrants turned the Biden administration’s efforts to make border policy more humane into a liability.

At a rally this week in Madison Square Garden, Donald Trump asked for what he calls his “favourite chart” to be beamed onto the giant screens. With bold type and bright colours, it shows the dramatic rise in illegal border crossings into the U.S. over the past four years. It is the chart that Trump was starting to show a crowd at the rally in Butler, Pa., in July when he turned and was grazed by a would-be assassin’s bullet. He credits the chart with saving his life.

But that’s not the only reason he likes it. “Even if it had bad numbers, I’d love that chart, but it doesn’t. It has great numbers,” he said in New York. “Look at that, it rises faster than an Elon Musk rocket ship,” he said to the cheering crowd. The chart fails to note that the increase in illegal border crossings began in the last months of Trump’s presidency, but the trend is unmistakeable — and has proved to be one of Kamala Harris’s biggest political liabilities as Election Day approaches.

In his first weeks in the Oval Office, President Biden made a sharp U-turn on Trump’s immigration policies. He ordered a halt to building the border wall, suspended deportations and ended a Trump policy forcing asylum seekers to wait in Mexico. His 28 executive orders on the issue included rescinding a Trump policy making every migrant who crossed the border illegally subject to deportation, not just those who later committed a crime. And he sent a bill to Congress to legalise 11 million people without permanent legal status. It went nowhere.

“We’re going to immediately end Trump’s assault on the dignity of immigrant communities,” he said. For most Democrats, it was welcome news after controversial Trump policies that included separating migrant families at the border.

Now, four years later, illegal immigration has helped power the political comeback of the man Biden defeated in 2020. Immigration is a top concern for voters, with only inflation a bigger worry, polls show. Immigration is also the issue where Trump holds the biggest advantage over Harris — a 16-point gap in the latest Wall Street Journal survey.

“The border may tip the election to Trump,” the pollster Nate Silver, who runs a statistical model on election outcomes, said recently in his weekly newsletter.

The story of the border over the past four years shows how the Biden team, eager to restore America’s reputation as a haven for migrants, underestimated the risks they ran in loosening controls at the border. Distracted by the pandemic, inflation and the war in Ukraine, they shifted too late to more rigorous enforcement, according to interviews with current and former officials.

By the time they enacted tougher restrictions this year, facing a difficult election battle, “It was too little, too late,” says John Feeley, a former U.S. diplomat to Latin America who is supporting Harris. Like many centrist Democrats, Feeley believes that the chaos at the border was an own goal — a political gift for Trump.

More than eight million unauthorised migrants, originating everywhere from Cuba to Colombia to China, have turned up at the southwest border with Mexico during the Biden administration, according to Customs and Border Protection data, compared with 2.1 million during the Trump administration.

Though the Biden administration has turned back millions who tried to enter, an estimated 4.6 million have been allowed in at the southern border alone, according to figures compiled by the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank. That compares to 947,000 who were allowed in at the southern border during the Trump administration.

A surge in asylum seekers

In the last months of the Trump administration, outgoing officials and career officers at the Department of Homeland Security held scores of meetings on immigration with the incoming Biden team. The DHS officials cautioned that stripping away the Trump policies too quickly could backfire, according to Trump’s deputy secretary of homeland security, Ken Cuccinelli.

“My view was that they were inviting disaster,” he recounted.

Many current and former Biden officials say that the administration has had to cope with profound changes in migration that made managing the border harder, including a global surge in asylum seekers, economic devastation across Latin America from the pandemic and increasingly sophisticated smuggling gangs that could ferry thousands of people a day to the U.S. doorstep.

“A lot of this would have happened no matter who was in office, R or D,” says Angela Kelley, the former senior immigration counsellor for Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. “We’re all coming to terms with a world where smugglers move people across vast distances and overwhelm a system that isn’t set up to provide fast, fair and final decisions on asylum or provide lawful pathways to work in places where we need the labour.”

For decades, illegal immigration was mostly made up of single Mexican males looking for work. The solution was relatively simple: intercept and deport them.

But starting in 2014, entire families began turning up to request asylum. The law requires their cases to be heard in good faith, but there is limited capacity on the border to hold them while their cases are decided and too few judges to decide the cases quickly. So they are given a future court date and allowed in. Once in, they are rarely deported, even if they lose their case. That encourages more migrants to try their luck.

Trump’s partial answer to that problem — having many migrants wait in Mexico — was criticised as unsafe and cruel by most Democrats, and the Biden administration scrapped it. But as waves of asylum seekers arrived and overwhelmed the capacity to house them, border officials began releasing thousands at a time into the U.S., a practice that critics call “catch and release.”

‘Fear and brutality is not a policy’

“There was a real push in the Biden administration to dismantle some of the harsher measures taken by the Trump administration,” said Thomas Shannon, a former senior U.S. diplomat in Latin America. “It just created this surge of people who thought they were going to be better received once they got to the frontier.”

Fernando Martinez, a Venezuelan, arrived in the U.S. in early 2022 after having heard from other migrants that the border was easy to cross.

“They came in and they came in fast,” he recounted. After a tortuous journey, he and his small son were detained in El Paso but released after four days. He recalled being taken to an airport, given a cellphone to check in with authorities and told, “Welcome to the United States.”

Jason Houser, the former chief of staff at Immigration and Customs Enforcement in the administration, says he understands why the Biden team scrapped the Trump era policies. “Fear and brutality is not a policy,” he said. But the administration, he said, lacked a coherent plan to take its place and gave no sustained attention to the issue.

Attempts to develop a solution were undermined by divisions in the administration between immigration officials with a background in human-rights activism and those worried about security, a feud that one participant called “Hatfields versus McCoys.” Changes introduced in 2022 to speed up hearings and deportation decisions by relying more on case officers were stymied by other new rules ensuring an elaborate appeals process.

One former administration official who quit in frustration said, “If you do not deter people from crossing, and show that you can turn back those that don’t have real claims, it makes sense for them to keep coming.”

The pandemic also complicated things. It ravaged Latin America, with a huge death toll and an economic contraction of 7%. Many desperate residents headed north to find better opportunities. “The single biggest determinant of whether you have immigration lower or not is what’s happening in the U.S. economy because most people are coming for work,” said Ricardo Zúñiga, a former high-ranking State Department official in the Biden administration.

The new migrants were more difficult to settle because they came from so many disparate places. Central Americans and Mexicans who had sneaked across the border in the past usually had family and friends in the U.S. who could take them in, making their presence barely noticeable.

The newer arrivals did not. They would gather at shelters or on the street. Deporting some of the newer migrants was also far more expensive, when they originated from places like China or Africa, or impossible, given that countries like Cuba and Venezuela would not take them back.

Crisis in Del Rio

There were key moments in the Biden administration when the growing chaos at the border exploded into the public consciousness. In the summer of 2021, tens of thousands of Haitians began moving north from South America, where many had settled after a 2010 earthquake shattered their homeland.

As the Haitians poured into Mexico and began heading north toward the U.S. border, some U.S. officials wanted to begin flights deporting Haitians already in custody in the U.S. to signal to those coming that they weren’t getting in. But other officials argued such deportations would be cruel and pointed to Biden’s campaign pledge to protect Haitians already here.

After weeks of argument, the administration hit on a compromise, saying it would deport some and not others. But after announcing the policy, the first set of deportation flights were scrapped after it turned out some of the passengers weren’t supposed to be there. News spread fast on Haitian social media that the deportations were off.

By September, some 30,000 migrants, a mix of Haitians, Venezuelans and others, had crossed the Texas border, with some 10,000 building makeshift shelters under a bridge in Del Rio.

Images of the squalor and Texas border patrol agents on horseback trying to stop them from entering the U.S. sparked an outcry. Biden vowed to go after the agents involved. “It’s simply not who we are,” he said.

Bruno Lozano, a Democrat who was the mayor of Del Rio at the time, recalled struggling to get Washington’s help. He said he was finally able to get the Biden administration’s attention after shutting down the bridge connecting Del Rio to Mexico.

Though a critic of Trump’s plan to build a wall, Lozano said the Biden administration’s welcoming rhetoric toward migrants essentially condoned their unlawful entry. “We’re an immigrant nation. But we have law and order,” said Lozano.

The public embraces enforcement

The spike in border crossings since 2020 has provided Trump and his allies with powerful political ammunition. Immigration has been his trademark issue from the moment he descended the escalator in the gilded lobby of Trump Tower in 2015 to announce his candidacy, using inflammatory, often racist language about migrants that continues to be part of his stump speech.

Public opinion on immigration has also shifted dramatically in recent years. During the Biden administration, the number of Americans who say they want to see a decrease in immigration rose from 28% to 55%, while those who favour more immigration fell to 16% from 34%, according to Gallup. A recent Pew survey found 88% of voters favour stepped-up border security, and 56% now favour mass deportations.

Unauthorised border crossings are sharply down since June, when Biden issued executive orders making it far harder for migrants to claim asylum and streamlining the process. Mexico has also stepped up its own efforts to interdict migrants coming from Central America, Venezuela and elsewhere.

As the Harris campaign has emphasised, Trump torpedoed a bipartisan deal to tighten the border earlier this year. The bill would have sharply increased funding for border security, tightened asylum rules and allowed the government to shut down the border if illegal crossings passed an average of 2,600 a day for at least seven days.

“We need a president who’s grounded in common sense and practical outcomes, like let’s just fix this thing,” Harris told a CNN town hall. Asked why the government took so long to address the problem, she said: “I think we did the right thing.”

Harris’s candidacy also reflects the new realities on immigration. One of her first campaign ads highlighted border security and her record prosecuting drug cartels as California’s lawyer general. She has even stopped criticising Trump’s border wall, which she had in the past called “stupid.”

“While policies narrowing access to asylum and expanding the border wall were once demonised by Democratic Party leaders, they are now a core element of party orthodoxy,” said Muzaffar Chishti, a lawyer at the Migration Policy Institute.

Border concerns far from the border

Growing frustration in several border states and the political opportunism of their leaders have also combined to nationalise the immigration issue as never before.

In spring 2022, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott launched what he called Operation Lone Star by sending busloads of migrants north to Democratic-run cities like New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C. Florida flew a group of migrants to Martha’s Vineyard. Abbott, a Republican, said that so-called sanctuary cities should bear some of the burden of the migrant influx that he blamed on Democratic policies.

The arrival of tens of thousands of migrants soon overwhelmed those cities, whose mayors said they were at a breaking point as shelters quickly filled up. They called Abbott’s move inhumane and cruel. But they also called for help, with New York Mayor Eric Adams even openly criticising the Biden administration as he called for resources.

“The president and the White House have failed New York City on this issue,” Adams told reporters in a news conference last year.

As of mid-September, New York had nearly 62,000 asylum seekers in city-funded shelters, nearly seven times the number housed two years before, data from the City Comptroller shows.

“The doors are open and they are open in a way, from my point of view, that is very, very disorganised,” said Niurka Melendez, a Venezuelan who directs Venezuelans and Immigrants Aid, a New York group.

She understands the frustration in the U.S. about the border. “I put myself in the shoes of an American, and I say, ‘Wow, what is this?’” she said. “This isn’t about whether I’m for or against migrants. It’s about having some rules.”