What Sydney, Melbourne can learn from New York City planning

Melbourne and Sydney, our two Australian giants, are quickly approaching the population of current day New York.

Melbourne and Sydney, our two Australian giants, are quickly approaching the population of current day New York.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Melbourne will reach New York’s 8.6 million residents by 2051. Sydney follows three years later.

Melbourne and Sydney are already important nodes in the global city network.

The Globalisation and World Cities Research Network at Loughborough University in Britain ranks Sydney in the top 10 most globally connected cities. Melbourne makes the top 30.

With two Australian New York’s by the 2050s we need to see what we can learn from the Big Apple about urban planning.

From first colonial settlement in 1624 by the Dutch, New York was a globally connected city.

New York always accepted its future was urban growth, that it was international by nature.

Even though money was often tight (New York was frequently close to financial ruin) and the city had racial problems, very ambitious public works projects were regularly commissioned. New York always aimed high.

In Australia, many are still hoping our cities will stop growing and think traffic congestion and housing affordability can be solved without massive new infrastructure investments.

The clock won’t be turned back — Sydney and Melbourne are well-established parts of the global city network.

The network of global cities needs English-speaking hubs in Asia and this won’t change in the foreseeable future.

We need to invest in our cities to prepare for our New York-esque future. Urban growth, if done right, leads to vibrant, creative, beautiful and desirable places to live. Let’s see what we can learn from New York to create such places in Australia.

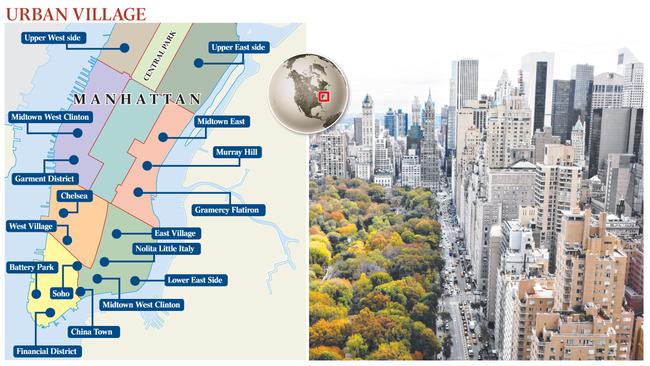

New York is made up of five boroughs. The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island and Manhattan. Manhattan is the most famous — it’s where the jobs are clustered, particularly in the area south of Central Park (Midtown) and in the financial district at the southern tip of Manhattan.

It’s the equivalent of the CBDs of Sydney and Melbourne.

Many workers commute to the Manhattan job clusters from far away using the rail and road network. That’s the same in Australian cities. But New York wouldn’t be able to cluster so many jobs in Manhattan had it not also managed to house many workers in Manhattan itself.

This is something we haven’t done to scale in Australia. We will need to get this right with Melbourne and Sydney.

In the context of urban planning in Australia, we talk about the missing middle. The term describes an area of medium density dwellings near the job clusters (let’s say a 10km radius around the CBD). In our Australian cities this area is largely absent.

Let’s look at New York, where the West Village and the East Village are the most attractive residential locations.

Located between Midtown (Time Square) and the financial district (Wall Street) these neighbourhoods are exactly what we are missing in Australian cities.

Here are mixed-use (shops and eateries on ground level and residential above) neighbourhoods with five-storey buildings, quiet streets, one-way traffic roads that allow lots of room for cyclists, parks and a socio-economically diverse population (more about rent control later).

Melbourne and Sydney in the 2050s will very likely still cluster jobs, especially the high-paying ones that attract global knowledge workers, in the CBD.

Melbourne and Sydney must aim to house more workers close to these jobs to minimise the stress on the transport network.

At the same time, the public transport network must be expanded. New York’s famous subway links the four surrounding boroughs to the job clusters in Manhattan. Digging tunnels for a subway of the scale of New York is only financially viable once the population density is high enough.

Remember, tunnels are costed per kilometre. We will see the arrival of subways in the coming decades in Melbourne and Sydney — building them earlier rather than later will be cheaper.

Public transport alone isn’t enough to manage traffic in our emerging Australian New Yorks.

Most of the roads in Manhattan have been transformed to one-way streets. Rather than making two lanes available for cars, New York provides generously sized bike lanes. Public transport and bicycles coexist peacefully in a well-integrated transport network.

New York’s bike share program (Citibike) has docking stations across the whole city — not just in the inner city. For an annual fee of $US129 you get unlimited access to these bikes.

Like Melbourne and Sydney today, New York is faced with big housing affordability challenges. This will only be amplified once we add three million more residents to our cities. What can New York teach us here?

There are still plenty of middle and low-income earners living in Manhattan, due to strict rent control. Under the Mitchell-Lama Housing Program, New York acted as developer for rent-controlled apartments and makes them available to middle and low-income earners.

This allowed a diverse mix of people to live in Manhattan.

Replicating a similar housing scheme in Australia will require a rethinking of the role government plays in the housing sector.

Whatever the mechanism, Sydney and Melbourne would be well-advised to increase the number of residential dwellings near the CBD. Without rent control everyone but the highest income earners will be pushed out, resulting in a city segregated by income.

Another factor for the high liveability of the suburbs of New York are the countless public parks, sporting fields and plazas.

New York has had lots of strong personalities in positions of power who pushed hard for major projects — the establishment of green spaces is a recurring theme.

New York is still building new parks and works hard to green its streets. Our big cities need big bold urban greening developments to increase liveability and decrease heat-island effects.

This is not a simple call, to hand over our cities to big builders. The big building projects in New York were routinely balanced by citizen-led movements.

The most famous example was when urban activist Jane Jacobs opposed Robert Moses’ plan to bulldoze medium-density communities in Lower Manhattan to make room for a massive highway.

In Australia we need to come to terms with urban growth. Our country will soon be home to two cities the scale of New York and we need to plan and build accordingly. To make these cities liveable we must create our own Australianised version of the Big Apple.

Melbourne and Sydney will look and feel different but hopefully will have drawn inspiration of what makes New York the quintessential global metropolis and one of the world’s most desirable urban destinations.

Simon Kuestenmacher is director of research at The Demographics Group.

simon@tdgp.com.au