China’s property curbs send economic tremors

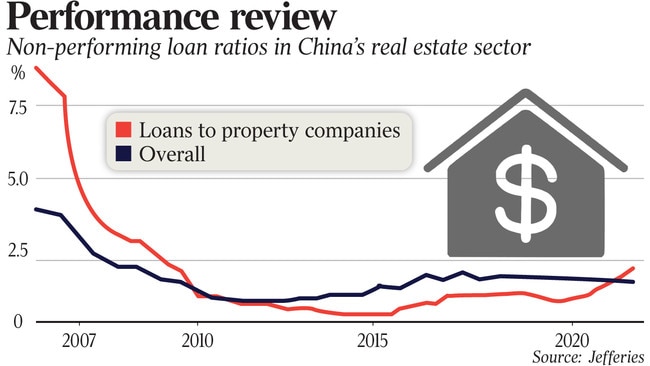

Nonperforming real-estate loans rise at Chinese banks.

Beijing’s pressure on the real estate sector is being felt far beyond China Evergrande Group, raising questions about how much economic pain China’s leaders are willing to stomach as they rein in yet another industry.

The turmoil at Evergrande, which spans street protests as well as collapsing prices for its stock and bonds, is the most visible sign of the worsening climate for Chinese property developers. Credit markets are also pricing in significant default risks for some smaller rivals, such as Fantasia Holdings and Guangzhou R&F Properties.

But economic data for August, released on Wednesday, pointed to broader difficulties, with national home sales by value tumbling 19.7 per cent year-over-year, the largest drop since April 2020.

Growth in home prices and property investment has slowed, while construction starts fell 3.2 per cent in January-August, compared to a year earlier. Chinese property stocks fell on Wednesday, with the Lippo Select HK & Mainland Property Index dropping 3.3 per cent in Hong Kong.

Policy tightening was the immediate problem for Chinese developers, but the underlying issue was that they have borrowed too much over the last decade to expand, said Mark Williams, chief Asia economist at Capital Economics.

“Regulators are trying to deal with the amount of leverage among developers, and there is no pain-free way to do that,” said Mr Williams.

Authorities had to tread a narrow path to enforce deleveraging while keeping the financial system stable, he added. “If they push too hard, then it can become destabilising.”

The property clampdown could prove to be “China’s Volcker moment”, Nomura chief China economist Ting Lu wrote in a report – in a reference to the recession-inducing interest-rate increases that Paul Volcker oversaw as chairman of the Federal Reserve, which he introduced to crush inflation in the early 1980s.

Mr Lu said Beijing seemed willing to sacrifice some growth stability to achieve its long-term goals, including lowering inequality, raising the birthrate, and cutting its dependence on foreign technology.

“Markets should be prepared for what could be a much worse-than-expected growth slowdown, more loan and bond defaults, and potential stockmarket turmoil,” Mr Lu wrote, saying that property makes up a quarter of the Chinese economy.

Worried about a housing bubble, China’s government has repeated the mantra that “homes are for living in, not for speculation”, for almost half a decade, but pressure on property developers has intensified in the last year.

Regulators have capped banks’ exposure to real estate, both in loans to developers and mortgages, introduced a system of “three red lines” that restricts more indebted developers from taking on new debts, and overhauled land auctions. Local governments have also introduced their own curbs to help rein in the market.

Already the challenges appear to be feeding into financial results across the sector. The median gross profit margin of Chinese developers tracked by Goldman Sachs fell steeply in the first half of this year, by 4.6 percentage points to about 22 per cent.

As of mid-August, developers had defaulted on $US6.2bn of high-yield debt this year, a higher total than the previous dozen years combined, according to Morgan Stanley.

Moody’s Investors Service, which recently lowered its outlook on the sector to negative, forecasts industry-wide contracted sales could fall as much as 5 per cent in the next six to 12 months, as sales volumes fall, price rises slow, and given that activity was robust in the last six months of 2020.

Signs of stress are also appearing in banks’ loan books, as more of their corporate loans to developers go sour, although so far their mortgage portfolios are holding up well.

“We haven’t seen such a high level of bad property loans in more than a decade,” said Shujin Chen, a banking analyst with securities firm Jefferies.

At Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, for instance, nearly 4.3 per cent of property loans were non-performing at the end of June, up from about 2.3 per cent six months earlier.

Property makes up about 7 per cent of all corporate loans at ICBC, China’s biggest commercial bank by market value.

Ms. Chen said the build-up in banks’ bad loans was concerning and would be more alarming if home prices start falling, since banks would suffer bigger losses as the value of property held as collateral for loans falls.

“The overall credit risk for banks is increasing,” said Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist in the Asia Pacific region at Natixis, a French financial firm. She said she was worried about mortgage repayments if home prices drop and the economy keeps slowing.

The effects could also show up farther afield, in businesses that rely on new homes as a source of demand, such as building companies and makers of construction equipment, furniture and household appliances.

Shares in Skshu Paint Co., an Evergrande supplier, are down 31 per cent in the last three months. The company said earlier this month that Evergrande had settled unpaid bills worth about $US34m by giving it three unfinished property projects, which were based in Hubei province and in the southern city of Shenzhen.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout