How a mysterious tip led to Trump conviction

When The Wall Street Journal uncovered an illicit payment to porn star Stormy Daniels, the now-former president tried to brush it aside. It didn’t work.

It was before 8am on a Saturday, days before the 2016 election, and Donald Trump’s campaign was relieved: A Wall Street Journal article, revealing that the National Enquirer had paid $150,000 to quash a former Playboy model’s story of an affair with the candidate, was attracting little attention.

“So far I only see 6 stories,” Michael Cohen, a Trump lawyer and his longtime fixer, texted to campaign spokeswoman Hope Hicks, surveying the immediate response.

“Same. Keep praying! It’s working!” replied Hicks, who was travelling with Trump on the campaign trail.

It wasn’t. Trump survived the story and, three days later, was elected president. But on Thursday — nearly eight years later — he became the first former president to be convicted of a crime, when a Manhattan jury found him guilty of 34 felonies for falsifying records to cover up another hush payment, to porn star Stormy Daniels.

Trump has faced more scandals than any politician in modern U.S. history. He bragged about groping women in a leaked videotape. He was impeached twice. His supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol. He has been indicted multiple times in criminal cases and, this year alone, has been ordered to pay more than $430 million in cases involving civil fraud and defamation of a woman who accused him of sexually assaulting her.

Yet it is his involvement in an effort to silence women who alleged sexual encounters with him, which prosecutors said amounted to an unlawful scheme to influence the 2016 election, that made the 77-year-old real estate billionaire a felon. The verdict caps — at least for now — a drama that has closed and reopened repeatedly over the course of nearly a decade.

Trump usually went on the offensive in response to the parade of bad news during his presidential term, attacking reporters and blaring “fake news” denials on social media. But he countered the hush-money reporting in the least Trumpian way: with mostly silence.

Top White House aides considered it a minor story compared with the other controversies he faced.

Privately, former aides said, he fixated on a single aspect of the story: Daniels’ looks. “Do you think I’d have anything to do with someone who looks like her?” he ranted. At one point, according to a former aide’s book, he instructed a reluctant press staffer to approach reporters on the White House lawn to “tell them she’s a horse face.” (When he took the insult public, Daniels shot back: “Game on, Tiny.”)

When cornered by reporters on Air Force One months later, Trump denied knowing about the hush money and referred additional questions to Cohen. Trump’s press staff, meanwhile, evaded questions about the payment in briefings, instead offering clipped denials that Trump had slept with Daniels, responding to a question that hadn’t been asked.

Trump has branded the New York trial a “scam,” described the judge as “the devil” and accused prosecutors of political motivations, while vowing to appeal. On Friday, in a news conference at Trump Tower, Trump again denied the sexual encounter with Daniels: “Nothing ever happened. There was no anything.”

When the Journal approached the campaign in November 2016 about the Playboy model story, Trump had already weathered more than a dozen accusations of sexual assault and the release of the “Access Hollywood” tape in which he bragged about forcing himself on women. His primary concern after it published, a former aide testified, was making sure the newspaper wouldn’t be delivered the next morning to the residence where he and his wife were staying.

And in January 2018, when the Journal broke the news that Cohen had arranged a $130,000 payment to Daniels, it didn’t set off the kind of panic that it might have in any other White House. “I don’t recall it being a significant event,” said Ty Cobb, who was White House counsel at the time. “I don’t think Trump believed for a minute at that time this was going to be a big deal legally.”

Cobb, who was primarily focused on the response to Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation, said he never considered at the time that the issue might present legal problems for Trump. “I thought it was offensive and reprehensible, and I think others certainly felt the same way,” he said. “But I wasn’t aware anybody had any legal anxiety about it.”

Over the course of 2018, Cohen would go from loyal fixer to chief antagonist for Trump, turning on his former boss after Federal Bureau of Investigation agents raided his properties in April. That August, Cohen pleaded guilty to eight criminal charges, including campaign-finance violations, and told a federal judge that Trump had directed him to make the hush payments — the first time he implicated the president in federal crimes.

By the end of Trump’s time in office, the hush-payments saga seemed to be in the rearview mirror, as Cohen reported to prison and Trump grappled with an onslaught of other dramas, from the Mueller report to impeachment to a global pandemic.

Sarah Matthews worked on Trump’s re-election campaign in 2019 and served as White House deputy press secretary in 2020. She said she didn’t recall having a single conversation about the hush payments during those years.

“For someone who has basically been Teflon to any scandal,” she said, “this is finally the thing that seems to have stuck.”

The original tip

The hush-money reports that fuelled Cohen’s prosecution in federal court and led to Trump’s state felony conviction began with a tip received by the Journal on Oct. 17, 2016. The tipster said a Los Angeles lawyer with the initials K.D. had been working on cases involving women who alleged they had romantic relationships with Trump.

Reporters soon found Keith Davidson, who had a history of representing clients with compromising information about celebrities. His law firm website listed Daniels on the “Representative Clients” page.

The Journal learned that another woman, Karen McDougal, a former Playboy Playmate, had been in talks with ABC News earlier in 2016 about sitting for an interview about an alleged affair with Trump that she said began a decade earlier, but McDougal and her lawyer had walked away. Her lawyer’s name: Keith Davidson.

The explanation for McDougal’s reticence with ABC was found inside a brown folder with a ribbon tie that someone handed off to a Journal reporter in a furtive meeting beneath the brass clock in Grand Central Terminal on Nov. 4, 2016 — four days before the election.

The two documents inside included a retainer agreement that said Davidson’s services to McDougal would entail pursuing claims against Trump or “negotiating a confidentiality agreement and/or life rights related to interactions” with him.

The other document was a contract McDougal had signed in August 2016 with the parent company of the National Enquirer, American Media Inc., whose chief executive, David Pecker, was a known ally of the Republican presidential nominee. The contract provided McDougal $150,000 in return for the rights to her story of the affair with Trump.

It also guaranteed her appearances on two covers of American Media-owned magazines and gave the publisher the option of running fitness advice columns under her name. As American Media would later admit in a nonprosecution deal with federal authorities, these were fig leaves that obscured the primary purpose of the agreement: to bottle up McDougal’s story about Trump and prevent her from telling it elsewhere.

The Journal’s report on the hush-money payment to McDougal, based on the documents and other people familiar with the agreement, noted that tabloids had a name for source contracts designed to keep a story out of the news rather than beneath a headline: “catch and kill.”

The Nov. 4, 2016, story broke late on a Friday. Its lack of purchase in the churn of the final days of Trump’s campaign was cause for celebration in the Trump camp. The article represented a sliver of a broader effort by Trump, Pecker and Cohen to suppress negative news about Trump during the campaign, “an agreement among friends,” Pecker later testified. New York prosecutors would call it an unlawful conspiracy to promote Trump’s election.

The story mentioned that Davidson had represented Daniels, and that she also had been in discussions with media to publicly disclose a sexual encounter she said she had with Trump before abruptly cutting them off. But that was the extent of the Journal’s knowledge at the time. It would take another year or so of on-and-off reporting to confirm that Daniels had received a pay-off, too.

As Cohen and Hicks texted about the McDougal story’s lack of traction, the Trump lawyer told her that he had a weapon in reserve, a statement from Daniels “denying everything.”

“I wouldn’t use it now or even discuss with [Trump] as no one is talking about this or cares!” Cohen wrote.

The Journal’s reporting on Daniels picked up speed in the middle of 2017, Trump’s tumultuous first year in office. A late-night dinner and cocktails with a person who was in a position to know what had become of Daniels provided the first solid piece of information. “Think taxis,” the person told Journal reporters.

In other words, think “Michael Cohen,” who had a side hustle as an owner of taxi medallions.

By January 2018, the story had legs. Cohen, the Journal learned, had paid Daniels $130,000, using a company called Essential Consultants that he’d formed in Delaware to wire the money to Davidson on Oct. 27, 2016.

When the Journal first approached the White House about the story, aides were grappling with the release of “Fire and Fury,” a book featuring extensive criticism of the president by his former advisers. The story of the pay-off to Daniels, reported by the Journal on Jan. 12, initially raised few eyebrows, former aides said.

“I don’t think people realised exactly how bad it would be,” said one former aide, who said there was “so much other crazy shit blowing up at the time.”

Once the story was published, Trump asked Hicks, then the White House communications director, how it was playing, she testified at Trump’s trial in May. He wanted to know “my thoughts and opinion about this story versus having the story — a different kind of story — before the campaign, had Michael not made that payment,” she recalled. “I think Mr. Trump’s opinion was, it was better to be dealing with it now, and that it would have been bad to have that story come out before the election.”

Aides were more concerned about first lady Melania Trump’s response than the president’s, former aides said. Trump was married to his wife at the time of his alleged affair with Daniels.

Stephanie Grisham, the first lady’s press secretary, in a 2021 book recounted calling her boss to tell her the story was coming. “She didn’t seem surprised,” Grisham wrote. In the weeks that followed, though, she saw glimpses of the first lady as a “pissed-off spouse.” She edited mention of her husband out of a tweet commemorating his first year in office. She tweeted a photo of herself “on the arm of a handsome military aide.”

Weeks later, as more details emerged about the hush payments, the first lady called Grisham as they prepared to fly down to Mar-a-Lago for the weekend to say she wanted to drive to Air Force One ahead of the president. “I do not want to be like Hillary Clinton, do you understand what I mean?” Grisham recalled Melania Trump telling her. “She walked to Marine One holding the hands with her husband after Monica news and it did not look good.”

The president, meanwhile, appeared more preoccupied with some of Daniels’ more personal remarks than with the political ramifications. After Daniels described the president’s penis as “smaller than average” and “like a toadstool,” Trump called Grisham and told her it was “all lies” and that “everything down there is fine.” (“What the hell was I supposed to say to that?” Grisham wrote.)

Struggling to deflect

Publicly, the White House was struggling to deflect questions from reporters about Trump’s awareness of the hush payments. In a press briefing in February, Raj Shah, the White House deputy press secretary at the time, tried to sidestep a question about whether Trump had known that his lawyer had paid off a porn star. “I haven’t asked him about it, but that matter has been asked and answered in the past,” Shah said. Pressed for more, he refused to commit to ask Trump about it, saying only, “I’ll get back to you.”

As the pressure built on the White House, Cohen, Trump and the Trump Organisation’s longtime chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, collaborated on a statement that Cohen provided to news organisations on Feb. 13, 2018, Cohen later testified in Congress.

The statement said that Cohen had used his own funds to pay Daniels; that neither the Trump campaign nor the Trump Organization were parties to the deal; and that neither had reimbursed Cohen.

That was technically true. Prosecutors said that Cohen received the first of 11 reimbursement checks disguised as legal retainers later that month. The check was dated Feb. 14 and cut from a trust that held Trump’s companies and assets. Most of the remaining checks came from Trump personally.

At Trump’s trial, prosecutors produced notes in Weisselberg’s handwriting that showed how Cohen would be repaid. Cohen testified that he discussed the reimbursement plan with Weisselberg and that Trump approved it. Trump’s lawyer argued Cohen received the money for legal services, not as repayment for the hush money.

After sending the statement to news media describing his payment to Daniels as a “private transaction,” Cohen later said in a deposition, he got a call from Trump while the lawyer was on his way to Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. The first lady was also on the line.

Trump asked him why he’d paid Daniels, according to Cohen.

“Well, because sometimes, you know, just because something’s not true doesn’t mean that it can’t hurt you,” Cohen said.

“Wow, Melania, do you believe that? He took $130,000 out of his pocket,” Trump said.

Trump then asked why Cohen hadn’t told him about the payment.

“Well, I figured I would tell you, but I expected you were going to lose the election. You know, then I would have told you. But, unfortunately, you won, and, you know, I guess I’ll just call it a cost of doing business,” Cohen told him.

Cohen said in his deposition that he knew the conversation was for Melania Trump’s benefit and that she saw through the lies.

He was right: The first lady privately said she didn’t believe her husband’s denials. Of Cohen’s claim that he had acted alone, Melania Trump said, “Oh, please, are you kidding me? I don’t believe any of that bullshit,” according to Grisham, her former aide.

Piercing the wall

The evasion strategy wouldn’t be tenable for long. On March 7, press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders was asked whether Trump approved of the Daniels payment.

“Look, the president has addressed these directly and made very well clear that none of these allegations are true,” she said.

CNN’s Jeff Zeleny pressed her repeatedly on when and how he had addressed the matter and whether he knew about the payment.

“Not that I’m aware of,” she said.

For three months, Trump managed to avoid answering any questions about the Daniels payment. That ended in April, when Catherine Lucey, then an Associated Press reporter, got to him aboard Air Force One. She asked if he knew about the $130,000 payment to Daniels (“No,” he said) and why Cohen had paid it if there was no truth to the allegations of a sexual encounter.

“Well, you’ll have to ask Michael Cohen. Michael is my lawyer,” he said.

Days later, the FBI raided Cohen’s properties, seizing records including those related to the Daniels payment. The move — and in particular the seizure of records related to Trump — incensed the president. In a meeting with military leadership at the White House that evening, he called the move a “disgrace” and an “attack on what we all stand for.”

Trump aides began to recognise that the story might stick.

“Initially, it was a story for a couple days and then the next crisis happened,” one former aide said. When Trump addressed the allegations on Air Force One — and Cohen was raided by federal prosecutors a few days later— “it threaded a lot of different stories together,” the former aide said.

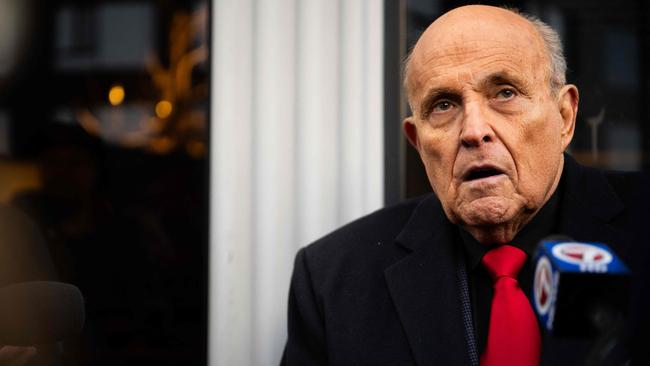

In May, the White House strategy of ignoring the question hit a major hurdle: Rudy Giuliani.

The lawyer, who had just joined Trump’s legal team for the Russia investigation and would become known for his erratic statements on the president’s behalf, went on Fox News and announced that Trump had reimbursed Cohen for the Daniels payment, though he said Trump didn’t know about the “specifics … as far as I know.”

In an interview with the Journal, Giuliani suggested that Cohen had made the payment without Trump’s knowledge at the time, saying Cohen “had discretion to solve these.” He claimed that Trump was “very pleased” that he had gone public with the information.

That summer, Trump’s attacks on his former lawyer escalated as it emerged that Cohen had taped a conversation with his boss about buying the rights to McDougal’s story — a move Trump called “totally unheard of & perhaps illegal.”

“The good news is that your favourite President did nothing wrong!” he wrote.

The plea deal

In August 2018, Cohen for the first time pointed the finger directly at the president as he pleaded guilty in federal court to eight criminal charges, including violating campaign-finance laws by orchestrating hush payments to influence the 2016 election. His plea cemented his break with Trump, and prosecutors that day revealed new details about the payments, including a sham invoice Cohen had filed with the Trump Organisation to get reimbursed for the Daniels payment.

Trump, again, was uncharacteristically silent. Travelling in West Virginia that day, he commented on another federal investigation involving one of his associates, calling his former campaign chairman, Paul Manafort — who had just been convicted of fraud — a “good man.” He didn’t say a word about Cohen, or the fact that he had been implicated in a federal crime.

It wasn’t until the next day that he tweeted: “If anyone is looking for a good lawyer, I would strongly suggest that you don’t retain the services of Michael Cohen!”

In October 2018, during an interview with the Journal, Trump was holding forth on everything from the Federal Reserve to the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia. When he got a question about Cohen, he clammed up.

“I’ve discussed that so much,” he snapped. “Nobody cares about that.” He sidestepped a question about whether he had ever discussed hush-money payments with Cohen during the campaign.

Weeks later, the Journal reported that Trump had not only discussed the payments with Cohen, but had directly intervened on multiple occasions to suppress stories about his alleged sexual encounters with women. Both the White House and his outside lawyers had declined to comment or to substantively weigh in on the Journal’s reporting.

The reporters braced themselves for the Trump playbook: decrying a story as “fake news” on Twitter, then following up with intense — and often personal — attacks on the journalists who wrote it.

But the tweet never came. Instead, Trump spent the afternoon attacking the former mayor of Tallahassee, badgering the president of France over military spending and threatening to withhold federal funds from forest management in California.

His aides, privately, were less bullish. One described the story at the time as an “absolute killer.”

That December, a federal judge sentenced Cohen to three years in prison. Prosecutors in court filings provided new details alleging that Trump — identified as “Individual-1 ” — had directed and co-ordinated both hush payments, indicating they had evidence corroborating Cohen’s implication of the president.

Trump, a day after the sentencing, said in a tweet: “I never directed Michael Cohen to break the law. He was a lawyer and he is supposed to know the law.”

The pressure on Trump continued to mount. In February 2019, Cohen testified before the House Oversight and Reform Committee, where he showed checks signed by Trump, his son and his chief financial officer that he said were intended to reimburse him for the Daniels payment. Trump accused Cohen of lying to reduce his prison time.

The former Trump lawyer reported to a minimum-security prison camp in Otisville, N.Y., in May 2019 to begin serving his sentence.

But by July of that year, it seemed like Trump might be off the hook. The Manhattan U.S. attorney’s office said it had completed its investigation into Cohen’s campaign-finance violations without indicting others in Trump’s orbit. A longstanding opinion by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel said sitting presidents couldn’t be prosecuted. Jay Sekulow, a lawyer for Trump, said that day: “We are pleased that the investigation surrounding these ridiculous campaign finance allegations is now closed. We have maintained from the outset that the President never engaged in any campaign finance violation.”

But the matter was far from closed. The following month, Cohen received some visitors in Otisville — prosecutors from the Manhattan district attorney’s office, according to “People vs. Donald Trump: An Inside Account,” a book by Mark Pomerantz, who worked in the office on a special assignment.

They wanted to talk about hush money.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout