Sunbelt drift slows as more of us conclude it's safer to stay put

WHAT on earth is happening in Queensland?

WHAT on earth is happening in Queensland? New figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that net interstate migration to the sunshine state during the September quarter was down 40 per cent on the corresponding quarter the previous year.

And this is on top of three years of successive falls in interstate migration.

Six years ago, in the year to June 2005, Queensland added 94,000 residents, a third of whom arrived from other parts of the nation.

Last financial year, Queensland added not that much less population (89,000), but with barely 10 per cent arriving from interstate. This is an important shift: from 30,000 net interstate migrants a year to 9000 has a big impact on business and, I suspect, state coffers.

Queensland's growth is now underpinned by overseas migration (which is in freefall following policy shifts last year) and an elevated birth rate.

Babies do not directly impact on the demand for housing nor do they work or pay tax - at least not to the extent that interstate migrants do.

Interstate migrants typically buy houses; overseas migrants initially rent. If this assessment is correct, then there would be soft demand for residential property but high demand for rental accommodation.

So what's turning Australians off Queensland? Well, the first thing to say is that it's not just Queensland. Interstate migration to Queensland might have diminished since 2007, but this trend is also true of NSW, Western Australia and South Australia.

And it's not as if everyone is headed for Victoria: that state is more or less holding steady with regard to interstate migration.

No, the fact is that there is simply less of a market for interstate migration now than there was in 2007. Australians are staying put.

I suspect that since the global financial crisis there has been a diminution in consumer confidence and an escalation in anxiety about job retention. No one wants to risk selling their house, buying another house and negotiating a new job in a post-GFC world.

This is very different to the 1992 recession when economic calamity in Victoria stimulated record outflows to Queensland. The difference then was that middle management had superannuation and other payouts that facilitated the deal, and which underpinned the meteoric rise of places such as Hervey Bay.

This time around, super is looking sick and older workers believe there's better value in working longer.

The upshot is a diminution in interstate migration outflows and inflows.

This has affected the demand for property in states such as Queensland and Western Australia, where the economy and property industry have been geared around interstate-migration-supported growth. Take away interstate migration and these states are impacted, Western Australia less so than Queensland because of the mining boom.

But how long will this trend last? The answer is both simple and complex.

The slowdown in interstate migration to Queensland will last for as long as people have diminished confidence in their ability to achieve the shift. There needs to be time and positive consumer and workplace sentiment between the GFC and the recovery.

I'd suggest that, all else being equal, that timeframe would be three to four years, which means that recovery might not arrive until mid next year.

But "demographic recovery" for Queensland could also be tempered by the floods and Cyclone Yasi as well as by further changes in policy settings coming out of Canberra.

And then there is the issue of negative media sentiment, which will continue for as long as the ABS reports show demographic decline.

When the December 2010 and March 2011 quarter migration figures are announced later this year, I suspect that continuing negative figures will prompt yet another round of media angst about the "demise of Queensland".

However, if I am right and interstate migrations to Queensland begin to accelerate from the first quarter of next year, this will not be reported by the ABS until the following September.

The bottom line is that I cannot see anything on the horizon to offer a turnaround view of migration to Queensland within six months, and probably up to a year.

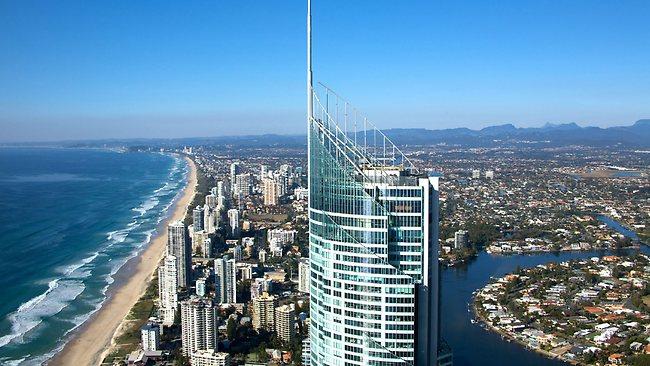

Perhaps because of this gloomy outlook, it is important for business and government to consider the long view: Queensland is the Australian embodiment of the global demographic phenomenon known as sunbelt drift, which we know as sea change.

This trend isn't about to peter out any time soon, and especially with the imminent retirement of the baby-boomer generation.

And while this may be so, the question that remains for many in business is whether they can survive the pain while they wait for demographic rains to arrive.

Bernard Salt is a KPMG Partner

bsalt@kpmg.com.au ; www.twitter.com/bernardsalt

Linkedin/bernardsalt