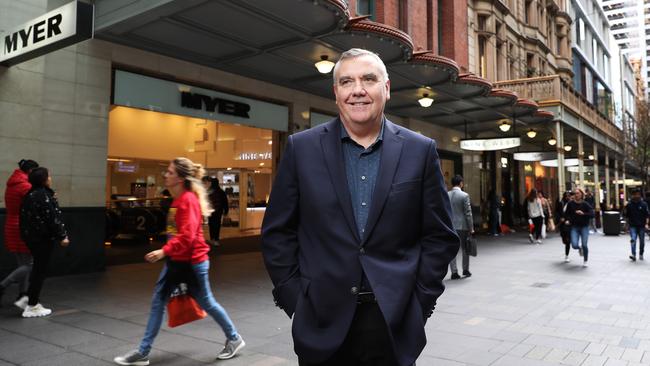

Retail veteran Bernie Brookes calls on Myer, David Jones to merge

The one sure way for Australia’s department stores to save themselves is to join forces.

There’s one sure way to save Australia’s venerable department stores, David Jones and Myer: end the retail war and join forces.

That’s the view of retailing veteran and former Myer boss Bernie Brookes, who says the two department store operations must merge to escape a “doomsday spiral”.

From millennials who view department stores as old hat through to office workers’ growing preference for a more casual fashion look, shopping trends are swinging against the retailing duo who have duked it out for decades.

“There are about 100 department stores in Australia and the viable level is 50 to 60 department stores,” Mr Brookes said.

“Not only should they halve the number of stores but they should also halve the space of the stores. The only logical way the two of them will get returns for their shareholders will be to bring the two businesses together.”

Mr Brookes, who was chief executive of Myer from 2006 to 2015, pushed for such a radical move five years ago but the-then owners of David Jones rejected the proposal.

Since then, the profitability of department stores in Australia has halved, with David Jones writing down the value of the company by $437m due to what it called a “retail recession”.

“If you had one head office, one buying team, one operations team, one visual operation team you would be able to save between $50m and $80m a year, instead of having two of everything,” he said.

The two brands could still exist, but Myer could close stores in upmarket suburbs while David Jones scales back in lower-income areas.

Mr Brookes also said he believed DJs was making a mistake by expanding its once-famous food hall offering. “There has been a food miscue at David Jones,” he said. “They will pay the price of it for many years to come.

“There has been an overcapitalisation and an over-expenditure in the stores (on food) with expensive fixtures and fittings which won’t give a return. Food for David Jones is definitely a no-no.”

He said department stores were now mainly focused on fashion, accessories and cosmetics as other product lines such as electrical appliances were being sold more efficiently by Harvey Norman and JB Hi-Fi. Other goods such as manchester and homewares could be bought cheaply online.

In the fashion stakes, the stores were under pressure from competitive overseas retailers setting up in Australia such as H&M and Zara and the increasing popularity of online shopping.

“The route to market by some of these big brands, which was once exclusively through department stores, has now changed significantly,’’ he said.

“It is direct to the customer through websites and free-standing stores.’’ They are going direct to the customer and not working through the department store concessions.”

Mr Brookes said the answer was to develop private labels that were exclusive to the department stores, but this was a long-term strategy.

He said many younger consumers didn’t like shopping in department stores, leaving them to appeal to an older, more conservative demographic. “The department stores are not on the agenda for the millennials,” he said.

The casualisation of clothing in Australia had also reduced demand for the high-end clothing sold in department stores.

Mr Brookes said department stores were facing a “death of a thousand cuts” as they continued to slowly cut store numbers, putting the companies in a “doomsday spiral” of lower productivity and cost-cutting.

Big name retailers overseas such as Macy’s, Dressbarn, Pier 1 imports, Gap, JC Penney, Abercrombie & Fitch, Topshop and British retailer Debenhams, were all undertaking major store closures. US retailers announced the closure of more than 7000 stores in the first half of this year.

“In the US and Britain and now in Australia, we are seeing people realise that less is best, rather than more is best,” Mr Brookes said. “It’s a space race — how do you get less space quick, how do you get a fewer number of stores quick.”

Mr Brookes said he did not think the merger proposal was being discussed by either of the stores but “they still should do it”.

He said both Myer and David Jones were run by two experienced retail executives who were unable to take the plunge and make big store closures needed to improve the viability of their businesses because they were tied up with long-term leases with shopping centre owners.

He said major store closures would also force more writedowns and see the chief executives face heavy criticism from investors.

“The problem is the inability to take the medicine because of pressures from shareholders and the market who would rather have death by a thousand cuts,” he said.

“Both Ian Moir (chief executive of South African company Woolworths who led the $2bn takeover of DJs in 2014) and (Myer chief executive) John King, have announced a reduction in space,” Mr Brookes said.

“We have two really good retailers running both businesses. “They understand what is going on. The problem is they are at the whim of the shopping centre owners who have them entwined in long-term leases, and they are at the whim of the market which won’t allow them to take the decisions necessary to take more significant writedowns on their business and right-size their number of stores.

“They are getting less productivity, less volume, the percentage cost of their rent is going up, and the reaction is to cut marketing budgets, and to cut wage budgets.

“So it becomes a doomsday spiral when the answer is to cut stores and cut space.”

Mr Brookes admitted that he had made a mistake when he was chief executive of Myer in continuing to open new stores.

“Department stores continued to open stores, even in my time, which was wrong,” he said. “We should have stopped opening new stores a lot earlier than we did.’’

After leaving Myer at the end of 2015, Mr Brookes went to Johannesburg for almost three years where he ran South Africa’s largest non-food retailer, Edcon, which he saved from near bankruptcy.