Covid’s ground zero: Outlook for Melbourne and Sydney property

The pandemic has changed the way of thinking about our biggest cities. Our priorities and our property requirements are being reimagined.

It isn’t a case of getting back to normal. We have come to realise that the old normal was flawed. We are questioning commuting. We now understand the folly of relying so heavily on access to foreign labour. We are looking to broaden our supply chains. Our priorities and our property requirements are being reimagined.

The allure of the inner city’s apartmentia has been dulled by the advent of work from home. A chic minimalist apartment doesn’t stack up against spacious suburban (or treechange/seachange) property if there are kids and parents now working from an at-home Zoom room.

Supply chains inextricably connected into China are now considered (by some) as a problem; there’s an urgent need for local manufacturing, and for warehousing and distribution facilities. (You really know a property segment is on the move when the common “warehouse” gets a flash new name: these facilities are now known as “fulfilment centres”.)

Flight of long-term visitors

The Australian property market is underpinned by an array of rising forces driving demand, namely a relatively strong birth rate (1.8 births per woman) and relatively high levels of net overseas migration (263,000 in 2017). The latter figure is comprised of skilled immigrants (plus others on humanitarian grounds) as well as foreign students and backpackers.

Before the pandemic the foreign student population in Australia was roughly 600,000, with a portion of these students graduating and returning and others arriving every year. As more have tended to arrive than depart, over time the aggregate number has risen. It is this market that has piqued demand for inner-city rental accommodation.

I am assuming that backpackers have tended to gravitate to tourist hot spots, perhaps working as waiters in Noosa and Cairns. Many backpackers, along with seasonal workers from the Pacific Islands, help Australian farmers with the harvest.

But the coronavirus changed the demographics of this transient workforce. In June last year, Australia’s overseas-born permanent resident (here for no less than 13 months) population numbered 7.5 million, or 29 per cent of the total population.

This proportion is roughly double the equivalent figure for the UK, for Germany, for the US. The proportion of immigrants and other long-term residents in China and Japan is less than 2 per cent.

Over the two years to June 2021, Australia’s overseas-born permanent resident population dropped by 30,000. This was the Covid-inspired upshot of foreign students and backpackers going home versus expat Australians coming home.

The biggest losses over this period were from China (down 72,000), the UK (down 23,000), Italy (down 11,000) and New Zealand (down 8000). The Indian population jumped by 46,000. The Filipino population increased by 15,000. And the number of Nepalese increased by 11,000. Some of this growth would have occurred in the 2020 financial year before the border closures in March.

No doubt much of these flows would have involved students and backpackers going home. However, other losses would result from the ageing process as older Australian residents born in the UK and Italy, for example, sadly, die off. I reckon the Kiwi exodus can be at least partly put down to the “Jacinda effect”.

During the 2021 financial year, net migration to/from Australia was a net loss of 89,000, which compares with net gains of 192,000 the previous year and of 241,000 for the year before that.

Border closures converted a long-term net migration gain (say, 240,000 a year) into a net migration loss (say, 90,000), which has resulted in a net loss of 330,000 potential workers in the 2022 market.

I reckon that’s more than 1000 A380 planes jam-packed with students, immigrants and backpackers that Australia needs simply to get back to the levels of the pre-Covid labour pools.

Impact on Melbourne and Sydney

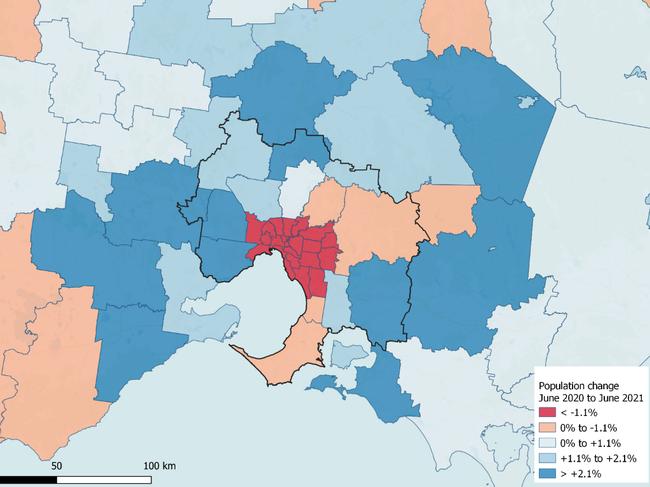

The biggest impact of the loss of immigrants and others has been felt in Melbourne.

Data recently released by the ABS shows there was a net reduction in the estimated resident population of all Melbourne municipalities extending between Brimbank and Maroondah. Indeed such was the student exodus in this year that it offset any natural increase in these municipalities.

It’s almost as if the student, the backpacker and perhaps some skilled immigrants who wanted to return home amid a global health crisis were spread evenly – a bit like butter on toast – across the (central) metropolitan area of Melbourne. More or less all parts of the (central) city were exposed to population loss and to a diminution in demand for rental property.

But there’s something else about the 2021 exodus: it didn’t apply to the city’s lifestyle regions offering cheap house and land packages or to the city’s seachange/treechange options.

Despite the population dropping across Melbourne in the 2021 financial year, it jumped by more than 2 per cent in Wyndham, Melton, Moorabool, Mitchell and Cardinia, as well as along the Surf Coast and the Bass Coast and in city-edge Baw Baw.

