When caution is gone then it’s time to worry, but few would argue, even at these lofty levels, that the market has lost its head.

The year is still young and much of corporate Australia is still on holiday so it’s not quite time to pop the champagne.

This bull market, which has carried stocks 47 per cent above their levels of February 2016, is marked by a hefty dose of caution, as shown by the fact Ahmed Fahour at Latitude couldn’t talk his way into a big hand-out last year when his IPO didn’t happen. At the same time there is an absence of outlandish deals in a subdued merger and acquisition market.

Shares are expensive on any score but relativities rule the investment world and a 5 per cent return on stocks compares with 0 per cent on bonds and cash, so there is little choice but to invest in equities.

MST strategist Hasan Tevfik has a price target of 7100 points on the S&P/ASX 200 index by December this year against yesterday’s close of 7041, so investors have almost reached his predicted high.

At a price-to-earnings ratio of 18 times the market is trading above average but below the peak back in the late 1990s when the tech boom pushed the Australian bourse to a multiple of 21 times.

If you think the local bourse has run too hard, the New Zealand bourse, which has a total valuation roughly equivalent to the Commonwealth Bank, is now trading at 27 times forecast earnings.

The Australian market is up 5.2 per cent this calendar year, compared with the total return (which includes dividends) last year of 23.4 per cent. It also compares with the 18.4 per cent gain on pure capital appreciation.

This comes as corporate earnings are tipped to slow and the Australian economy is being slowed by the bushfires. Consensus forecasts supplied by Goldman Sachs show corporate earnings up 4.3 per cent this year against the 4.8 per cent gain last year, due mainly to a slowdown in resources company earnings from 19.7 per cent last year to 9 per cent this year.

Bank earnings this year will be flat after falling 11 per cent last year and industrial company earnings will be up 4.8 per cent against a 2 cent fall last year in present estimates.

The market is trading on a dividend yield of 4 per cent, and for industrial stocks on a free cashflow basis (operating cash less capital expenditure) at 4 per cent, which is on the high side.

But there is no reason for it to crash any time soon.

Heading into the corporate confession season, when those with earnings shocks let the world know, and in a subdued economy, the market is destined to trade on offshore news like the recent US-China trade deal.

The US reporting season is now in full swing for the fourth quarter of last calendar year, which will also influence the local market before Australian earnings are unveiled next month.

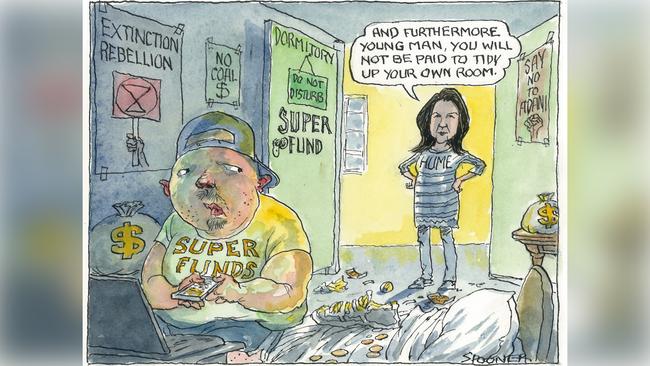

Default super key issue

The federal government has done its bit in helping to tidy up the superannuation industry, and more clean-up work comes ahead of the politically difficult decision on just what to do with default funds and the mid-year release of the retirement incomes review.

The government is framing the review as an information-gathering process, so everyone is using the same data, but some hints are likely on policy issues.

The big one is the planned phasing in of increases in the compulsory income sacrifice from 9.5 per cent to 10 per cent next year to 12 per cent in 2025.

Some favour freezing the take at 9.5 per cent.

The market moved with increased consolidation activity and the big funds are getting bigger with 77 per cent of inflows going to the top 10 last year, up from 65 per cent in 2018.

Australian Super now has $185bn under management.

Financial services royal commissioner Kenneth Hayne and the Productivity Commission both advocated a one-stop default system so you can take your super fund with you wherever your work may take you.

The industry funds want more flexibility, so if your first job was as a bricklayer and you joined Cbus, then moved into retail at Coles you would take your money with you but join REST.

Under the Productivity Commission model you would stay with Cbus but the aim is to remove superannuation from the industrial relations architecture, which makes sense.

Still, the decision is part of a contentious debate over default funds which the government wants to get right at the risk of making it an unplanned election issue.

Financial Services Minister Senator Jane Hume has legislation before parliament aimed at banning mandated default awards which don’t give you the option of going somewhere else. This makes sense because people should have the choice of where they invest their super.

The legislation is in the house and will be put to the Senate after a committee report due on February 21.

Other legislation in progress is the amnesty given to employers who have underpaid superannuation entitlements, as distinct from wages.

Under single-touch payroll the ATO can now work out how much superannuation a company should pay, and under the government bill companies can self-report without incurring a fine.

The ALP wants a penalty, as there is for underpayment of wages.

Industry consolidation is happening, as with recent deals like the $182bn Sun Super and QSuper deal and $125m First Super and Vic Super marriage.

These deals are being encouraged but what is really needed is more tidying up of the underperforming smaller funds.

APRA’s publication of its so-called heat map highlighting continued underperformers was aimed at fast-forwarding that process.

Thanks to government legislation, account consolidation is also happening, with the ATO last year directing some $2.8bn into 2.1 million accounts under the new system where unclaimed accounts worth less than $6000 are transferred to the tax office.

All of this is positive and the big industry funds have easily outperformed their retail competitors, which means funds have poured into the big industry funds.

This has taken some political heat from the debate, because industry funds are seen as better options.

This also means after 28 years they don’t need extra help with default flows from industry awards. But the default market remains a battleground.

At some point the government will make a formal response to last year’s Productivity Commission report on the industry, including its idea that 10 funds should be selected to be the preferred default funds and then be rotated by performance.

The government is not keen on the setting of 10 funds — it would prefer more — but has kept an open mind on the best solution.

A decision on this issue will come later rather than sooner.

The Australian bourse closed on Thursday as the best performing market in the world this year, maintaining a bull run that has lasted almost four years, fuelled in part by a healthy component of cynicism.