Unheralded Anzacs ‘here to serve the country’

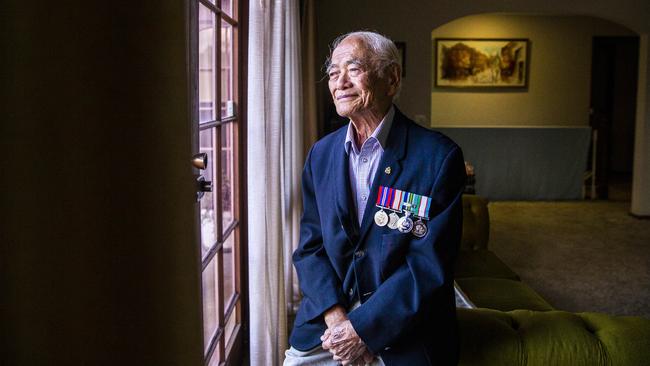

Hamilton Chan remembers very clearly the day he was called into his leading air craftsman’s office while deployed in Japan.

Hamilton Chan remembers very clearly the day he was called into his leading air craftsman’s office while deployed in Japan.

Midway through a 2½-year posting at Bofu, not far from Hiroshima, he had been servicing America’s P-51 Mustang bombers as part of the British Commonwealth Occupational Force.

“The commanding officer called me in and said, ‘look, we’ve got a letter here from immigration — they want you back in Australia to deport you to Hong Kong. Do you want to go?’,” the 94-year-old recalls.

“I said, ‘no, sir, I am here to serve the country’.”

Mr Chan was one of the more than 1000 Chinese Australians who served in World War II, a figure that had grown four times since World War I, with some soldiers serving in both conflicts.

More answered the call for able-bodied men and women to assist in the war but were faced with obstructive enlistment requirements designed to stop them — they had to be of substantially European origin or descent, to be at least 168cm tall and have a chest of 86cm.

“In those times, Chinese were not allowed to join the forces. You needed to have Anglo blood in you,” Mr Chan says.

Despite this, some soldiers went to great lengths to enlist, changing their names and often travelling up and down the east coast to try their luck at different recruiting centres.

Mr Chan says the strict requirements, in place since World War I, eventually eased.

“In the end they did. They relaxed the laws because they lost too many men. And that’s how we got in,” he says.

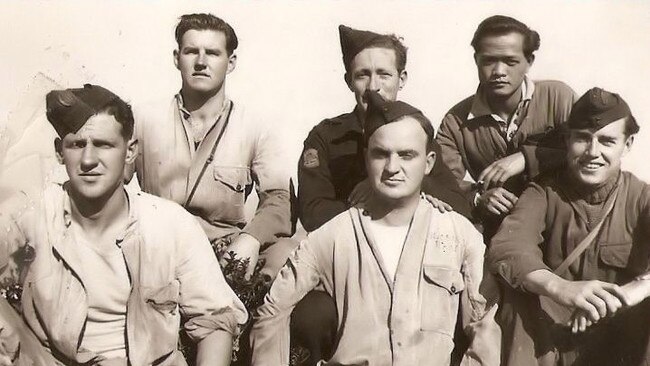

“When we’re in the forces they were mates. You were one of the servicemen so you’re all mates. Only when you’re out of there they look upon as you foreigners.”

Almost 76 years after the war ended, the contribution of Chinese Australian soldiers, which is historically not as well documented as their Anglo counterparts, is now being recognised. Their names and stories are told in a new book, launching on Sunday, a week before Anzac Day.

For Honour and Country has shone a light on 300 Victorians of Chinese descent who put their lives on the line for their country.

It is written by retired psychiatrist Edmond Chiu and Adil Soh-Lim and published by the Museum of Chinese Australian History with a grant from the Victorian government.

The book tells in some detail the stories of 80 soldiers including Alexander (Alec) Chew and Yan Cheuk Ming (James Kim).

On April 17, 1942, Chew escaped Tan Toey prisoner of war camp in Ambon, now Indonesia, and island-hopped for 48 days to get back to Australia only to enlist in the Special Z Unit and serve in secret operations in Borneo. Ming, from Casterton, Victoria, went from being a civilian overnight to assisting the British Army Aid Group as Japan took over Hong Kong. He was later captured, tortured and killed.

Mr Chiu spent three years working on For Honour and Country. What shocked him most was the discovery that Chinese Australians were considered potential Japanese spies by the then Australian Security Service in World War II. Some underwent strict security clearances by police before enlisting, he says.

“It’s quite unnerving to find that the security service considered them Japanese agents,” he says.

“Their loyalty was always to their country of birth and they were prepared to fight for it.”

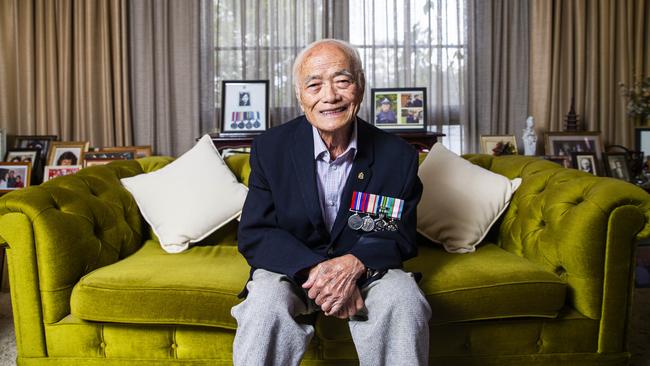

The book also includes the stories of four living Chinese Australian veterans, three of whom will attend the book launch. One of them is Mr Chan.

Born Ham Soon Chan in 1926 in Hong Kong, Mr Chan arrived in Melbourne with his father at the age of 13. He attended Richmond North Primary School and later Brunswick Technical School when he joined the RAAF.

Like many young men, Mr Chan was keen to enlist to serve his country — so much so he anglicised his name to Hamilton and 74 years later still goes by it.

In those days your neighbour would keep watch and any young man of age not serving would get a white feather in the mailbox, he recalls.

“It meant you were a coward.”

While the enlistment age was lowered from 20 to 18, anyone under the age of 21 needed parental consent. Mr Chan and his friend, John Louey, also from Hong Kong, didn’t have it.

“So we forged our father’s signatures. It was common back then,” he says.

The plan soon came unstuck when Mr Chan’s father found an army letter. They were discharged three months into their service.

After some time working late shifts in an engineering shed for the Manpower Directorate, he and Mr Louey joined the RAAF.

Following training as a fitter and turner and engineer, Mr Chan was posted to Sale to maintain planes. When the war ended he signed a two-year contract to stay on with the RAAF for an overseas posting.

At the end of 1945 he sailed to Japan.

“Our job was to make sure the Japanese don’t hide their weapons and to keep their warships at bay,” Mr Chan says of his role in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force’s base.

“Our pilots flew over Japan to maintain the occupation — make sure they weren’t up to anything illegal.”

But the nuclear fallout from Hiroshima, less than 100 km from the base, would take its toll.

The radiation got the better of some of his friends in Japan. Later he too would have cancer.

In 1948, after four years in the RAAF, Mr Chan left the services.

But Australia’s immigration authorities hadn’t given up.

“Even when I was discharged they were still after me,” he says.

“Would you believe it that I served the country — and even when I came back they were still after me?

“I fought them off … eventually I quoted an act from parliament that all ex-servicemen were entitled to study a free course under the repatriation act at either technical school or university.

“They couldn’t say anything to that!

“I managed to get a job in the public service because they did accept ex-servicemen,” he says.

“Actually I didn’t take up the course. That was one of my strategies to stay as long as I can.

“Eventually I married an ABC,” he says, referring to the colloquial term for Australian-born Chinese people. “Then white Australia started to change.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout