Connecting employment clusters key to more harmonious CBDs

Our workforce is changing as Australia transforms more and more into a knowledge economy.

Our workforce is changing as Australia transforms more and more into a knowledge economy. And these changes have a lasting impact on the physical footprint of our cities.

On a Tuesday in August 2016, you wrote your job title into the box for question 38 of the Australian census. The good folks at the Australian Bureau of Statistics matched your answer with one of 1300 official job titles from The Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC).

Each job classification was assigned a skill level from 1 to 5, indicating how much training you must have gone through in order to practise your profession. Doctors and engineers must study for years before they can do anything — they get assigned a skill level of 1. Cafe workers and sales assistants don’t require any formal training and learn on the job. They get assigned a skill level of 5.

That doesn’t excite you? It should!

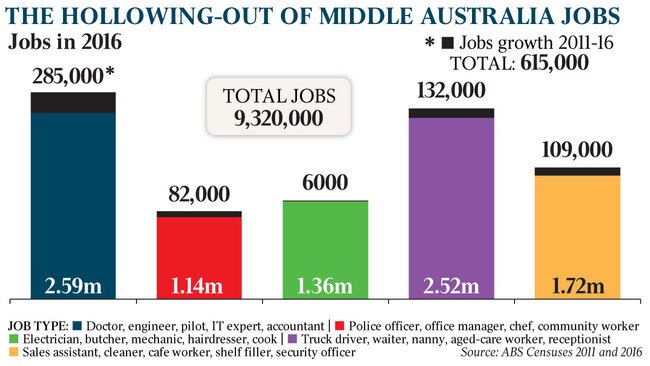

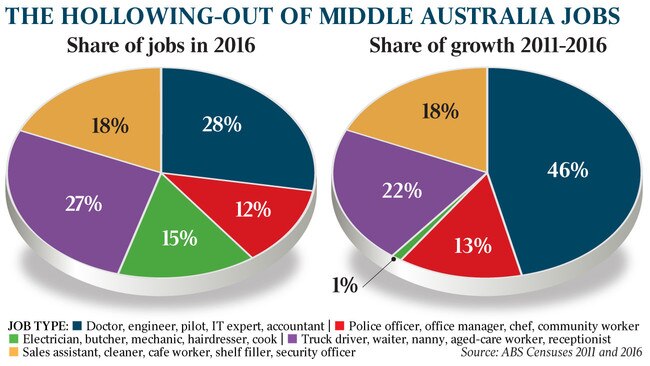

Now we can see what sort of jobs we created in Australia between the last two censuses. While only 18 per cent of all Australian jobs were in the highest skilled category, about half of all the new jobs created in Australia between 2011 and 2016 were classified as skill level 1.

At the same time, we created no net new jobs in the skill level 3 category — that’s the category that is home to most trade and manufacturing jobs. Skill level 3 jobs are considered the backbone of the Australian middle class.

We now see the beginning of a dangerous hollowing out of Middle Australia. These trends are likely to continue over the coming years and will shape the physical and social make-up of our cities.

The skill level 1 jobs tend to cluster heavily in the office towers of our CBDs. Lots of skill level 2, 3, 4 and 5 jobs cluster in the CBD, too. All inner-city workers would love to live close to their jobs to cut back on the daily commute.

Because skill level 1 workers are, on average, the best paid of all inner-city workers, they can afford to live in expensive housing near the CBD, or at least close to the best commuting routes. Lower skilled workers are paid less and consequently struggle to find housing options they can afford in the vicinity of the CBD job cluster.

In the long run this leads to suburbs increasingly segregated solely by income. Fewer of us will live near people in different income brackets than our own. Spatial segregation will be based on income rather than ethnicity.

Of course, there are, and always have been, rich and poor areas in cities all over the world. In itself that’s not too much of a problem. It means, however, that our children visit schools with kids whose parents all match our income profiles. An ever-growing number of us also stopped going to church, a place where people of all social classes built a community and worshipped together.

We have lost opportunities to interact meaningfully with people different from us. That can’t be good news. We know from contact theory that as humans we are likely to harbour negative views against people we don’t interact with, but hold rather positive views of people we have meaningful contact with.

We need to construct more affordable housing for low-skilled workers in and near the CBD. If we don’t do this, we are risking creating a society where high and low-skilled workers both work in the CBD but one group massively out-earns the other, has significantly shorter (and cheaper) commutes and ultimately more spare time to spend with their families.

In such a society the low-skilled workers travel for a long time into the city centre to service the needs of the high-skill-level workers, brewing their coffees and cleaning their offices.

Standing together as one united nation seems an unlikely outcome in a city and society where the rich and poor don’t interact with one another. The good news is, our town planners are aware of the risks highly segregated cities create and try to counteract this trend. They try to strengthen various employment clusters in the city, secondary mini-me CBDs if you will. In Melbourne these would be Frankston, Dandenong, Narre Warren, Ringwood, Box Hill, Footscray and others. In Sydney Campbelltown, Penrith, Liverpool, Parramatta and the new Western Airport region are meant to take the load off the CBD.

The theory is simple: put the high-skilled jobs we will create into the secondary employment centres and people will move to these centres. This takes pressure off residential areas around the primary CBD, drives down house prices and improves traffic flow.

In practice this is a bit more complex. Our plan of strengthening the secondary job clusters is sabotaged by the construction of more office towers in our CBDs — in the case of Melbourne and Sydney the CBDs have been extended by incorporating the Docklands and Barangaroo into the fabric of the CBD.

Companies benefit being close to other companies, clients, banks and so on. This is exactly what we’ve been seeing in Melbourne and Sydney. The CBDs, especially the Docklands and Barangaroo, accommodate more and more very flash new offices. This makes it really hard to strengthen the secondary employment hubs.

If our big cities want to get serious, they will need to slow down construction of new offices in the CBD and build residential towers instead. These must not comprise unattractive one-bedroom shoeboxes but be spacious three and four-bedroom apartments — desirable housing options for workers to bring up their kids in an urban environment. European cities have done this for years.

Such a restriction of office construction would (in theory) drive up prices for office space in the CBDs while making surrounding housing more affordable. High prices in the CBD will make settling in one of the secondary employment hubs financially attractive for all but the biggest companies that will always want to stay in the CBD no matter the cost.

In our interconnected economy, businesses and organisations need to collaborate. This is best done in person. If the secondary employment hub model is ever going to work, inter-cluster travel must be swift and convenient. Allowing for such travel we will need to upgrade our transport networks, be it roads, rail or even some futuristic solution.

If we fail to connect our employment clusters efficiently, the CBD will continue to be the most attractive job cluster and very few big players will be willing to move operations to a secondary CBD.

Secondary employment hubs could help spread high-skilled workers more evenly throughout our cities. For these secondary locations to be attractive office locations for companies, we will need to become serious about upgrading our urban infrastructure. The quality of the transport links between the various job clusters will ultimately decide if the secondary job clusters succeed or fail.

Simon Kuestenmacher is the director of research at The Demographics Group.