This is the famous, or infamous, flight of the VESPAs, or Virus Escapees Seeking Provincial Australia, where access to lifestyle space suddenly becomes important.

Plus, access to work from home, enabled I might say by the NBN, has further driven this city-escapee movement into a kind of Goldilocks zone extending up to 150km from the Melbourne CBD.

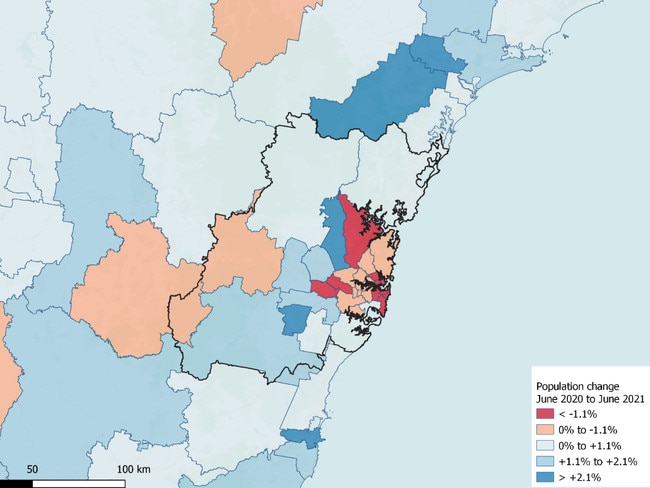

The pattern for Sydney during the 2021 financial year follows the Melbourne trend but clearly off a less affected base. There were net losses in the population across the eastern suburbs, in Hornsby on the north shore and in Cumberland and Fairfield in the west.

There was strong growth in The Hills shire as many Sydneysiders sought out the serenity, and the salubrity, of Sydney’s city-edge suburbia. Beyond metropolitan Sydney, places such as Cessnock added more than 2 per cent to its population base in this dreadful Covid year.

The struggle for supremacy

But there is more to this story about the measurable impact of Covid on Australia’s two largest cities. It raises the tantalising question of whether an event of this scale can alter each city’s trajectory. Maybe Covid has had such a disproportionate and deleterious impact on Melbourne that Sydney will race ahead during the 2020s?

Melbourne snared from Sydney the title of largest city on the Australian continent in 1858 as gold underpinned the Victorian economy. At Federation, Sydney wrested back the lead and for the whole of the 20th century it was Sydney that added more people than Melbourne every year.

That is, until the 2000 Olympics.

It’s almost as if Sydney was exhausted by the whole Olympics process, because Melbourne surged and began closing the population gap. Not even the Global Financial Crisis (in 2008) could stop Melbourne demographically stalking Sydney. Soon a narrative took hold: Melbourne would regain the title of largest city by 2030 or thereabouts. Sydney pretended not to notice its southern rival’s outrageous aspirations.

And what’s more, Melbourne’s logic was actually quite sound. Melbourne offered more people access to a better quality of life via more affordable housing in comparison with Sydney.

But Covid has hit the southern capital hard. Across the 2021 financial year, the city lost 60,000 residents whereas it usually added, say, 110,000 or more.

Sydney faltered too, but not as badly. Maybe Sydney will recover quickly, gain momentum on its southern rival, and garner more skilled workers, more flight connections, more infrastructure funding than wrong-footed pandemic-ravaged Melbourne?

Unlikely, I think.

In the immediate post-war era it was Germany and Japan that was rebuilt to modern standards after the devastation of war. The victor, London, faltered, struggled, for decades; London may have been the victor but there is something remarkably galvanising, and modernising, in the process of recovering from utter devastation.

Plus, with so many businesses to be rebuilt in Melbourne, maybe – as was the case in Tokyo and Berlin after the war – it presents the city with an opportunity to rethink businesses and the narrative of urban life entirely. New buildings in Tokyo were rebuilt to earthquake standard. Berlin’s post-war Potsdamer Platz was boldly, glitteringly, reimagined.

And therein lies the task, the role, the nation-building opportunity for the property industry.

Out with drab warehouses. In with spacious, newly conceived logistics (sorry, “fulfilment”) centres. Out with inefficient call centres; in with data centres and more common acceptance of apps to facilitate customer dealings with businesses.

Out with high-rise office towers comprised of chicken-coop work stations; in with light-filled campus-style buildings and/or flexible workspaces for training, learning, upskilling, for lectures from visiting experts, for communal collaboration spaces in which to work, to chat with colleagues, to entertain (and schmooze) clients.

Here is Covid-affected Melbourne’s opportunity to seize the initiative, to work closely with the property industry, and to rebuild a better version of the city that was left behind.

Conclusion: a role for property

Sometimes out of adversity there comes the steely determination to rebuild, to recreate, to demonstrate that a place, a city, a nation is not defeated but is rather spurred into action.

Let that be the pathway forward. And let the worst-hit city, Melbourne, as evidenced by the sea of red population loss, lead the way.

Bernard Salt is founder and executive director of The Demographics Group; data and graphics by co-founder and director of The Demographics Group Simon Kuestenmacher

The coming of the coronavirus, its mutants and its variants over the last two years has changed Australia.