The surge in international conflicts, of course, can’t all be sheeted home to the Biden administration, but the world has become an undeniably more dangerous place since he came to office.

America’s prestige has sunk, both inside and outside the country. The share of Americans who think the rest of the world looks on their country with optimism has halved from 79 per cent 20 years ago to 42 per cent this year, according to regular Gallup surveys.

In highly populous countries such as India, China and Bangladesh, most of Africa and the Middle East, most voters view Russia at least as favourably as the US, which is a shocking indictment given Moscow’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.

Prabowo Subianto, the incoming president of Indonesia, the largest Muslim nation, jetted off to Moscow in late July to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The central problem here for the US is its increasing hypocrisy on foreign policy issues, with the gap between the Biden administration’s rhetoric and its behaviour becoming wider and wider.

In his farewell address to the UN, Biden urged Israel to negotiate a ceasefire with its enemies in the Middle East, at the same time calling on the world to keep backing Ukraine in its war against Russia. Setting aside the fact the Biden administration is providing the Israeli and Ukrainian governments with vast and seemingly uncapped quantities of ammunition, how can it sustain this apparent double standard?

The Russia-Ukraine war has gone on much longer than the Middle East conflict, killed many more people and, arguably, presents a far greater risk of a nuclear confrontation. But apparently it is Israel that should make greater efforts to make a lasting peace with its neighbours.

As is the case with most US presidents, Biden’s UN speech sought to present his foreign policy decisions as motivated by the high principles of democracy, peace, sovereignty and the rule of law.

But even a cursory glance shows it is related far more to US self-interest. The US has no interest in a wider war in the Middle East into which it could be drawn to protect Israel. It does have an interest, however, in “weakening Russia to the point where it can’t do the things it has been doing”, as US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin has said. And what better way to do that than paying another country to do the fighting? This is brutal realpolitik; certainly not the actions of a selfless global power, concerned with the maintenance of liberal internationalism.

“Full-scale war (in the Middle East) is not in anyone’s interest. Even as the situation has escalated, a diplomatic solution is still possible,” Biden said in his UN speech.

Earlier this month, former US State Department mandarin Victoria Nuland intimated what Ukrainian negotiators have already revealed: that the US and Britain pressured Ukraine to tear up a tentative April 2022 peace treaty with Russia on terms that, in hindsight, look favourable.

Of course this is how powerful nations behave. But genuine attempts for global peace surely would benefit if the US dialled down the hypocrisy, which can only infuriate its closest allies.

In 1972, when Biden entered the US Senate, the world had to put up with constant claims of America’s moral superiority. After all, the US was by far the richest and freest nation, comprising about a third of the global GDP in purchasing power terms.

Now that share has fallen to 15 per cent, while the stark ideological divisions of the Cold War have withered away. Indeed, the US is starting to look more like Europe, even China, with its burgeoning national security apparatus frequently found to be spying on citizens and foreigners alike.

Many US states, including the largest ones, sought to copy China’s totalitarian response to Covid-19. The free speech protections that so distinguished the US look set to be watered down in the event Kamala Harris wins the presidential election in November. Her vice-presidential running mate, Tim Walz, already has signalled a government crackdown on so-called misinformation.

This month, unnamed intelligence officials revealed that Washington was concerned about the possibility Russia could sever undersea cables, which must have triggered guffaws in Moscow. This, after the US had (at the very least) advance knowledge, according to The Wall Street Journal, of the biggest act of industrial sabotage ever – the blowing up the Nord Stream natural gas pipelines.

In what must have prompted further hilarity around the same time, Washington scolded Russia for interfering in US elections after the US Justice Department alleged a few so-called right-wing commentators had accepted a little under $US6m from state broadcaster Russia Today via another US media company.

Moscow’s purchase of a couple of hundred thousand dollars’ worth of Facebook ads ahead of the 2016 election was probably money better spent in a bid to influence a presidential election where the two major parties spend tens of billions of dollars.

Moscow’s and Beijing’s piddling, primitive efforts to influence the US election pale in comparison to American efforts across decades to influence other countries’ elections, extending to toppling democratically elected governments not to Washington’s taste.

The US has even admitted to spending $US5bn between 1991 and 2013 in Ukraine, an astonishing sum in local currency terms, for “building democracy”. In a famous 2018 interview on Fox News with Laura Ingraham, former CIA director James Woolsey flat out admitted the US meddled in other countries’ elections and continued to do so “only for a good cause”.

None of this is lost on the rest of the world. A Pew survey from June last year found 82 per cent of people in 23 nations thought the US interfered in the affairs of other countries.

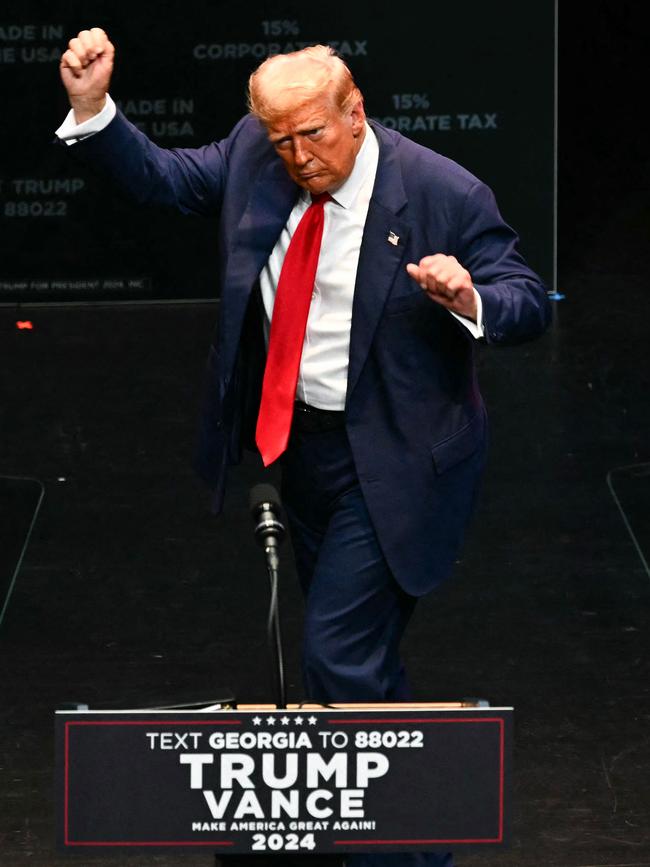

In short, the US should stop insisting it’s the pope of all nations, and acknowledge that it is motivate by self interest. The moralising, supercilious US foreign policy establishment hated Trump as president because he sought to establish good personal relations with the leaders of Russia, North Korea and others. “There are a lot of killers. You think our country’s so innocent?” he said to a stunned Bill O’Reilly in 2017, refusing to insult Putin as president.

For all its faults, the US remains a benevolent empire. But, ironically, it could burnish its influence by dialling down the hypocrisy as it navigates an increasingly complex and dangerous 21st-century landscape.

President Joe Biden’s swan song at the UN on Tuesday (Wednesday AEST) amounted to little more than a futile attempt to dress up his foreign policy failures across the past few years.