Say what you will about the ailing state of our democracy, but you can’t deny that the choices expressed at the ballot box by Americans voting in record numbers in recent years have been efficiently translated into large and consequential governing programs.

With executive power and majorities in both houses of Congress for the first two years of their terms in office, both Donald Trump and Joe Biden were able to implement — on taxes and spending, trade, regulation, energy, social policy, foreign affairs and security, as well as Supreme Court and other judicial picks — legislative and executive measures that made lasting differences to the country.

Increasingly rigid party discipline, growing partisan ideological cohesion and institutional changes like reducing the scope of the Senate filibuster have moved the U.S. closer to a parliamentary system, in which electoral victory results in the execution of a broad political agenda.

But elections are supposed to have consequences for losers too. Voters not only select the way ahead for the country. They tell one of the parties: “We don’t want you. Change.”

Losing political parties that want to win again heed the electorate’s verdict and change accordingly — their leadership (usually), and, without abandoning their core values and philosophy, the policies and programs they offer.

At some point in the coming days or weeks, one side or the other will have to acknowledge (or maybe not — we’ll come to that later) that the choice it presented this time was rejected by the voters — and that it needs a new one.

The self-mortification will be especially painful because on both sides there is a strong sense that this was a very winnable election. Losing when you think the other team isn’t even fit to take the field offers a sobering message: You’re even worse.

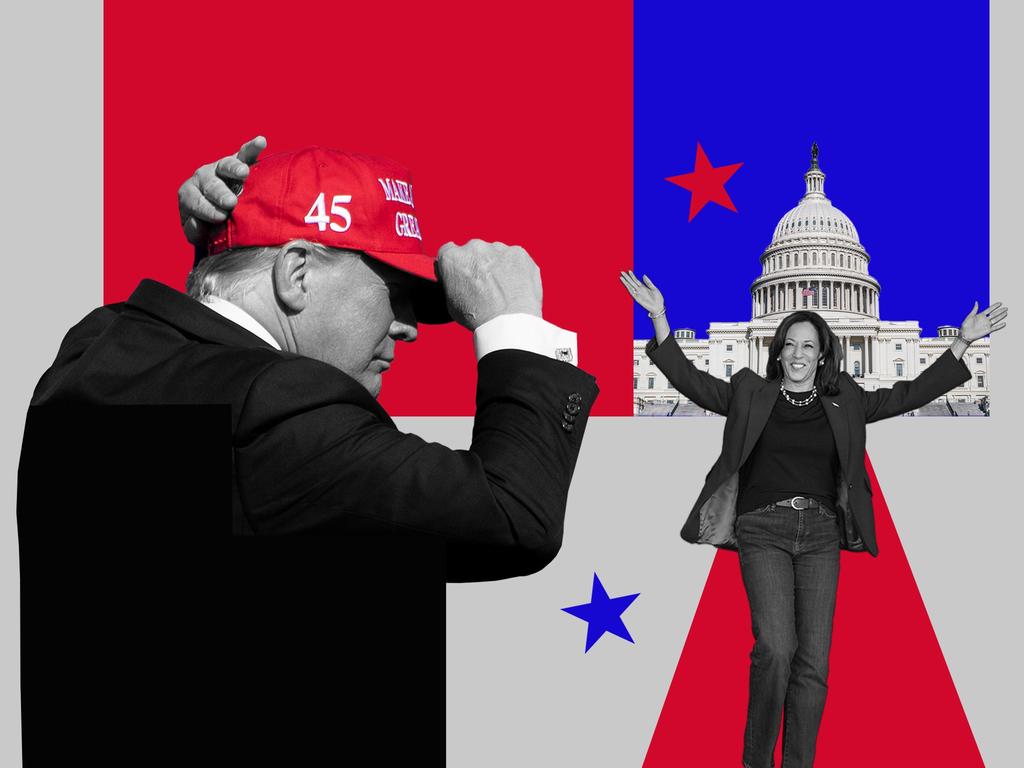

Joe Biden is a historically unpopular president, Kamala Harris a historically untested candidate. Only one vice president seeking to succeed a president in office has succeeded in almost 200 years. If a Republican can’t win in these circumstances, it will be quite a failure.

But Donald Trump is an unusual candidate with historic levels of public disapproval, whom Democrats (and quite a few independents) think morally unfit to be president. No candidate since 1892 has won back the presidency having previously lost it. If Republicans can’t win in these circumstances, what does it say about them?

Should Ms. Harris lose — and if, as seems likely in that circumstance, Republicans sweep the House and Senate — a proper reckoning for the Democrats will have to go further than acknowledging the failure to deal sooner with Mr. Biden’s evident mental incapability and Ms. Harris’s evident political weaknesses. It will need to consider the more endemic crisis in their party, to admit the reality that the radical lurch it has taken in the last decade on many social issues, the environment and immigration has moved it beyond the tolerance of large swathes of the country.

Perhaps Democrats could reflect on it this way: They have become so distant from a large section of the population — including millions of their former supporters — that the Democratic president sees fit to refer to those voters as “garbage.”

If Mr. Trump loses — even if the GOP holds onto one or both chambers of Congress — it should face a similar reckoning. There will be understandable calls for the repudiation of the man and his coterie who in three elections took the Republican Party to defeat twice and (presumably) never received a plurality of the popular vote. If a GOP defeat comes at the hands of women, the party may need to reappraise its abortion stance.

Calls to expurgate the Trump toxin won’t be enough. If the party interprets defeat this week as a signal that the electorate wants the old GOP back, it will be making an even bigger mistake. Mr Trump’s reinvention of the party was no fleeting act of individual vanity. He mobilised a new coalition of Republican voters around an emerging consensus on economics, foreign policy and cultural matters that is the basis for a new conservative dispensation. To return to the Republican Party of Bush-McCain-Romney would miss the most significant realignment in American politics in half a century.

But here’s the rub. While in a healthy democracy the losers should engage in this rethinking, they probably won’t. The result will likely be close enough again that both sides will find ways to deny it. If Mr. Trump loses, he will surely claim again that the election was rigged and prepare for another run — for him or a close surrogate — in 2028.

If the Democrats lose they will not only again denounce Mr. Trump as illegitimate. They’re likely to double down on the “resistance” mythology. The kind of radicalisation of the left we saw in Mr. Trump’s first term will return with even greater devotion to the cause of tearing down the Constitution.

Either way the destabilising, polarising stasis in our politics of a near-perfect partisan equilibrium will continue, even as the winning party gallops ahead, convinced it has a mandate to remake the country on a 51% vote share.

So like all elections, this one will have consequences. They just may not be the ones the country needs.

The Wall Street Journal

You can now listen to The Australian's articles. Give us your feedback.