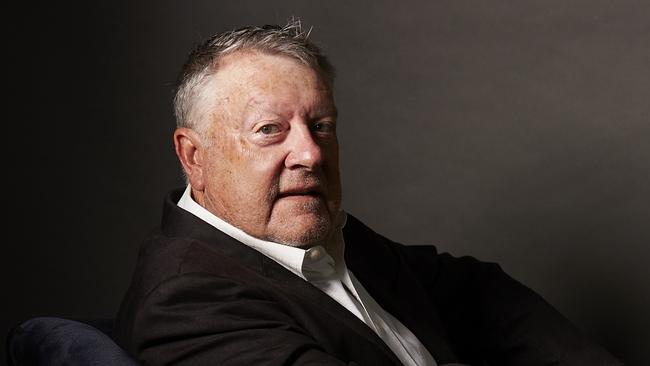

Rod Duke: From shoes salesman at 16 to retail billionaire

An impatience with school that turned into a dogged commitment to learning the retail game led Rod Duke across the ditch, where he made himself a fortune.

Rod Duke’s path to becoming a retail billionaire started with a simple premise.

“I’ve always loved the idea of buying something, selling something and making money on the way through,” he says. “I’ve always had a real attraction to that.”

The low-key, Australian-born business mogul has spent decades across the ditch building up one of New Zealand’s biggest retail chains, Briscoe Group, and in the process amassing a $1.1bn fortune. All from a company he bought for just $2.

While little known in Australia, Duke is now an established member of The List – Australia’s Richest 250, the 2023 edition of which is published by The Australian on Friday, March 24.

Duke he says his hunger for success can be traced back to an inauspicious start selling shoes at the Rundle St, Adelaide, branch of retailer Ezywalkin.

Don’t miss your copy of The List: Australia’s Richest 250, exclusively in The Australian on Friday, March 24 and online at rich250.com.au.

After watching his father work as a real estate agent and bookkeeper at the races, Duke called time on school at 16 and decided he was better off working the shop floor.

“It just seemed to me back then that I was wasting some valuable time,” he says. “I wasn’t a spectacular student, but I was very adept at working long hours.”

Even on his days off, Duke turned up at the store to sell shoes. And on a Friday night he’d double up, washing dishes for $20 at a local restaurant rather than sitting in the pub.

From the start, he trusted his instincts.

“I’ve always considered myself a person who can relate and speak to people very, very easily; I don’t have any problems. I’m a fairly gregarious guy. I’m a listener, and I care about what people think and what they say. It just seemed to come naturally to me,” he tells The List from his Auckland office. “My father was the same. It was in the family.”

Two years in, Duke was Ezywalkin’s top seller, managing the chain’s third biggest grossing store by the time he was 18.

He then spent formative years working for some of Australia’s most storied department store dynasties. His journey in retail started with Adelaide department store John Martins – known as Johnnies and later bought by David Jones – before a move to the bright lights of Sydney. There he joined Waltons, later sold by Alan Bond in 1987.

He then jumped to Grace Bros, but when that was swallowed by Myer he rejected a move to HQ in Melbourne. Instead, he joined the late David Cookes’ retail empire, where he was handed the job as managing director of resuscitating Norman Ross, a predecessor of Harvey Norman, which was losing up to $40m a year.

After stemming the losses, Duke got a call that was a little left-field but he found hard to pass up. It was September 1988, and a headhunter had noticed his turnaround work in Australia. They wondered if he might take on some consulting work in New Zealand fixing up a small wholesaler called Briscoe Group.

Duke’s brief was to find a buyer for the ailing home goods operator, land a commission, and then head back to Australia. Under its Dutch owners Hagemeyer, Briscoe had ambitiously taken on the switch from a wholesale operation to creating a string of nationwide retail outlets.

Duke ended up buying the company himself for just $1, and officially took control on January 1, 1990. “It was a very nominal sum. You don’t expect to pay a lot for a company losing $2m a year,” he notes dryly. The total outlay doubled to $2 when he acquired the last share a decade later.

Asked for his first impressions of New Zealand when he arrived there in the late 1980s, he takes a deep breath: “Look, it would be wrong to say it was backward. But it would be right to say I’d had all these experiences some years before in Australia.”

Duke immediately set about testing the Kiwi market.

“First I thought, OK, I wonder if they carry any baggage. So I paid a lot of money for survey work with the general public. Just anonymous survey work. Have you heard of this company called Briscoe? What exactly do you know about them? And in a very, very short period of time, I was convinced that the company did not carry any baggage.

“Nobody said ‘I hate shopping there’. In fact a lot of people said ‘my uncle worked there and my mum shopped there’, and (asked) if they were still around. So quite quickly I realised it was a company that had been lost and forgotten rather than being disliked. For me it was about resurrection rather than reinvention.”

Duke gathered his 10 senior staff in Auckland and laid down the reality of the situation. “Before we go home today, we have to figure out where this business goes,” he recalls saying, “because I can’t stay where I am and make a living.”

The 2023 edition of The List – Australia’s Richest 250 is published on Friday, March 24 and online at richest250.com.au

Duke knew the Bunnings colossus was about to land – its first warehouse opened in Melbourne in 1994 – so immediately decided against construction and hardware.

Next on the list? Toys. A good money-spinner, but in Duke’s eyes a 30-day business that only delivered once a year. It was also gone.

Instead, he settled on the housewares business, with the pitch of selling famous brand names at a cheap price.

Duke’s extensive time working in Australia’s cutthroat retail world was about to come in handy. He knew there would be a market for established brand names at a reasonable cost and decided not to try to compete with the big-box Warehouse stores, a rival that had opened a decade earlier and was best known for selling rice paper blinds.

“They were selling knives and forks from Mongolia. It wasn’t our bag,” he says.

Duke had controlled electrical appliances working at Grace Bros, and he tapped those same contacts to start opening up a big trade route from Asia to New Zealand.

Briscoe only had 12 stores, and as leases expired it sought out new locations that could serve the masses.

“The dream, of course, was to grow the network to its maximum number, and I didn’t have in my mind what might be an excellent number, because I knew that the store development program – once you finished and you did the rounds – you’d have to go back to the first store because suddenly it was bigger, or needed to be relocated. So that job, even today, is still not finished,” he says.

“But I’m convinced that if you want to be in the retail business, you have to be number one or at the very least number two in the categories. You’ve got to be really, really powerful in the categories you’ve got. Secretly, I always wanted 100 stores. And I’ve got nearly 100 now.”

As he assembled homewares merchandise, Duke also spotted a gap in the market: becoming the first retailer to open on Sundays, despite that being still classified as illegal in the country. “I’m always looking for ways I can do something a bit different,” he says. “Something that makes people stand up and say, oh wow, I never thought of doing that. That’s pretty clever.”

He paid staff overtime and encouraged them to volunteer to work on Sunday, wary about any charges of forced unionism. After years of being hemmed in by archaic laws, shoppers flocked to Briscoe stores, with tellers ringing up an entire month of sales every single Sunday.

“Every week you’re on the front page of some of the local papers. People were talking about the television news, and there was this idea that it was a bit off the wall and I’d better go and have a look,” Duke remembers.

“Well, we promoted six consecutive Sundays before the government quickly passed legislation in the parliament to make it legal.

“We didn’t get fined. All the staff volunteered. And I did about six months’ worth of trading in six single days.”

Part of the secret of Briscoe’s gradual success was finding its market sweet spot. A jingle for TV advertising was created – “Briscoe’s you’ll never buy better” – that seemed to strike a chord with customers.

“We didn’t want to say discount or cheap,” Duke says. “It just means better quality, better value, better service. It means slightly different things to different people.”

By 1996, Briscoe was “very, very profitable”, giving Duke the confidence to expand again and create Rebel Sports.

“We saw a gap in the market in this country,” he says. “We decided to build 2000sq m – half an acre – with everything. Tennis racquets, all the big brand names, all the shoes and all the apparel. And from the moment we opened the first one it was just abundantly clear that this was going to be a very, very powerful category for us as well.”

By 2000, Duke had acquired the intellectual property and rights for the Rebel name in New Zealand. But in wealth terms, it was the decision to tap public markets with an IPO that proved to be a master stroke.

Briscoe listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange in December 2001 with a market value of just $NZ210m, in the same ballpark as jeweller Michael Hill but just a tenth of The Warehouse’s $2 billion value.

Twenty-two years on, Duke’s 77.1 per cent shareholding is worth about $750m and the company’s annual revenue of $NZ785m outstrips The Warehouse – founded by one of NZ’s richest men, Sir Stephen Tindall – by hundreds of millions.

The two retailers are often cast as rivals and Duke concedes that a competitive streak is hard to shake.

“They went through five managing directors very quickly,” he says. “I suspect there’s something in there that MDs find it very, very hard to get on top of, and think through and execute. And to be honest I’m just not close enough to it. Quite frankly, if I knew the answer, I probably wouldn’t tell you anyway. I want them to continue to struggle.”

Duke says part of his success in the past two decades since the IPO has been the result of decisions he didn’t make. He cites e-commerce, where Briscoe trod carefully in the early dotcom boom days.

“From my experience, it actually costs a lot of money to be an early adopter,” he says. “Because technology changes, and every time it changes it costs a lot of money. So we were late to the party. But when we did arrive and commit, it proved a godsend.”

Some 20 per cent of Briscoe’s sales are now online, but Duke remains a fan of the physical retail store.

Each morning he receives an email with the vital stats: sales by store, by brand, by revenue by store, by margin, by store by group compared to forecast and budget.

“I still make phone calls when I get them,” he says. “What happened at Wanganui yesterday? I still do a bit of that. But I’m not quite as obsessive or as focused on store performance as I was 25 years ago.

“I can’t resist getting on the shop floor. And I’ve been sent away from the shop floor many, many times. My operations boss keeps telling me, you are the most expensive shelf sorter in the company. It’s just in your blood. You can’t walk past something when it’s wrong without spending 30 seconds and getting it right.”

Duke is now aged 73, and questions are being asked about his next move. And what he’ll do with that enormous shareholding. His adult son is entering construction, ruling out any succession plans. Still the MD, Duke is relaxed and shows no sign of stepping back just yet.

“I think now, for the remaining period of my working life, I’ve really got to find a way of transferring all the years of knowledge in this retail business to one or two or more people inside this organisation. So they’re well prepared to take on either my role or a similar role, so I can play golf three times a week.”

And as for the near $1 billion stake?

“I haven’t got a hang-up about how many shares I own. At the end of the day I don’t mind having 62 or 59 per cent. Having said that, I’d love to hang on to 51 per cent if I could,” he chuckles.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout