Social media’s rabbit holes for at-risk and problematic young men

Young men are being targeted by algorithms designed to create conflict and male influencers posing as self-help gurus who then push outrageous content. So what’s to be done?

The vulnerabilities of Australian boys and young men are being exploited by harmful male influencers who at first pose as self-help gurus and later look to push their followers toward harmful stereotypes.

Experts say social media often allows toxic messaging from online personalities to thrive, with algorithms often favouring outrageous content as it gets clicks and interactions.

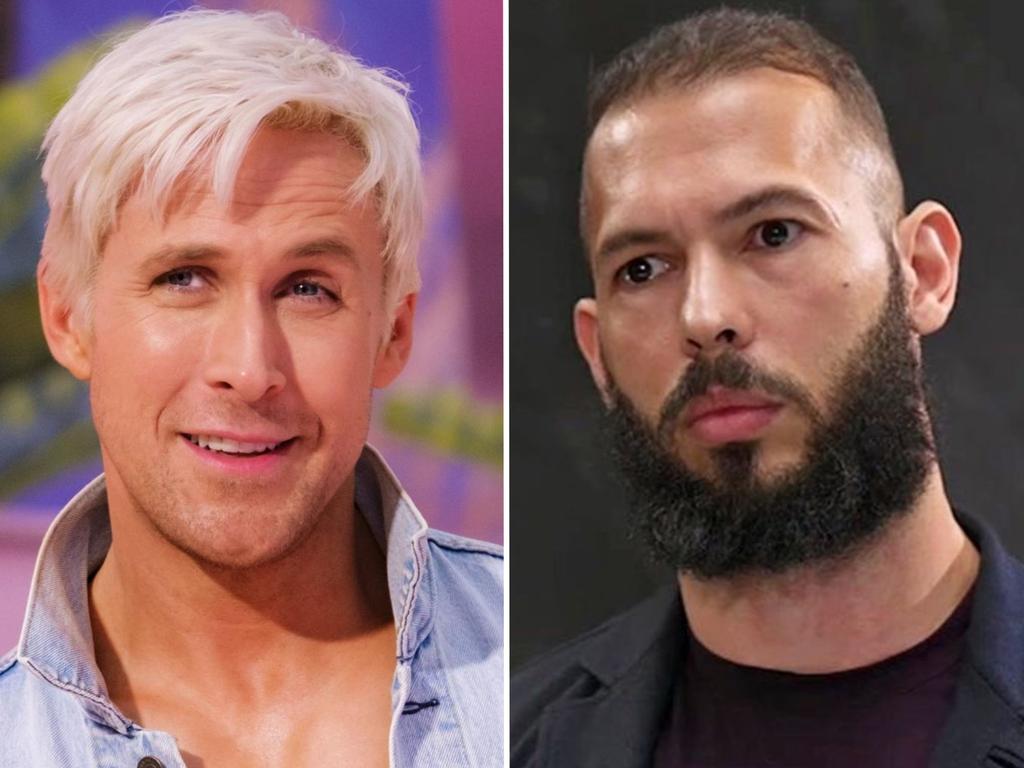

This fuelled the rise of Andrew Tate - a former kickboxer who amassed millions of young followers and 12 billion views with his advice to young men to stop feeling downtrodden, fight back against the “feminazis” and control their “bitches”.

Tom Harkin founded Tomorrow Man - an initiative aimed at combating the rise of such misogynistic influencers - said the negativity bias of people, which he described as a “psychological floor”, meant people paid more attention to shocking videos.

“And so people like Andrew Tate have the perfect vehicle for themselves,” Mr Harkin said.

Crucially, he said the increasing amount of time young people spend online was beginning to change their perception of how the world works.

“Social media and the way that it works for one has become ubiquitous. We all live on it, and young people spend an average of around eight hours a day on it. We know that that ecosystem lives on clickbait. It’s a privatised entity that is about making money by capturing attention.”

But social media companies refute that view. Jed Horner, the country policy manager at TikTok, which has about 8.5 million Australian users, told The Australian safety was a top priority and that the Chinese-owned social media company had 40,000 people globally working in its trust and safety team.

“We do not allow any hateful behaviour, hate speech, or promotion of hateful ideologies, including on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation,” he said.

“In the last quarter alone, we proactively removed over 78 per cent of content we determined violated our policies on sexual exploitation and gender-based violence and over 89 per cent on hate speech and hateful behaviour, before anyone reported it.”

Other social media giants Meta, which owns Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp, and Snap declined to comment.

To counter the rise of toxic masculinity online, Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth allocated $3.5m to launch a ‘Healthy Masculinities Project’.

“It will provide school-aged boys with a greater understanding of ways to have a healthy relationship with masculinity and will better equip this cohort to develop healthier and more satisfying relationships,” Ms Rishworth said.

The project is part of the government’s broader National Plan to End Violence Against Women and Children, which has received $11.9m.

It will target boys and men via sporting clubs and community organisations as well as online through social media.

Ms Rishworth said research found “25 per cent of teenage boys in Australia look up to social media personalities who perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes and condone violence against women”.

Ben Rich, director of Curtin Extremism Research Network at Curtin University, said some influencers channeled “latent anxieties in significant proportions of the male population” to fuel more extreme ideas.

Mr Rich released a study earlier this year which dissected the popularity of influencers who push harmful messages among younger men and school-aged boys.

“That paper was basically looking at the ways in which guys like Tate are able to sort of draw on the latent anxieties in significant proportions of the male population, kind of channel them and focus them and basically lead them to embrace more and more extreme ideas,” he said.

“There’s a theoretical model for how this occurs and how (influencers) kind of create these ecosystems in which more and more extreme ideas come out because they‘re all kind of competing with each other for attention.”

At Curtin University, Mr Rich spent most of his time researching what is called the “manosphere”.

“It’s basically a collection of online male-oriented communities that all kinds of share a critique of feminism and what they see as the displacements caused by feminism in society,” he said.

When it came to the impact of social media on young boys and men, Mr Rich said that a lot of algorithms were designed to create “conflict”.

“The algorithms that we see on things like YouTube, TikTok and X (formerly Twitter) are all about creating conflict, exposing people and making sure that people stay engaged … and the way to do that is by creating dramatic things and inflammatory titles and images.

“There’s a direct economic incentive for social media companies to facilitate these processes and unfortunately, their own kind of self moderation in it has not been particularly effective in my experience,” he said. That content later ended up “getting kind of normalised in those same online communities”, he said referring to the manosphere.

But the marketing strategies of people like Tate were not unique, and could be seen across influencers of all industries, Mr Rich said.

“You see this with just influencers in general, it‘s all about keeping people glued to your content and consuming your content,” he said.

“Whether it‘s makeup videos or cooking videos, even in those environments you see that there are essentially bidding wars between the various creators that are doing things to keep people glued to it.”

“Every time I‘m looking at a video, I’m then encouraged to go and I’m looking at something more extreme and more inflammatory, and it just becomes this self-reinforcing cycle.”

Mr Harkin - who facilitates workshops in schools for boys at Tomorrow Man - says being a young man could be puzzling and many were looking to find purpose, value and figure out what their role is.

Indeed, he said while some younger men were happy or fitted the bill for being what’s known as a sensitive new age guy - often referred to as a SNAG - others weren’t opposed to older, more traditionally masculine stereotypes.

“Having a sense of stoicism, having a sense of determination, they‘re really great traits, but those to the exclusion of being able to be vulnerable at the times you need to ask for help and acknowledge you don’t have all the answers (isn’t helpful). There’s a more nuanced territory that I don’t think is being explored enough with young men,” Mr Harkin said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout