Imported workers add tax value

Statistics prove our capital cities could not have functioned efficiently without the contribution of foreign-born workers.

This is the story of the demographic and the tax reasons behind the transformation of the Australian workforce.

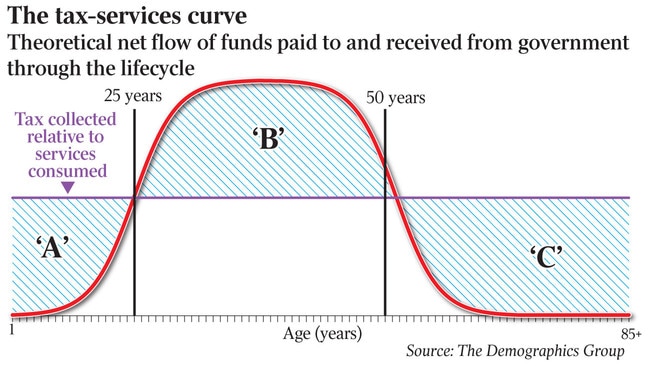

I want to start by introducing my own creation, the Tax-Services curve, which proposes that across the life cycle there are times when you pay more tax than you receive in services, and other times when you receive more services than you pay in tax.

The most obvious recipients of this cross-life cycle flow of tax dollars are kids and the aged, neither of whom work and yet who consume services such as education and healthcare. There must be an equilibrium point where the amount of tax paid equals the value of services received.

The question of whether we are living beyond our means — not raising enough tax or being too generous with services — is answered by the equation where the area of “B” cannot be less than the sum of “A” plus “C”, as in the Tax-Services curve graph.

The equilibrium line rises, falls and tilts depending on tax policy, on our ability to recover tax, on workforce participation rates and on the underlying demography.

Plus, a surplus or a deficit of tax dollars can be carried forward and repaid or drawn down upon over time.

So healthy baby-boomers surging into the 25-55 workforce a generation ago should have produced a surplus that can now be drawn down upon as they push into retirement. The Australian response to the shift in the demographics of the workforce has been to double the level of immigration within a generation.

Here is the blunt truth about our immigration program.

By importing young skilled workers, we avoid having to allocate tax dollars to the Part A (age 0-24) stage of the life cycle, and we reap the benefits of 30 healthy working years, where the volume of tax paid is greater than the value of services received.

Young, healthy, imported workers export tax dollars to kids and to retired Australians.

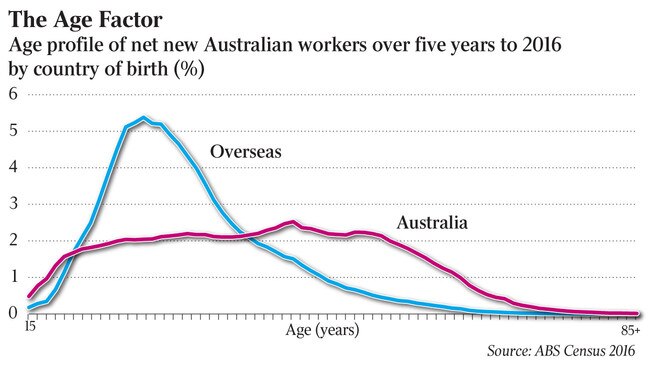

During the five years to the last census, about 169,000 of the 625,000 workers added to the workforce were born in Australia. These locals entered the workforce in greatest numbers between the ages of 30 and 55.

Freshly imported workers, arriving within this same five-year timeframe, outnumbered local workforce entrants by a factor of 2:1. Plus, newly arrived workers were predominantly aged 25-35, which is slap-bang inside the (“Part B”) tax-exporting stage of the life cycle.

Let’s see how the policy of importing young workers has panned out across the Australian urban system between the last two censuses.

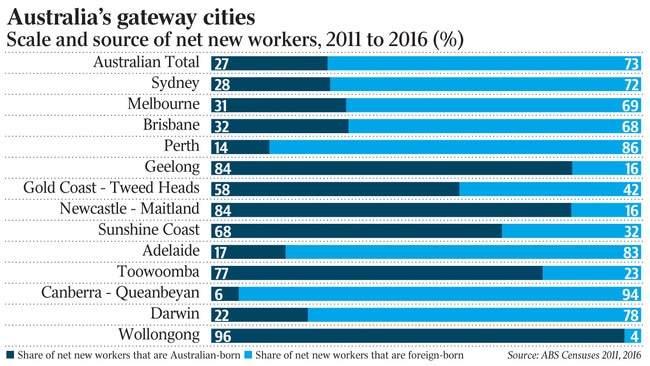

During the five years to 2016, foreign-born workers comprised 456,000, or 73 per cent, of the net new worker population, as measured by the census. The Australian-born component was measured at less than half this figure and represented just 27 per cent of all net new workers.

Without a skilled migration program, Australia would need to have found a net extra 90,000 (mostly skilled) workers every year during the first half of this decade. Some cities rely more on immigrant workers than others. This is especially the case in so-called gateway cities favoured by immigrant workers. These are our largest urban centres, but they can also include rising knowledge or university towns.

During the five years to 2016, the Sydney workforce increased by 209,000 including 152,000, or 72 per cent, of foreign-born workers. For Melbourne, the foreign-born share of net new workers was 129,000 or 69 per cent of the total. For post-mining-boom Perth, the foreign-born share of net new jobs was 54,000, or 86 per cent of the total.

It is fair to say that none of these capital cities could have functioned efficiently without the contribution of foreign-born workers earlier this decade.

I have, in fact, assembled key figures for foreign-born versus Australian-born net new workers across the 25 biggest cities with a growing workforce between the last two censuses. The purpose is to show the extent to which cities rely upon immigration to underpin our standard of living and our tax base. These figures are revelatory.

During the five years to 2016, the Canberra employment market expanded by 9489 net extra workers, according to census data. Foreign-born workers accounted for 94 per cent of this growth.

In the university and, arguably, the knowledge-worker, cities of Geelong and Newcastle, 84 per cent of net new jobs were accounted for by young overseas-born skilled workers.

In Wollongong, however, it’s a different story. Of the 7671 net new jobs recorded by the census during the five years to 2016, just 4 per cent were overseas-born workers. In nearby St George’s Basin (lifestyle communities near Jervis Bay and Nowra) this proportion was 14 per cent, and in Maitland near Newcastle it was 16 per cent.

I think there are gateway cities attracting foreign-born workers and that most of these are capital cities and university towns. However, I suspect that if I continued the analysis to include smaller cities then mining towns such as Karratha would rank alongside Canberra as a gateway city.

And if I look at the country of birth of net new workers in Sydney and Melbourne, an interesting variation is evident.

In both cities more than two-thirds of net new workers during the five years to 2016 were born overseas. And the leading sources of new workers were China and India. However, 11,000 net new workers in Sydney came from Nepal, the harbour-city’s third-largest “new workforce” and yet, oddly, this cohort wasn’t significantly represented in Melbourne.

I think it is the universities, and their marketing programs pitching to potential students in China and India, and in Nepal, that is determining the extent to which immigrant workers find pathways via gateway cities into the Australian workforce.

Here is a cohort and a source of workers that is young, healthy and skilled. They are pouring into the workforce in proportions that are different to the overall population mix where barely one-third was born overseas.

Australia’s capital cities and university towns (and most likely mining towns) are this nation’s gateway cities, and they are vigorously pulling the national demography towards a more youthful, a more skilled, and a more cosmopolitan composition.

Our values and our consumer preferences will be skewed in this direction during the 2020s. The way we eat, the way we decorate our homes, even our beliefs and our affectations, will be reshaped by this Anglo-Mediterranean-Asian-India-Arabic-Nepalese fusion culture spilling out of culturally-powerful gateway cities. Australia is in the unique position of having the capacity and tolerance to accommodate large-scale immigration.

And when you think about the tax advantages at a time of a baby bust, it’s easy to see the value of the contribution that these young foreign-born workers are making to the Australian standard of living and quality of life.

Bernard Salt is the managing director of The Demographics Group. Research by Paul Kelly and Simon Kuestenmacher.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout