Tritium’s David Finn says he standing with giants

Brisbane startup Tritium is staking out its place in the global market for powering electric vehicles.

It’s almost a startup cliché – launching a new idea from a suburban garage. Think Hewlett-Packard, Apple and Google, each of which began in Californian garages decades ago. And so it was for Tritium, the Brisbane-based designer and manufacturer of electric vehicle chargers now positioning itself as a global player in the renewable energy sector.

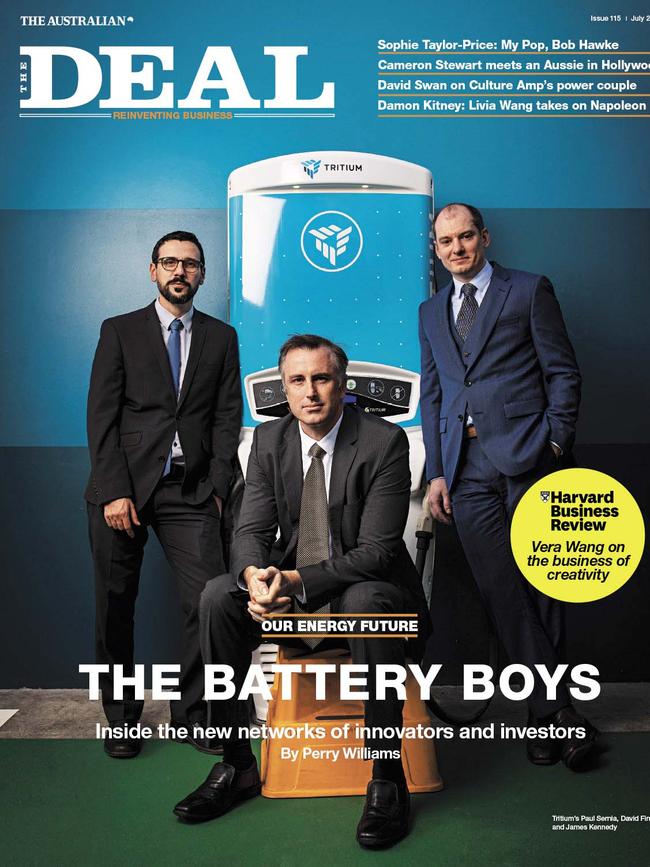

It was 2001 when David Finn and two friends used his parents’ garage at St Lucia to set up a company based on the solar product — a motor inverter — they had developed for a solar car challenge a couple of years earlier. His cofounders were chief technology officer James Kennedy and chief product officer Paul Sernia.

Finn, now CEO of Tritium, tells The Deal: “I had just done my undergraduate degree and I just wanted to run my own business and a bunch of solar racing teams wanted to buy the engine we developed. So we started showing that. It was only part-time because I was doing my PhD. Then we did cool engineering and special projects around the world. It was exciting.”

The switch to EV chargers came several years later after the group worked with the Evan Thornley-led Better Place on the first prototype charger. The company, which at one stage had Alan Finkel (now Australia’s Chief Scientist) as its chief technology officer, was arguably ahead of its time but when it shut down, Finn and friends, convinced EVs had a future, negotiated to take over the IP.

It was a big bet but Tritium raised funds and used a $1.2 million federal government grant with matching private investment to develop a charger, the Veefil-RT, billed as the world’s smallest DC fast charger. It was released in 2013 and the company has since raised $100 million — including $20 million from Trevor St Baker’s investment fund — while carving out a market for its products across Europe as well as here. Its technology is now in 30 countries. Tritium employs more than 300 people and turned over $60million last year with $100 million estimated this year. It had losses totalling $18.5 million in 2017 and 2018 but Finn says it should turn a profit in FY2021.

‘You have to be able to pivot, and that’s what we did.’

A few weeks back, there was negative press when about 25 people were retrenched, but the CEO says the changes were part of the inevitable restructuring in a growth business intent on scaling up and gaining rapid market share.

“You have to be able to pivot, and that’s what we did,” he says. “We grew very quickly in Australia and need to grow in the regions. In Europe we had one person a year ago and now we have 50.”

About a third of the jobs in Tritium’s Brisbane facility are in manufacturing, with the remaining engineers who test and develop, and sales staff.

Developing new products and services is key, with Finn seeing a convergence of four different industries — electric utilities, vehicle manufacturers, big oil and charge-point operators, like Tritium — defining the sector.

Will there be a place for the smaller players like Tritium?

“One of the most interesting things is riding the waves of the industry growth,” says Finn. “We have stood shoulder to shoulder with the bigger companies. We are competing on a daily basis with them. We have 20 per cent market share so we have similar access to supply chains. When you add innovation, in terms of IP we are at the cutting edge.”

Finn says there is still plenty of innovation to come in charger hardware but predicts there will be an inevitable commoditisation.

“We are a technology leader but you have to assume people will copy or innovate and it will converge to best practice in terms of hardware,” he says.

“In five to 10 years we will start to see that. Some say it (commoditisation) is (already) happening. I don’t agree. There is innovation (still).”

Tritium’s longer-term offering will include extensive service capability and access to high-level data analysis for clients, using data now being collected from charging stations showing how and when customers use the sites.

Finn believes we will eventually see charging hubs like today’s petrol stations, where vehicles can power up in minutes “while you get a coffee”. Car battery packs will do double duty by powering your house once you arrive home.

The EV revolution can’t be stopped, he says.

In Norway, 10 per cent of vehicles are now plug-ins; US sales of EVs grew by 80 per cent last year; and about 3 per cent of the total new car market in the UK is taken by plug-ins. Around 15 countries have mandated that by 2025 to 2040 (depending on the country) all new vehicles must be electric. The tipping point, he says, will be when EVs comprise 10 per cent of all cars on the road. “By the time you get to 10 per cent you have probably crossed the chasm,” says Finn.

He’s in business, but the EV is a passion: “There is a pay day at the end but that’s not the focus for a lot of us. It’s about cleaner and healthier cities and truly changing the world.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout