China a formidable threat that grew while we looked away

China’s rise is more than a problem. It’s a puzzle. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, most Western analysts have assumed that China is a communist country in the way that France is a Catholic one. That is, there remain Marxist believers in China and practising Catholics in France, but Beijing is as little guided by Marxist ideology as Emmanuel Macron is led by the precepts of Pius IX.

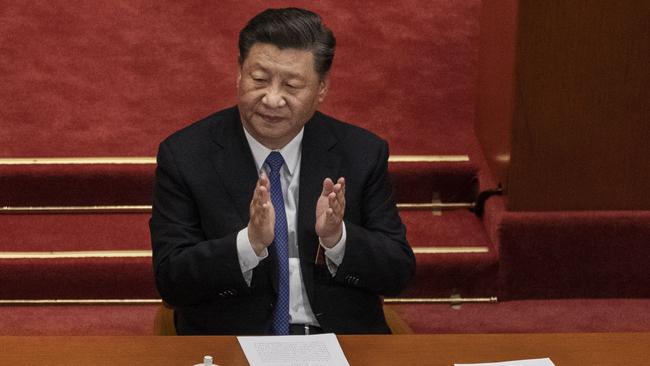

That turns out not to be true. While Xi Jinping likely spends little time reading Marx’s Grundrisse or debating the labour theory of value with his comrades, today’s China combines a Leninist party structure with state control (if not always ownership) of the means of production, a planned economy, an intolerant atheism and a ruthless determination to hold on to power at all costs. That Beijing incorporates market mechanisms into its communist system is not new; Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy in 1921 to speed recovery from the Russian civil war. But the Chinese Communist Party — armed with information technology that lets it monitor and control economic activity on a scale Lenin could only dream of — has grafted market mechanisms on to a communist state structure with great success.

Call it neocommunism or digital Leninism — it’s real. And while the US foreign policy establishment was congratulating itself on the end of history, China grew into a more formidable world force than the Soviet Union ever was.

As the Tibetans and Uighurs can tell us, the new system is as ruthless as old-style communism and, thanks to technology, far more effective at crushing dissent.

The West’s policy responses to this puzzling entity will have to take account of the geopolitical, ideological and economic dimensions of the new China. None of this will be easy. It’s unclear, for example, how entrenched the country’s latest bout of authoritarianism actually is. Clearly, under Xi, China has taken a wrong turn. But perhaps in the future, as a result of foreign pressure or domestic developments, the party might move again towards reform, and a different relationship with China could unfold.

In any case, the West’s goal even in a competitive relationship can’t be to stop China’s economic growth or dictate its political development. The country’s rise is a great moment in human history and we have no desire — and no power — to prevent more than one billion people from working towards a better life. Sun Tzu’s observation that the greatest general wins without fighting is still relevant; the best way to win a conflict with Beijing is to avoid it.

Nevertheless, the West’s relationship with a revisionist and possibly revolutionary neocommunist China can’t simply be business as usual. Countries such as China — and Russia — that claim they are actively seeking to undermine US interests and counter Western values need to be taken at their word. Diplomats and agents must respond to attempts to extend hostile influence in strategically important countries and proactively defend our interests.

For instance, the US can’t treat trade as a purely economic question. In neocommunist China, distinctions between state-owned corporations and private business can no longer be taken at face value. Chinese businesses and investors are under Beijing’s thumb.

Given the party’s ambitions, other countries have no choice but to monitor Chinese investment and financial flows, to audit their supply chains for key materials to eliminate any strategic dependence on China, and to eschew the use of Chinese tech that threatens their telecom and infrastructure security. China’s attempts to achieve technological supremacy through theft and illegal behaviour pose direct security threats to other countries. These dangers must be addressed, even at significant political and economic cost.

Beijing’s steady military build-up — combined with its expansionist territorial claims and increased efforts to form partnerships with countries such as Russia and Iran — has major implications for Western defence budgets. The US must scale up its efforts to ensure primacy on land, at sea, in the air, in cyberspace and in outer space sufficiently to deter any rivals.

And while repression is nothing new in China, the extraordinary measures the Communist Party uses against ethnic and religious minorities require an international response. There are many elements of Beijing’s governance that we don’t like, but we don’t insist that Chinese practice conforms to our ways to have normal relations. The deliberate destruction of ethnic cultures and religious communities, however, crosses a line that we cannot ignore.

Developing the right policies for this new situation is a difficult but necessary task. Neocommunist China cannot be allowed to dictate the terms of its engagement with a global system that it seeks to destroy.

The Wall Street Journal