The Australian who helped Trump enter ‘manosphere’ and win the White House

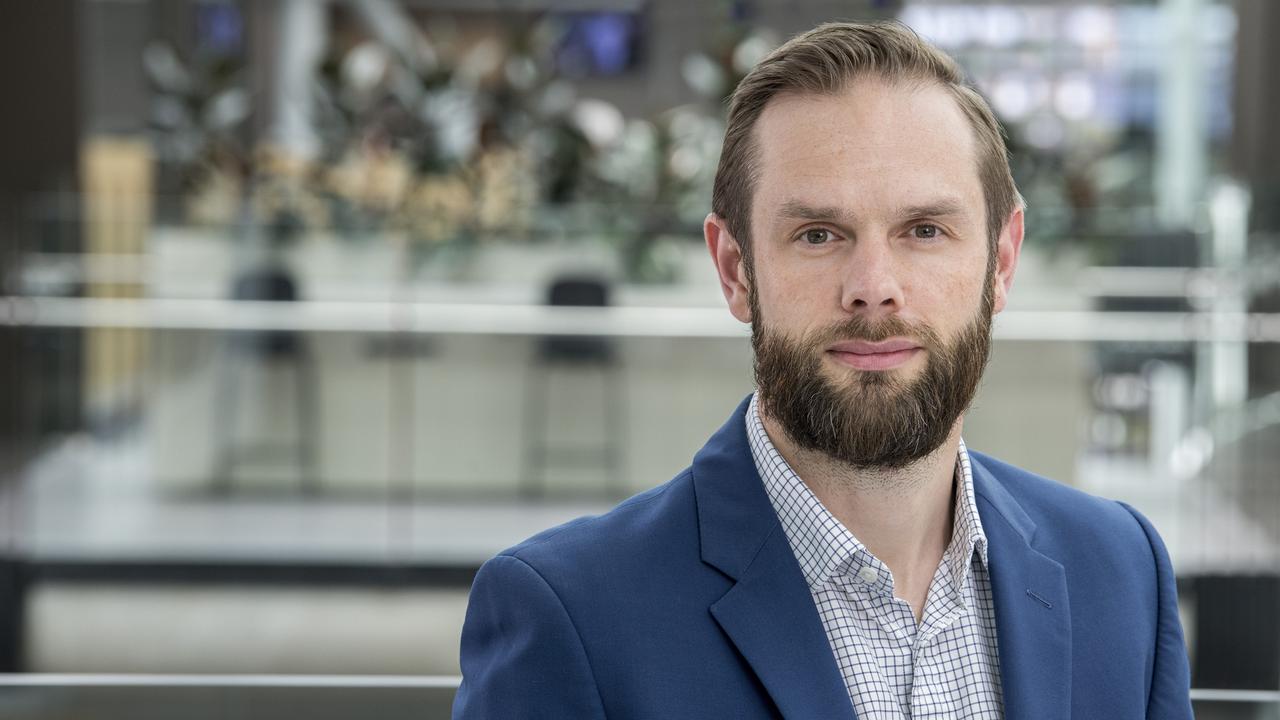

A streaming platform owned by Australia’s youngest billionaire quietly played a role in helping secure Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

An Australian streaming platform played a key role in helping secure Donald Trump’s return to the White House, connecting him with younger voters and catapulting the president-elect into the “manosphere”.

Kick, launched two years ago by Australia’s youngest billionaire, Edward Craven, hosted a live stream between Mr Trump and influencer Adin Ross in the lead-up to the election. It peaked at 580,000 live views and its replay has attracted 2.7 million more on YouTube.

It was part of Mr Trump’s online campaign, with his 18-year-old son Barron credited with encouraging his father to speak to millennials, go on Ross’s show and enter what is known as the manosphere.

“He’s very smart … He’s 18 years old. And he gives me good advice,” Mr Trump said about son at a rally in North Carolina.

The manosphere is an online community of YouTubers, podcasters, live-streamers and more who are mostly young, exclusively male and have amassed a huge following, hence Barron’s advice for his father to appear on Ross’s show.

While the tone of these online influencers vary considerably, the manosphere has attracted controversy over its advocacy of men’s rights, critiques of feminism and promotion of harmful stereotypes.

Mr Trump spent 90 minutes chatting with Ross – a foul-mouthed 24-year-old who has achieved fame playing video games for an online audience, as well as notoriety for hosting white supremacists such as Nick Fuentes and inadvertently getting Andrew Tate arrested.

For Mr Craven, who stresses that Kick is apolitical, the live stream represented a technological feat and upped the ante in the platform’s efforts to take on the big US players.

“When we first looked at the social media space and did our research, we realised that no one has really successfully entered this industry in the past decade. Thousands of companies have tried but none of them have succeeded,” Mr Craven told The Australian.

“We very quickly realised they weren’t aggressive enough. And if you want to actually make a name, if you actually want to disrupt what is not short of a monopoly in some areas of social media, you have to really push hard.

“You can’t settle for being a little bit better, you have to be a lot better. And if that comes at the sacrifice of revenue in the short term in order to go to long-term presence, that’s a commitment that we’re willing to make.”

Kick has become one of the fastest-growing tech platforms. Within 70 days of its launch, it had amassed 1 million users. This same feat took Spotify five months, Facebook 10 months and Netflix 3½ years.

While a live stream may sound simple, it requires knowhow to ensure it runs smoothly. “We work closely with our larger streamers,” Mr Craven said. “A big aspect of that is to ensure, if they are doing a large event, that we’re ready to scale our infrastructure to support the event.

Kick has attracted criticism about reportedly failing to moderate racist and anti-Semitic user comments. But the company states that its terms of service on hate speech are clear, and it will remove content that violates those terms.

“Moderating user-generated content is a challenge for all social media platforms, and we are constantly evolving our approach,” a spokeswoman said. “We take action against breaches of our terms of service and community guidelines, whether that involves a suspension, a ban, or the removal of harmful content.”

Kick forms part of Mr Craven’s Easygo empire, which employs more than 450 people in Melbourne. He used to shout the entire workforce for lunch at the city’s oldest building, Mitre Tavern, regularly. But the company’s rapid growth meant they could no longer fit in the two-storey pub.

“It was a shame when we had to pull the plug on that one, but the company now is over 450 people, with a lot of them working directly on Kick,” Mr Craven said.

“We’re looking forward to continuing to grow here in Melbourne. A lot of other companies look offshore, but all in all, Melbourne has a lot of great potential.”

And documents lodged with the corporate regulator reveal Mr Craven’s and his business partner Bijan Tehrani’s firm, Easygo Solutions – an entity that provides services to their global crypto gambling brand Stake.com and Kick – is profitable, making more than $500m in three years.

It made a pre-tax profit of $308m last year alone and paid more than $100m in corporate tax. Its $206m net profit last year would be one of the biggest by a privately owned Australian business and came after it made net profits of $74m and $76m in 2022 and 2021, documents lodged with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission show.

In January, Mr Craven signed a sponsorship deal with Sauber to secure the naming rights of its Formula One team, now known as Kick Sauber.

“Going forward, it’s really up to us to continue to grow the business,” Mr Craven said.

“We only launched kick almost two years ago. The brand was obviously completely unknown. So our market strategy was to slowly build some brand recognition globally. Kick’s main goal here is not to be a company just focused on the Australian market, just focused on the North American market, just focused on Europe. It’s to be focused on every market in the world. It’s a global social media platform.

“F1 is pretty much the most global event you could think of. So suddenly the audience starts seeing Kick scattered around throughout F1 in conjunction with Sauber, and it starts to give that brand a little bit of recognition. And with the Adin Ross and Trump stream, when that is seen, they suddenly realise, ‘hey, I know Kick, that’s a reputable platform’.”