How an American cardinal beat the odds to become Pope

As the doors to the Sistine Chapel swung shut, and the conclave began, opponents of Italian Cardinal Parolin already had a strategy.

Cardinal Robert Prevost, seated beneath Michelangelo’s monumental fresco of the Last Judgement, buried his head in his hands as the sound of his name echoed off the walls of the Sistine Chapel.

It was Thursday morning, and the prelates running the conclave were reading out the ballots. The papal election was shifting the way of the Chicago-born cardinal. His tally was rising with each round of voting, while support for the early frontrunner — Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin — was stagnating.

A realisation weighed visibly on Prevost, said three cardinals who watched his reaction: He was on track to become the 267th pope of the global Catholic Church, with its 1.4 billion faithful.

By late afternoon it was all over. Votes for Prevost reached the winning threshold of 89, or two-thirds of the 133 voting cardinals present in the chapel. Applause rang out from banks of red-clad cardinals. Prevost, sitting with his eyes closed, stood up and mustered a smile as the historic moment sank in.

“I couldn’t imagine what happens with a human being when you’re facing something like that,” said Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin, archbishop of Newark.

The election of the first-ever American pope stunned the crowds gathered in St Peter’s Square, defied betting markets and shattered an assumption that the church would never hand its highest office to a citizen of the world’s leading superpower.

But by Thursday, the 69-year-old Prevost had become the natural choice for the cardinals secluded in the Sistine Chapel. For weeks, they had searched for a successor who offered continuity with the late Pope Francis’ dream of an inclusive and humble church — but who showed more deference for Catholic tradition and stronger managerial skills to run a financially strained city-state of global reach.

Even before the conclave began on Wednesday, a geographically and ideologically diverse bloc had come to understand that they had among them an all-rounder who checked those boxes.

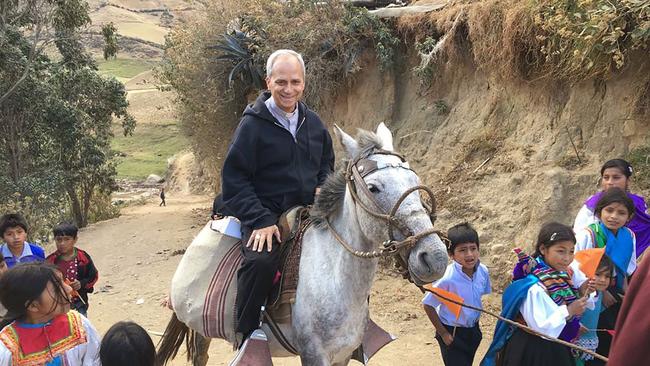

The longtime bishop of Chiclayo in Peru was from the US, but of the global south. Many of his supporters described the polyglot prelate with the same four words: “citizen of the world.” Years of missionary experience had lent him a reputation as an advocate of the poor and marginalised. He had served in the heart of the Vatican, but not long enough for its frequent scandals to taint him.

Cardinal Parolin, in contrast, had spent his career in the Vatican’s diplomatic service before rising to serve nearly 12 years as secretary of state, effectively Pope Francis’ No. 2.

Parolin was the favourite to succeed his former boss and satisfy Italian yearnings to recover an office the peninsula held for most of the church’s 2000-year history. But as an Italian saying goes, “He who enters the conclave as a pope leaves as a cardinal.”

Francis was hospitalised with a complex lung infection, eventually dying from his ailments on Easter Monday. As cardinals converged on Rome from around the world for his funeral and pre-conclave deliberations, Parolin still held a strong advantage.

“He was the best-known among us,” said Cardinal Cristóbal López Romero of Spain. “But that is not enough.”

The empty throne

The cardinals filtering into Rome in the days after Francis’ death represented the late pope’s legacy: the most geographically diverse conclave in church history. They came from 70 countries and territories, ranged in age from 40-something to 90-something and spoke a Babel of languages. Many of them barely knew each other.

Several had little in common with the Italian-dominated Roman Curia, the Vatican administration. English was the lingua franca for a new crop of cardinals. European prelates spoke about the dangers of artificial intelligence with African cardinals, who replied with laments that their continent’s natural resources were being plundered to produce tech gadgetry. Latin American cardinals discussed the migration of their compatriots to the US A cardinal flying in from Mongolia wowed his colleagues with stories of offering Mass to nomads in tents.

But Italy still boasted more cardinals than any other single country, and after three successive foreign popes — a Pole, a German and an Argentine — many felt the time had come to make the pope Italian again. Before St. John Paul II, who was elected in 1978, Italian popes had reigned continuously for 455 years.

Parolin, born near Venice, was their country’s hope. The veteran diplomat was best known in recent years for negotiating a controversial agreement between the Vatican and China that gave Beijing a say in choosing bishops within the Asian country. Despite his pedigree as a statesman, he lacked the pastoral experience of on-the-ground ministry that many cardinals were looking for.

A Latin American bloc of cardinals already viewed Prevost as their region’s best shot at retaining the papacy. Many other cardinals wanted, above all, to maintain Francis’ emphasis on “synodality,” or gatherings of bishops and laypeople to discuss the church’s challenges.

The day after Francis’ funeral, Parolin presided over a Mass, but his remarks — an opportunity to shape the agenda for the conclave — bypassed synodality.

“His not mentioning it was striking,” said Cardinal Michael Czerny, a Vatican official who was sitting in the pews.

Prevost’s name began to circulate, at dinners and in the secret pre-conclave deliberations. Cardinal Timothy Dolan, archbishop of New York, recalled how Italian cardinals were pressing him for information on his American colleague.

“Do you know this ‘Roberto?’” Dolan recalled one of them asking.

Day after day, cardinals sat through speeches on issues facing the church, from sex abuse to the increasingly dire state of the Vatican’s finances. During coffee breaks, cardinals concurred that they needed to elevate a proven manager.

With the conclave approaching, Tobin saw Prevost. “Bob, this could be proposed to you,” he said. “I hope you will think about it.”

Cardinals converge

On the last day before the conclave, Prevost delivered a speech to his fellow cardinals, and hit the note Francis’ supporters wanted to hear: He praised synodality.

“Synodality is working together,” Prevost said, according to Cardinal Luis Cabrera Herrera from Ecuador.

On Wednesday afternoon, the cardinal-electors filed into the Sistine Chapel and took an oath of secrecy in Latin. All electronic devices were banned. The Renaissance-era chapel had been swept for bugs. Its heavy wooden doors swung shut, cutting the cardinals off from the outside world.

Inside, Parolin’s opponents already had a strategy. In the first round of voting, they dispersed their votes across several candidates, to gauge their appeal.

The first ballot began hours late, partly because the 90-year-old preacher whose speech opened the conclave went on for over an hour.

When the papers were finally tallied, Parolin was in first place with more than 40 votes. The field behind him was fragmented.

As voting continued on Thursday morning, Parolin was still in the lead, but his tally was stuck in the high 40s. Prevost, by contrast, was closing the gap as the cardinals broke for lunch.

Over pasta, steak and tactical debates in a plethora of languages, Prevost emerged as the new favourite.

A frustrated caucus of Italian cardinals sat mostly among themselves, speaking in their own language. Nearby, cardinals from Asia, the Americas and Europe mingled and chatted in English, or used each other to translate.

“At lunch, things were getting clarified,” said US Cardinal Blase Cupich.

Only one more round of voting was needed.

By an auspicious coincidence, Prevost was seated in the same spot in the Sistine Chapel where Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio had sat at the 2013 conclave that elected him as Pope Francis, noted US Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who attended both conclaves.

Prevost’s final score in the afternoon vote surged to over 100 votes.

The next step fell to Parolin, as the highest-ranking cardinal in the room. Turning to the victor, he asked in Latin: “Do you accept your canonical election as the supreme pontiff?”

“I accept,” said Prevost.

“By which name will you be known?”

“Leo,” came the reply.

Cardinal Parolin was the first to kiss the ring, said Cardinal William Goh of Singapore. “Parolin is a gentleman,” he said.

Leo stepped into the Room of Tears, where new popes change into the white papal cassock for the first time. Nearby, ballots were being burned. White smoke soon billowed from the slender smokestack over the Sistine Chapel. The cheering crowd waved flags from all over the world as the name of the new pope was announced.

Two elderly Italian women near the back of St. Peter’s Square scanned their phones. One looked and said to the other: “Americano …” Her friend shot back a perplexed look: “Americano?”

Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout