How Iran defied the US to become an international power

Despite decades of western pressure, Tehran poses a greater threat to US interests thanks to its ties to Russia and China.

The winner of Iran’s presidential election will inherit domestic discord and an economy battered by sanctions, but also a strength: Tehran has more sway on the international stage than in decades.

Iran, under Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s leadership, thwarted decades of US pressure and emerged from years of isolation largely by aligning itself with Russia and China, giving up on integration with the West and throwing in its lot with two major powers just as they amped up confrontation with Washington.

Iran’s economy remains battered by US sanctions, but oil sales to China and weapons deals with Russia have offered financial and diplomatic lifelines.

It also effectively exploited decades of US mistakes in the Middle East and big swings in White House policy toward the region between one administration and the next.

Today, Tehran poses a greater threat to American allies and interests in the Middle East than at any point since the Islamic Republic was founded in 1979.

Iran’s military footprint reaches wider and deeper than ever. Iranian-backed armed groups have hit Saudi oil facilities with missiles and paralysed global shipping in the Red Sea. They have dominated politics in Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen and Syria, and launched the most devastating strike on Israel in decades, when Hamas attacked in October. Iran launched its first direct military attack from its soil on Israel in April. It has also orchestrated attacks on opponents in Europe and beyond, western officials say.

The consequences – drones for Russia in Ukraine, the threat from Iran-backed militias, Tehran’s recent expansion of its nuclear program – will remain pressing issues regardless of who wins the second round of the Iranian election on July 5 or the US election in November.

“In many respects, Iran is stronger, more influential, more dangerous, more threatening than it was 45 years ago,” said Suzanne Maloney, director of the foreign-policy program at the Brookings Institution, who advised Democratic and Republican administrations on Iran policy.

Iran’s foreign-policy choices have come at a great cost at home for Iran. Its economy lags far behind the growth and living standards of its Gulf Arab rivals Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The Islamic regime has lost much of the public support that brought it to power, with numerous protests prompting brutal crackdowns.

“The regime has lost legitimacy, and I don’t think they have a good solution for that problem,” said Eric Brewer, a former National Security Council director for counter-proliferation. “Every time Khamenei has had a choice to open it up … he’s clamped down further.”

Iran’s growing strength marks a failure for the West. Since Jimmy Carter was president, finding an effective strategy to contain Iran has been the great white whale of Western foreign-policy makers.

The West’s go-to policy tool, sanctions, is no longer effective at isolating Tehran internationally. Iran has responded by deepening an axis with Russia and China, complicating diplomacy with Tehran even more, analysts say. Outside the Middle East, Iran’s drone industry has helped Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Western sanctions have cost Iran billions of dollars, “but what was the objective?” said Seyed Hossein Mousavian, a former longtime Iranian foreign-policy official, now a research scholar at Princeton University.

“Iran is more influential in the region than ever … China has captured the Iranian economy and Iran has moved closer to Russia.” For more than two decades, Western policy on Iran has vacillated. American presidents repeatedly shifted the balance between diplomacy and force, outreach and attempted isolation.

Case in point: When the US invaded Afghanistan in 2001, Washington sought from Iran and received military assistance and intelligence to help topple the Taliban. Months later, former president George Bush labelled Iran part of an “Axis of Evil,” along with Iraq and North Korea – a reversal that Iranians saw as a threatening insult.

Iran, meanwhile, has for decades followed a consistent long-term strategy, which it calls “forward defence,” deterring attacks by enemies while building out a network of loyal militias.

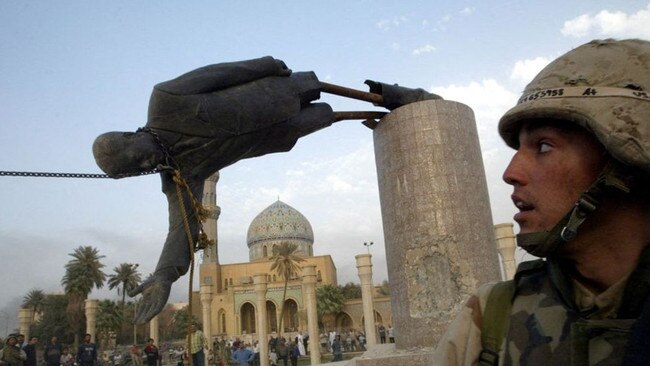

US policy has at times unintentionally contributed to Iran’s strength. The 2003 toppling of Saddam Hussein removed a sworn enemy from Iran’s borders. Washington’s failure to stabilise post-war Iraq bolstered Tehran’s influence.

After the US ousted the Taliban in 2001, American power in the Middle East was formidable. A few months after the Bush administration invaded Iraq in 2003, citing Saddam’s alleged development of weapons of mass destruction, Tehran largely halted its secret work building atomic weapons, according to US officials. It also began what proved to be 20 years of international negotiations on its nuclear program.

Yet the invasion of Iraq began a reversal of American fortunes that still benefits Iran. Its influence through politics and militias has only grown. The protracted US occupation of Iraq, during which close to 4500 US soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians were killed, turned the American public against lengthy wars in the region.

Iran is still short of its goal of pushing the US out of a region that hosts thousands of American troops and an array of alliances, with both Israel and Arab nations. Washington remains the pre-eminent powerbroker in the Middle East.

But in Russia and China, Iran now has two heavyweight allies that also have ambitions of turning back American influence across the world.

Iran has built regional strength while staying clear of red lines that could trigger direct American military action. The consistency was possible because matters of national security – including the nuclear program and military strategy – are determined not by Iran’s president but by unelected bodies, primarily the supreme leader’s office and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which has grown increasingly powerful.

Tehran’s long-term planning is also evident in its domestic efforts to defend the clerical rule against its own people.

For the past five years, a secretive unit under the Revolutionary Guard, known as the Baqiatallah Headquarters, has spearheaded the regime’s efforts to push back against secularism and what it sees as corrosive western influence, according to a new report by researchers at United Against Nuclear Iran, a US-based advocacy group.

The unit, headed by a former Revolutionary Guard commander, imposes Islamic dress codes and engineers elections, among other tasks. It aims to mobilise its own religious civil society of four million loyal young Iranians as a way to implement the ideological and cultural policies of the clerical leadership, bypassing the bureaucracy of the elected government, according to the researchers, drawing on original material from the Revolutionary Guard.

Inside Iran, policy isn’t monolithic.

Divisions have long split moderates who favour engagement with the West and hardliners who believe Iran is best placed in an alliance with Russia and China.

The debate has resurfaced during the presidential election, which will now be contested by reformist candidate Masoud Pezeshkian and hardliner Saeed Jalili after neither gained a majority in the first round of voting with low turnout. The election is being held after the death of President Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter crash last month.

Iran’s nuclear program illustrates how adept Tehran has been at exploiting wavering US policy.

The Obama administration saw a solution to the nuclear issue as necessary to reduce US involvement in the Middle East after more than a decade of war. In 2015, Iran and six world powers, including the US, Russia and China, agreed to a landmark deal to impose strict restrictions on Iran’s nuclear work for at least 10 years.

In exchange, Tehran won relief from international sanctions the US had campaigned for in previous years.

Supporters saw it as a vindication of their dual policy of pressure and engagement. They hoped it would lead to long-term containment of Iran’s nuclear program and easing of tensions in the region.

Opponents believed the agreement allowed Iran to wait 10 years and resume work on nuclear weapons with most international sanctions gone. Some criticised the deal for not addressing Iran’s regional military activities.

Meanwhile, Iran’s regional footprint grew. Iranian support helped Syrian President Bashar al-Assad survive the Arab Spring and a civil war. Iran gained deeper influence in Syria and established a land corridor leading from Tehran to Syria’s Mediterranean coast via Iraq, which it used to transport weapons and personnel. It positioned allied militias near Israel’s border in Syria and Lebanon.

In Syria, Iran also forged a partnership with Russia, which came to Assad’s aid in 2015. The relationship grew with war in Ukraine, where Iran supplies Russia with drones.

Iranian-backed militias became politically dominant in Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen, where the Houthi rebels in 2014 took control of the capital, San’a. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – important regional security partners for Washington – became enmeshed in the Yemen war.

Israel, where the government perceived the threat from Iran to be growing, didn’t follow through on threats to attack Iran’s nuclear sites. The Obama administration, Israel’s government and some Gulf Arab states were in open dispute over US Middle East policy.

“I think we were overly preoccupied with the nuclear issue and not enough on regional issues,” said Robert Einhorn, a former senior State Department official and architect of the Iran nuclear deal in the Obama administration.

Einhorn said former president Barack Obama was right to keep Iran’s regional influence separate from the nuclear talks and push back hard against Iran’s destabilising regional activities outside those negotiations.

“The problem is he didn’t follow through on that,” Einhorn said.

In 2018, former president Donald Trump withdrew from the nuclear deal and imposed a “maximum pressure” sanctions policy on Iran that punished foreign firms doing business with the country and largely killed off reviving European trade with Iran.

Despite renewed economic hardship, Iran refused to be coerced into new talks. President Joe Biden made a revival of the nuclear deal a top foreign-policy goal, but renewed talks collapsed in August 2022 when Tehran walked away from a deal.

Iran has since rebuilt its nuclear program, going much further than it had at the time of the 2015 nuclear deal and effectively reaching the threshold of developing a weapon – something it says it isn’t trying to do.

– WSJ