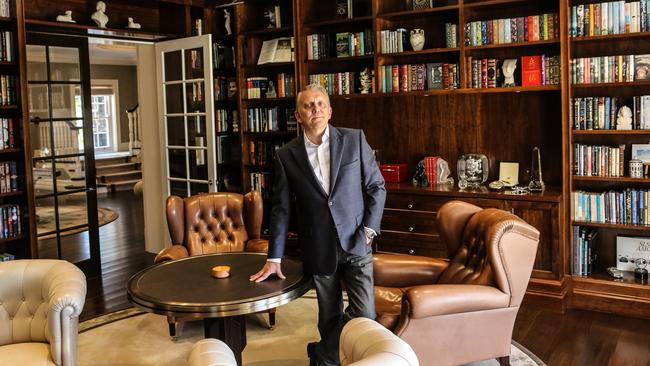

Richest 250: Pharma king Dennis Bastas reveals deal-making success

Dennis Bastas points to his engineering brain and an appetite for discomfort to explain his extraordinary deal-making success.

Dennis Bastas likes to say he has never done a bad deal. And over the course of 20 years of buying, selling and merging companies, the pharmaceutical billionaire has done plenty of wheeling and dealing.

“There’s no company I have ever acquired, there’s no merger I have ever engineered, that has not succeeded,” Bastas tells The List.

He is not bragging, but as a qualified engineer he is methodically explaining the thinking and preparation he puts into every deal – “I’m known around here for saying there’s nothing that we’re doing that doesn’t have a plan A, B, C, D or E” – and how he wants to be surrounded by executives that “make me feel uncomfortable”.

Don’t miss your copy of The List: Australia’s Richest 250 on Friday, March 24, exclusively in The Australian on Friday March 24 and online at rich250.com.au.

Bastas says he has a chief financial officer whose job in life, he feels, is to tell him the 10 different ways a deal can go wrong. Which is exactly what he claims he needs.

“I think the worst thing to do is build yourself an echo chamber,” he says. “But people feel more comfortable there. I actually want to feel uncomfortable. Every time I do a deal, I want to feel on the brink of being so uncomfortable I don’t want to do it, because then I know I’ve considered all the factors.”

That deal-making acumen is about to be tested as never before. Bastas, the co-founder of Arrotex Pharmaceuticals, Australia’s largest privately held generic drug supplier, is set to buy his partner out of that business and another, Juno Pharmaceuticals, of which he also owns half. He will merge Arrotex and Juno into a company he will fully own, one that will combine for pre-tax earnings of more than $250m and annual revenue of at least $1.5bn.

“My bankers (Goldman Sachs and KKR) are telling me this is the largest private deal that has ever been done … the largest non-private equity debt sponsored deal in Australia,” Bastas says.

“Is that a good thing or bad thing? Well I’m not sure. But it is a big business and a diverse business. And I suppose these things don’t happen by accident.”

Bastas has, after all, spent two decades doing deals. In 2003, he left behind a management role at ASX-listed microcap ISIS Communications to get into the generic drugs business after figuring Australia was a good market for the cheaper versions of the brand names pharmacies sell.

He set up Genepharm Australia with a Greek family and listed on the ASX in 2004. Bastas’s Greek partners were later bought out by Indian entrepreneur Arun Kumar, with whom he would later privatise and delist in 2009 what by then was named Ascent Pharmahealth.

Under that umbrella was pharmaceutical business that would later be acquired by US firm Watson, as well as Pharmasave and CHS, which would be bought by Sigma.

Bastas started Juno in 2013 and genetics firm MyDNA in 2015, and then acquired Arrow Pharmaceuticals later that year. All three deals were done with different partners.

Arrow later merged with the Canadian business Apotex to form Arrotex.

“I’m persistent and patient,” says Bastas. “When I know something is worth doing I will just patiently persevere and overcome the roadblocks and find the way it takes to do something. Every deal has 10 different ways for it to fail, and there’s only one way to do it. Knowing that, I just persevere until I find the one way the deal gets done.

“You have to realise that somebody has to be flexible and I accept that my role to get a deal done is to be the flexible one.”

Bastas studied engineering and industrial design at university and once had aspirations to design cars for Ford. He says that engineering mentality helps with deal-making, and also balancing the demands of being in business in partnerships until now.

“I don’t have a formal qualification in finance,” he says. “I’m an engineer … so I can look at a spreadsheet and remember every number. I have a way of connecting how the numbers work. That’s my skill.

“A lot of people say ex-engineers are good CEOs. We tend to be good problem solvers. There’s no perfect solution to a problem, and in engineering you’re taught to find the balance of all the competing factors.”

Bastas started talking about the Arrotex and Juno deal about a year ago, and has been able to get what were two separate transactions – buying out his partner in each business, and combining them into one – using “one big bucket of money at the one time, thankfully”.

“The thing about these businesses is that they generate good cash. We are not managing capital-intensive infrastructure, so it is easier to fund [a deal] this way because there aren’t big hits of capital building factories and the like.”

While he is on the verge of pulling off his biggest transaction, crucially Bastas also just missed agreeing to what would likely have been his first bad deal.

A little over a year ago, the US public markets were gripped with a SPAC (Special Purpose Acquisition Company) craze and Bastas almost joined in.

SPACs, which involve shell companies that raise money from investors and list publicly with the sole purpose of merging with a private company, were one of the hottest things among US investors in 2020 and 2021, and a popular alternative to traditional floats.

But as the technology sector in particular has cooled in the past year, the gloss has come off SPACs. Now, just about all of those SPACs have plunged in value – many as much as 80 to 90 per cent of their original float price.

Bastas’s biggest personal investment outside Arrotex and Juno is genetics company MyDNA, which was on the verge of floating on the NASDAQ exchange as part of a SPAC. “We had signed an arrangement with a SPAC and then they said well, the market conditions have changed, so we want to change the terms (of the deal). So I said, you know what, I don’t think we want to pursue this,” he explains.

“But if we were three months earlier we would have gotten the funding, done the deal, and I’d say – even though we are the only profitable genetics company in the world – I would think we still would have lost 80 per cent of our market capitalisation. So it is even more important to pick the deals you don’t do.”

Bastas says MyDNA is likely to explore an ASX listing later this year, and he is now working on that deal with Macquarie. The timing will depend on market conditions and shareholder appetite.

In the meantime, he will bed down the Arrotex and Juno merger – though he admits he has a rough plan to float that combined business on the ASX in a few years’ time. The size of that new company would likely see it placed among top 50 corporations on the ASX.

Bastas is buying out the Canadian partners of Arrotex and Juno – the two investors had separately owned 50 per cent of each business – to make one big Australian-owned firm. In a way, that makes him just about the last big Australian pharmaceutical entrepreneur, given his competitors are mostly foreign-owned multinational corporations.

Arrotex provides about one-third of all the volume of drugs to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, while Juno concentrates on supplying drugs that are used in oncology and surgery to hospitals.

Bastas has also made bolt-on acquisitions, such as the sales business Farmaforce last year.

Given the activity he has undertaken over two decades, he believes there is an art to doing a deal – and they can sometimes come about because of specific targets that he sets his business.

He says he is outcomes driven and sets financial goals for the business to hit – mostly pre-tax and financing cost profit targets – and goes all out to hit them. That led him to making the Arrotex deal happen when he realised the business as a stand-alone entity wouldn’t hit his profit targets.

“I try to break things down and when we are doing things that don’t help and it looks like we won’t get there (to the profit target), I intervene,” he says. “So there was a point when I realised with Arrow that we weren’t going to get there and so that’s when I proposed the Apotex deal.

“Maybe three or four months earlier, I’d met their CEO. I then called him out of the blue and said ‘listen, I’ve got a proposition for you’.

“But the catalyst for that call was the realisation that there was no organic intervention that was going to get me to the goal I’d set.

“I could have sat there and said ‘well I have to change my goal’. But that’s not how I operate. And that’s why I embarked on that journey and that’s the same with the goal I’ve set with (Arrotex and Juno).”

Bastas smiles when asked what specific financial target he has in mind for the combined business, but he’s not saying.

He does add, though: “I’m pretty certain that with the assets we’ve got we’re going to get there. But there’s a chance that some of these things aren’t going to grow as fast as I want them to. That might require intervention and … I might have to do a bolt-on acquisition or something like that.”

Arrotex last year bought sunscreen business Sunlife Holdings, skincare products brands MyAura and Brutal Truth, and 50 per cent of MCo Beauty as part of Bastas’s plan to expand into the health and beauty markets.

Given his passion for deal-making, there is irony in the fact that none of the transactions that Bastas has pulled off in two decades would have happened if he hadn’t squeezed better terms out of a deal he made with his wife – and also not gone to work for one of Australia’s biggest and most famous companies.

“We had a small townhouse we had paid off. No mortgage. My wife and I decided I would take the risk, have a crack. I went 18 months before I drew an income – and that was probably six months longer than my wife wanted!

“We were living off a line of credit; that’s what kept us going. My wife kind of said, ‘12 months and you have to go back (to an executive job) and attend a few interviews’, but I had this desire to be in charge of my own destiny.”

Bastas had previously worked for Coles Myer and Village Roadshow in executive roles, and went on to interview for a senior executive position at BHP, to build the mining giant an e-commerce platform. He had a job offer, but there was a holdup and he couldn’t start for three months.

“But I got some investors in and everything came together at that time,” he says. “I said (to BHP), I’m moving on and what I’ve started is under way. And that was it.”

Bastas says he can think of at least three occasions subsequently when his businesses came close to shutting down. A deal, new contract or acquisition would get him out of trouble and growth would eventually continue.

Today, his biggest challenge is taking on the big multinationals he competes with in Australia. He says if he wants to grow at 15-20 per cent annually in an industry with organic growth of a couple of per cent, then his business has to take market share from others.

There’s also the potential to move into overseas markets.

“I want to keep this owned by Australians though,” he says. “It would make sense that investors know they are buying our products during cough and cold season, when they’re managing their cholesterol or diabetes.

“And one day it makes sense for it to be publicly listed. And by the time we do that, there probably won’t be a household in Australia that wouldn’t have one of our drugs in their medicine cabinet. (People) just don’t know that now. They will.”

The 2023 edition of The List – Australia’s Richest 250 is published on Friday in The Australian and online at richest250.com.au.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout