A rising and rich nation: A data story of Australian prosperity in the 21st Century

Australia will soon be a top 10 economy – and we’re already the third wealthiest per capita.

And while I am sure this is important for all kinds of strategic decision-making, I am more interested in the vast databases that sit behind the Outlook.

Where does Australia sit in the pantheon of world economic forces and are we rising or falling in relation to peer nations? It goes to the question that every Australian in property, and in business, asks themselves: is Australia a good place to invest youth, energy, resources, time and effort over the coming decade? Or are there better options out there?

Arise Australia … we’re on the edge of the top 10

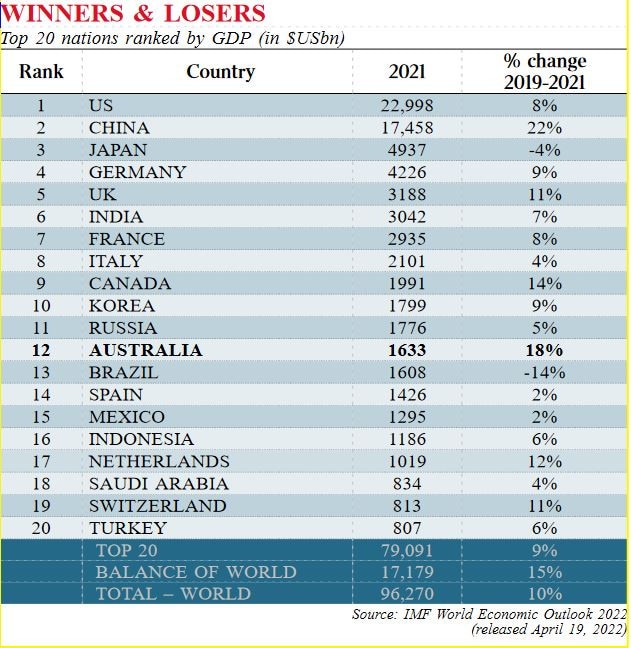

The IMF database covers 190 countries with a combined GDP in US dollars in 2021 of $96,000bn, up 10 per cent from the pre-Covid year of 2019. The Australian GDP jumped 18 per cent over this time frame (in US dollars) to reach $1633bn or roughly 2 per cent of global GDP in 2021.

Australia currently ranks as the 12th largest economic force on the planet, up one spot from last year, having overtaken Brazil (now 13th) and up another spot from the previous year, having overtaken Spain (now 14th). The economies of both Brazil and Spain (along with many others) struggled during the pandemic.

And Australia isn’t too far behind Russia (GDP $1776bn), which was ranked as the world’s 11th largest economy in 2021. Russia has five times the population of Australia which means that, in a broad sense, the average Aussie is five times richer than the average Russian.

This time next year when the IMF delivers its assessment of world economic performance, it is likely that Russia’s GDP will fall even further.

By the end of this calendar year (if not effectively now) Australia could well rank as the 11th largest economic force on the planet, having jumped three notches from the pre-pandemic era. Not a bad effort for a nation of barely 26 million (but with access to the resources of an entire continent).

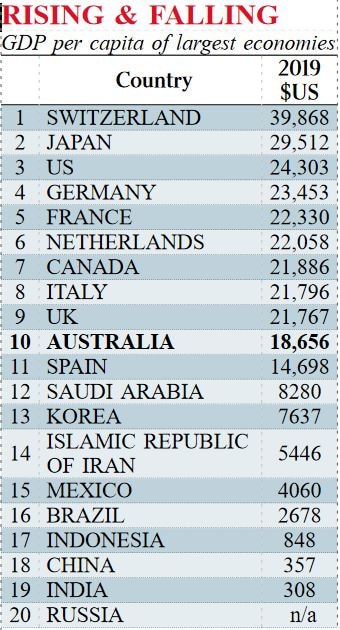

There is no country ranked above Australia with a lesser population. We are really rich per capita when “wealth’ is measured in GDP-per-capita terms.

In fact, the only top-20 countries with a higher GDP per capita are Switzerland (population 9 million, $94,000 per capita) and the US (population 333 million, $69,000 per capita). These figures compare with an average of $64,000 per capita for Australia.

Of course the GDP-per-capita measure assumes equal (or fair) access to a nation’s productive capacity, which isn’t necessarily the case in Australia or indeed in any other country. At best, this measure is a rough guide to the distribution of national income.

Interestingly, Ukraine with 44 million residents pre-war generated a GDP ($198bn) that is about one-eighth that of Russia. Its economy is smaller than New Zealand’s ($248bn).

In 2019, just prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, the GDP of China was 67 per cent of the US economy. Two years later this “gap” had narrowed to 76 per cent (based on data made available to the IMF). Based on these figures China is on track to become the largest economic force on the planet — and in history — at some point in the latter years of this decade.

The IMF reports separate estimates for Hong Kong (“Separate Administrative Region”) and for Taiwan (“Province of China”) and which jointly generated a (US dollar) GDP of $1158bn in 2021. This is roughly equivalent to the GDP of Indonesia ($1186bn).

If for whatever reason these two “provinces” were aggregated with China, then this country’s combined GDP would jump to $18,626bn or 81 per cent of the US economy. At current rates of growth this would place (a greater) China’s replacement of the US as the world’s largest economy at the mid rather than late 2020s. The IMF database does not include data for the Democratic Republic of North Korea, which contains a similar population to Australia (around 26 million). The CIA Fact Book last estimated the DRNK economy at (US dollars) $40bn in 2015, which was 3 per cent of the Australian economy at that time.

The DRNK is a bit like the productive capacity of a Bundaberg, Rockhampton or Mackay (each about 3 per cent of Australia) being spread across all Australians and supporting a military of 1.4 million (as opposed to our 60,000), a nuclear weapons program, and the kind of lavish lifestyle that might be expected by any Dear Leader.

Don’t expand your property business into North Korea.

Across the core pandemic years the Australian GDP increased by 18 per cent, according to the IMF. The scale of this increase cannot be explained by significant currency movements. The only country in the global top 20 to have recorded a stronger percentage increase was China, up 22 per cent (as reported). Other strong GDP-growth performances at this time include Canada, up 14 per cent; Netherlands, up 12 per cent; and Britain, up 11 per cent. On the other hand the economies of Japan and Brazil have not yet recovered to their pre-pandemic levels.

A rising and a rich country … the Goldilocks years

Just over 30 years ago, in 1991, Australia was positioned 10th or midway in a list of the 20 largest economies ranked by GDP (in US dollars) per capita. Indeed our “average income” of $18,656 was positioned between No.11 Spain ($14,698) and No.9 Britain ($21,767).

The richest large economies of this post-USSR-collapse world were Switzerland, Japan, the US and Germany.

A generation later and Australia’s position relative to its peer large economies (excluding Hong Kong, for example) has shifted. We now rank third behind the US and Switzerland and ahead of The Netherlands. Australia’s GDP per capita has increased threefold in three decades.

Income-per-capita jumped even higher in countries that have been transformed by the development of a middle class: China up 34-fold, India up sevenfold, Indonesia up fivefold. But no country, by my reckoning, has jumped higher off an already high base than Australia.

If you have built a successful property business in Australia over the last 30 years it is no doubt a reflection of your skills, business acumen and hard work. But you were also in the right place (Australia) at the right time in history (the 1991-2021 Goldilocks years) offering the right product (housing).

In a general sense the 1990s, the 2000s and the 2010s were good decades to be in the Australian property market. Australia fared better than its peer nations over these years largely, I suspect, because with the advent of globalisation a small, resource-rich nation like Australia could sell (via export markets) far more product than was demanded by the local population base.

Globalisation freed Australia to be far richer than might be expected by our small (and remote) population base. Export markets with China (and others) opened up. We sold residential and commercial property directly to foreign buyers.

We rented newly constructed apartment product to growing numbers of foreign students. And we built hotel and resort accommodation for visiting tourists.

Property was always going to be the favoured industry during these boom (or at least non-recessionary) years. Australians are outrageously aspirational when I comes to housing; we improve and embellish our homes every weekend. These core values drive demand, for example, for big box homewares stores as well as for housing.

But this model of Australian prosperity is predicated on some mightily important assumptions that are now being questioned, if not actively challenged:

● That our national security is assured by the US.

● That our export markets will continue unaffected into the 2020s.

● That Australia continues to get access to skilled labour as required.

● That foreign students will return to pre-pandemic levels.

● That visitors and tourists will return to Australia.

The demand driver for, say, airport property (being the sheer number of Australians travelling overseas) may not fully recover to pre-pandemic levels until later in the decade.

The risk of infection, the ever-changing rules regarding Covid-safe travel, and the ripple effect of the war in Ukraine could well reshape the travel aspirations of Australians. More Queensland, less Europe.

Conclusion … Australia always delivers

And while there is plenty of scope for Australia’s post-Covid recovery to go awry, there is also the undeniable fact that over the last 30 years of unrivalled prosperity, and despite events like the recession we had to have, the Southeast Asian crisis, the Global Financial Crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic, Australia has always managed to recover and has continued to prosper.

I am always inclined – based on the evidence of past form – to back Australia in turbulent times. We’re a good product, we offer a great quality of life, and we recover well from adversity.

I think next year’s IMF report will confirm that Australia is indeed back on track for 2020s prosperity.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; research by data scientist Hari Hara Priya Kannan.

Earlier this month the Washington-based International Monetary Fund released its World Economic Outlook for 2022. Business and politicians (especially in election mode) eagerly await the IMF’s prognostications about the coming year, particularly if it is positive. The most recent report had the Australian GDP growing by a rosy 4.2 per cent in the coming year.