Ethnic pay gap: workers from the Middle East, Africa, Asia face discrimination

New research shows how much it costs if you’re not white at work — and the ‘skills discounting’ used by recruiters.

Multicultural Australians may be getting paid less than their Anglo counterparts, falling victim to workplace norms, policies and bias that can limit their pay and career progression.

Researchers say there is evidence to suggest a cultural pay gap, and the consensus among many Australians of multicultural backgrounds is that the gap is real and often unfairly linked to stereotypes.

Other factors which can contribute to an overall pay gap include having to apply for more roles than Anglo Australians before receiving an offer; limitations or career ceilings; and being asked to adopt certain traits to be considered for promotion.

According to MindTribes chief executive Div Pillay, the cultural pay gap sees men of ethnic backgrounds paid as much as 16 to 20 per cent less than their Anglo male counterparts, and women of ethnic backgrounds as much as 36 per cent less. First Nations women suffer the largest pay gap of all.

Pillay, who was born in South Africa and is of Indian heritage, leads the research at MindTribes, which analyses company data including salary and career progression.

She has been researching cultural pay gaps for several years.

“On average, for culturally diverse men, we see about a 16 to 20 per cent differential to Anglo men,” she says. “And for women, we see around a 33 to 36 per cent differential with women who are not born in Australia compared to Anglo men.

“We estimate that there is at least a 15 per cent difference between Anglo women and racially and ethnically diverse women.”

Pillay says research into the cultural pay gap has been at times difficult to conduct as often companies must volunteer data and many don’t even collect data on intersectional gaps.

Last week, the Workplace Gender Equality Act was amended to allow the Workplace Gender Equality Agency to publish employer data on gender pay gaps for private and commonwealth public sector employers.

Pillay says the data will shine a light on the gender pay gap but it may overlook people who are already marginalised.

“This is a classic chicken and egg story where (companies) can report on their pay gaps more easily from a gender perspective, but would be unlikely to do the rigour around investing in data collection for intersectional pay gaps,” she says.

“Women who are marginalised generally will never be seen in the data, because they are often a minority in a workforce.”

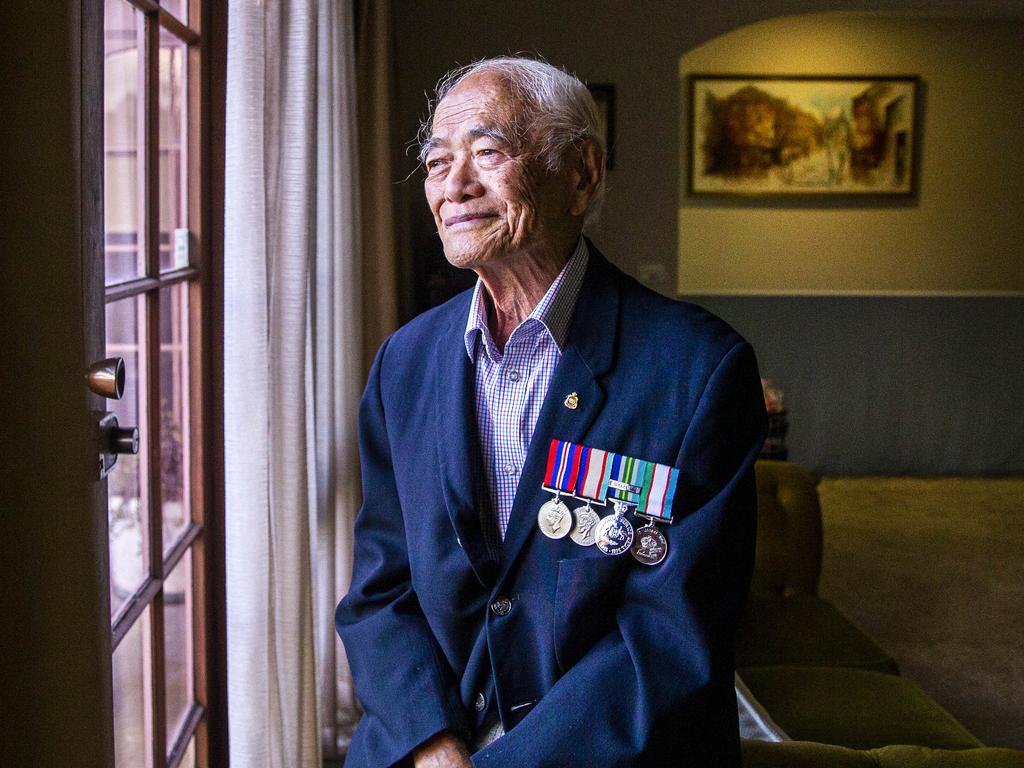

One major contributor to the gap is skills discounting, which refers to when a migrant worker’s overseas experience and qualifications are not recognised. This is often witnessed by recruiters, says Patrick Wong, the founder of IT recruitment business W Solutions.

Wong says issues related to the cultural pay gap are often hidden by jargon: businesses say they’re looking for a “good communicator”, for example.

“Whenever someone says to me that they need someone with good communication skills, I already know what they’re talking about,” he says. “It’s pretty much implying that they need to be able to speak English quite fluently.”

When it comes to salary, Wong says businesses never say they will pay someone from a culturally diverse background less. “What usually happens is when I send two candidates for the same role, one who is caucasian and one who isn’t, with the non-caucasian, the business might say they liked them but then ask if they’re open to salary negotiation.”

Many migrant workers will accept roles which pay below their skillset when entering the workforce in Australia.

“What we know from qualitative research is that migrants – especially newer migrants from Middle Eastern, African and Southeast Asian countries – will settle for roles to secure employment, despite those roles not fitting with their skills and prior international experience,” Pillay says. “Looking at that longitudinally over five years, their careers don’t markedly increase to rebalance them with previous careers that they had before coming to Australia.”

In the recruitment industry, skills discounting isn’t the exception, but the norm, Wong says. And it’s not only experienced by migrants but sometimes Anglo Australians who have spent time working abroad – often referred to as repatriates.

“People don’t regard overseas experience as on par with Australian working environment. It’s almost as if when it’s on a resume, it becomes invisible,” Wong says.

Mariam Veiszadeh, the chief executive of Media Diversity Australia, which advocates for media which is culturally and linguistically diverse, says she has witnessed the effect of the cultural pay gap.

“There is evidence to suggest that the cultural pay gap is real, and experiences throughout my own career supports this proposition,” she says.

Veiszadeh said while MDA’s work focused solely on media, research conducted by other agencies which found the gap to be true highlighted that it likely extended into the media industry.

“Given that the research from MindTribes details that women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds spend up to eight years longer in middle management roles compared to women from Anglo or European backgrounds, it’s possible to extrapolate these to the media industry and draw similar conclusions,” she says. “The research also highlights that the ethnic gender pay gap is double the national average gender pay gap, (around 33-36 per cent compared to 14 per cent). I’d love to see WGEA and other organisations conduct more research into this issue.”

Jeffery Wang, an IT sales executive, says issues limiting the career progress of ethnic Australians led to him founding the Professional Development Forum 15 years ago.

“I started the forum upon realising that we all shared the same dissatisfaction with our work and our apparent lack of progress,” he says.

The topic of a cultural pay gap has become common in the group, which meets monthly to discuss issues related to culturally diverse professionals in the Australian workplace.

Wang says it’s clear certain personality types are favoured in the workplace and are seen as being more suited to leadership positions.

“If you look at your workplace, it’s designed for extroverts. Unfortunately, in Australia, I don’t see a lot of diversity in leadership styles. The lack of Asian-Australian leaders is a visible symptom of the general lack of introverted leaders,” he says.

“Asian Australians are generally more passive as a result of their cultural upbringing,” Wang says.

“Often they are taught that it is rude to be direct and ask for what they really want, such as more money. They unfortunately feel that to be successful they need to check their culture at the door when they go to work.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout