Over the past few decades the Australian workforce shifted away from so-called middle skill jobs to highly skilled jobs. Along with this, our cities changed too.

Manufacturing is the archetypal middle-skill sector. In 1985 manufacturing was the largest of the 19 official Australian industries, providing employment for 17 per cent of all workers (1.1 million jobs). Today, manufacturing is only the eighth-largest industry and employs less than 7 per cent (857,000).

The shift from middle to highly skilled work started in the 1980s and is continuing today. Data from the census shows that this change even sped up.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics assigns each job a skill level. Jobs that require a lot of university study (for example doctors and engineers) are ranked as skill level 1, typical blue-collar jobs (such as manufacturing and trades) are ranked as skill level 3, while jobs that require no formal training (such as cleaners and cafe workers) are ranked as skill level 5.

In the past five years almost half of all net new jobs (46 per cent) were skill level 1, while only 1 per cent were middle-skilled.

These changes in the DNA of the workforce affect the structure of the nation’s cities and affects the sentiments of Australians.

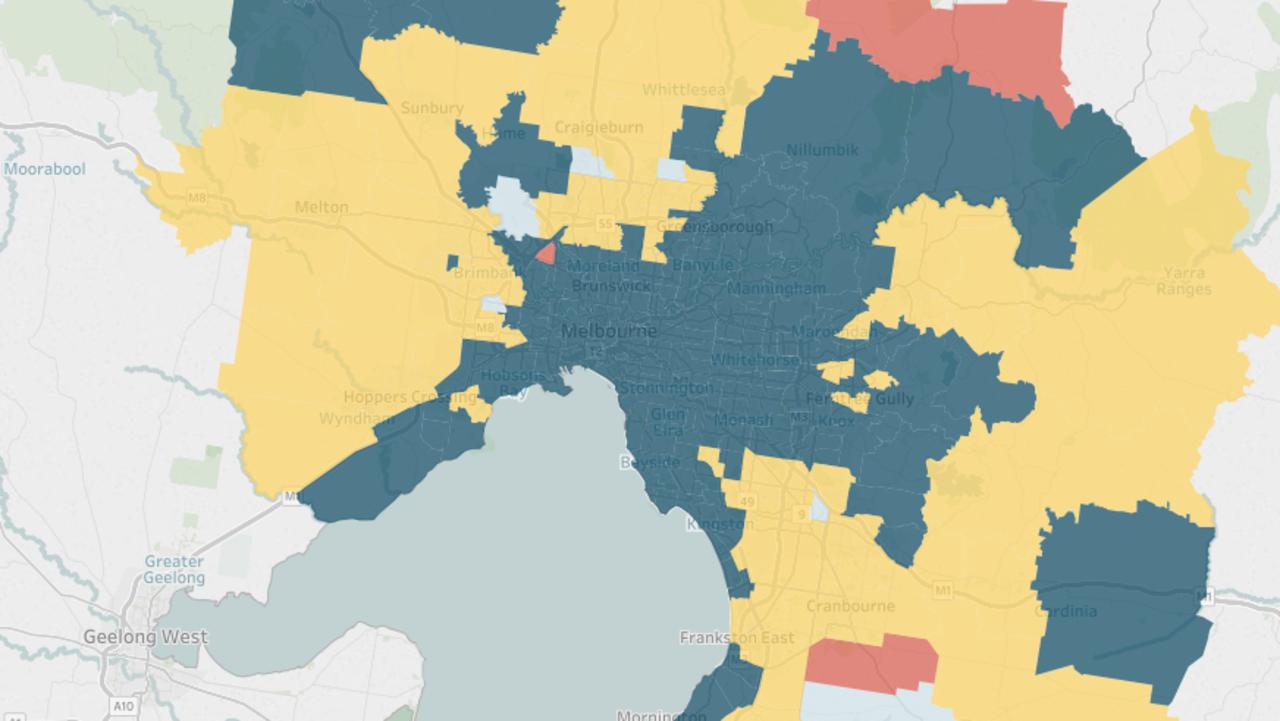

For starters, skill level 1 jobs love to cluster. Knowledge workers benefit from working close to other knowledge workers. This is why we’ve seen so many office towers pop up in the central business districts of our largest cities.

Regional cities often miss out on job growth because the type of jobs that the economy produces (remember that 46 per cent of net new jobs were skill level 1) are created by businesses in CBDs.

The well-paid workers in these towers want to live close to work. The more our cities grow, the larger this desire becomes, and workers pay a premium for housing close to work to avoid commuting.

Density in inner suburbs is a result — sometimes with smart, medium-density buildings using the latest environmental standards that are well-integrated into the urban landscape; other times with cheap and ugly shoebox-apartment towers.

In either case, the inner suburbs become more expensive (in a free market we expect exactly this to happen) and the poorer middle and low-skilled workers must find housing in the outer suburbs, increasing their daily commute.

All inner and middle suburbs, of course, are home to many low and middle-skilled workers. As prices have been increasing in recent years in these suburbs, the new workers had to seek accommodation further away.

Meanwhile the low and middle-skilled residents who have lived in these suburbs for many years also feel the pressure of the increasing housing costs. Their parents could afford to live in these suburbs, and did a decade or two ago. But now that everything has become more expensive, and while middle and low-skilled wages haven’t grown much, these workers rightly feel frustrated.

The shift towards knowledge work, the increasing mechanisation of agriculture and the slowing mining sector had led regions to look enviously at the population and job growth in the big cities. Individual middle and low-skilled workers in the capital cities feel they miss out on the benefits of economic growth.

To be clear, the frustrations of business councils and mayors in the regions fighting to attract jobs are real. So are the pains of the low and middle-skilled city dwellers.

How should we deal with these changes?

I’ve mentioned that we aren’t creating new middle-skilled jobs in Australia. If you came of age in the 1970s and 1980s in an Australia heavily dominated by manufacturing jobs, it would be hard not to bemoan a time when a middle-skilled job could comfortably feed and house a family. Nostalgia, however, won’t change the composition of the workforce today and into the future.

It’s easy to provide advice to individual workers on how to navigate today’s labour market. Lifelong learning, consistent upskilling and an awful lot of grit are the main ingredients for success. If you add proactive networking, maintenance of close friendships and a good dose of the Australian “she’ll be right”, workers should be able to succeed professionally.

Youth will benefit from higher education and being team players (don’t rob your kids of the learning opportunity provided by regular losses in sport). A university degree is always a good move but as long as Australia keeps growing, jobs in healthcare and construction should be safe, too.

It’s much harder to advise on systemic changes. The global economy, our national labour market and Australian cities are highly complex and interconnected systems.

Housing in the inner suburbs won’t get more affordable while we keep adding more and more skill level 1 jobs to the CBD.

If we were to spread out jobs more evenly across our cities to secondary CBDs (the urban planning strategies of Melbourne and Sydney propose just that), the suburbs surrounding these areas would go up in price while traditional inner suburbs would see price pressure ease a bit.

In the US, take San Francisco for example, it’s quite common for head offices to be decentralised in suburban office park locations often 30km-40km from the CBD. There is some evidence of this occurring in Sydney and Melbourne at West Pennant Hills, Norwest Business Park and at Tally Ho. But these are the exceptions. In the US, businesses and consequently highly skilled workers spread out more because regions compete by offering low corporate tax rates and other goodies.

Without serious government intervention, I expect the current trends to continue in Australia. The economy will continue to create highly skilled jobs at a much higher rate than middle-skilled jobs. These jobs will cluster in the CBDs of the capital cities.

On a planning level, further efforts should be directed towards building knowledge work enclaves in major regional cities such as Geelong (for example, the NDIA head office), the Sunshine Coast (with its new Sun Central CBD) and Newcastle (on the Honeysuckle site).

In a world in which social cohesion becomes an important political imperative, perhaps we should be looking at ways of not just reducing income inequality but also of mixing up jobs so that every part of every city has reasonable access to skill level 1 jobs.

Maybe it’s up to individual business leaders to relocate their skill level 1 jobs to places such as Parramatta, Box Hill, Chermside, Tea Tree Gully and Joondalup. Helping to establish more high-level jobs in decentralised location is one way individual businesses can help to foster better and stronger urban communities.

Simon Kuestenmacher is director of research at The Demographics Group.