The rise, fall and rise of retirees

Over the next decade the baby-boomer generation shifts wholly into retirement. Prepare for a massive shift in consumer and property markets and business.

Deep below the surface of the Australian people there are powerful tectonic forces that can shift consumer and property markets. These forces might stem from the 1960s and earlier, but they are surfacing this decade and will continue into the next.

We all understand the baby boom and its effect on the school-age market in the 1970s, on household formation in the 1980s, and on the demand for sea-change property in the 2000s.

But over the next seven years Australia (and other nations) will pass through a different phase as the baby-boomer generation shifts wholly into retirement.

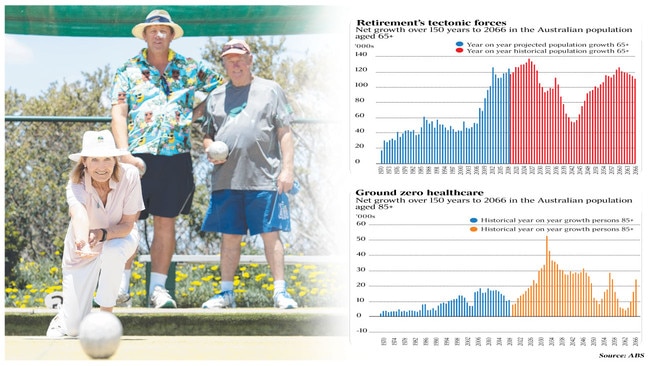

The net annual number added to Australia’s 65-plus population averaged 20,000 over the half-century to 1980. Over the following 30 years this number ramped up to 50,000, but from 2011 onwards the number has jumped to 120,000.

Our rising retiree population results from the inflow and outflow of migrants and the interplay between the number of deaths and the number of people turning 65. Its recent uplift is being driven by a surge in retirees born in the early years of the baby boom (1946-1956) and who are now turning 65.

But the retiree market is also being driven by a global trend of longevity. There’s more people hanging around in their 80s and the 90s, whereas a century ago most people died in their 60s. Longevity, plus the 1950s baby boom, is shaping demand for business, for property and for government services.

It’s tempting to think that “longevity” will increase the retirement population for decades into the future, but this is not the case. The time to be in retirement services — however this sector might be defined — is very much over the coming decade.

The number of Australians annually added to the 65-plus bucket will peak at 137,000 in 2026, then dramatically contract to 54,000 by 2043, and then recover to 126,000 by 2060.

Australia’s retirement population will never actually contract over the next half century, but this cohort’s growth rate will rise, then fall, then rise again.

So, how does all this coming and going of the retirement market affect business and careers today?

Let’s say that you’re in your mid-30s working in aged care, in financial planning, in health care or in the delivery of government services. You entered the workforce in the mid-2000s; you prospered because of the demographic uplift brought about by retiring baby-boomers.

You fight your way to the top of the sector over the next decade as more baby-boomers enter retirement. By your mid 40s you will be at the top of an industry that has expanded every year for 20 consecutive years. It looks like you made a prescient career choice all those years ago.

But then something happens. The market subsides. The skills that got you to the top are no longer relevant in the 2030s. In the decades to 2026 it was all about expansion and getting the model right; in the decade beyond 2026 it will be about cost-cutting, taking market share and managing mergers and takeovers.

This year, and the subsequent six years, is precisely the time to acquire, to build, to invest and to grow businesses associated with retirement, with older healthcare, with life’s later indulgences (for example, cruises), with medical technology such as titanium hips, with the provision of financial planning advice and the development of downshifter properties.

In fact, plan to sell your business in 2026 at the demographic peak of the retirement market.

The time to reduce business and career exposure to this market is in the 2026-2031 time frame, as growth in the 65-plus bucket plummets 30 per cent to 100,000 a year. The retirement sector is still growing, but at a reduced rate.

There is a different skill set required to prosper in a falling market than there is in a rising market.

Throughout the 2030s the strategy might be to acquire distressed businesses and assets in readiness for retirement’s second coming from 2043 onwards.

Maybe the aged-care sector should recruit from the manufacturing sector to get the right skills.

The reason why Australia’s 65-plus market rises and then falls is because of Gen X shrinkage. Rising birth rates between 1946 and 1961 are driving today’s retiree growth. But between 1961 and 1978 the introduction of the contraceptive pill caused birth rates to drop, producing a smaller Gen X cohort following the boomers.

And then of course came the voluminous millennial generation — the children of the baby-boomers — who will boost the 65-plus population from 2043 onwards.

So, there you have it. The reason why there will be a hiccup in the demand for retirement services in the 2030s is because of the pill, which delivered a modest pool of Xers in the 1960s.

But the 65-plus market is actually a grab bag of subgroups that hang around the workforce exit.

It is true that an increasing proportion of over-65s will work, but this will always remain a relatively small number.

At the younger end (65-69) of this grab bag are workers as well as “big trip” travellers, suburban downshifters and an assortment of corporate types in denial and who simply refuse to retire.

The 70s deliver grandparents, legacy-seekers and wellness and enlightenment pursuers.

The 80s and beyond are society’s greatest consumers of healthcare and of a range of government support services.

The 85-plus bucket really is ground zero for the healthcare and the aged-care sectors. There’s about 500,000 Australians aged 85-plus today; this number is currently growing at 10,000 a year in net terms. This market will expand exponentially over the next decade, peaking at growth of 53,000 in 2032.

The strategy, then, should be to continue with the development of retirement homes, the provision of retiring living services, the management of SMSFs, until the mid-2020s and then expand and/or diversify into total healthcare, into delivery of powers of attorney, into ultraluxury cruising, indeed into all of the accoutrement of the dependently aged.

One of the great challenges for business is that from the perspective of age 45 and younger, the 65-plus market looks like a big grey blob. But, up close the market is clearly stratified with each layer being subjected to different demographic forces. Work, superannuation and indulgence eventually give way to family, reflection and legacy, which in turn give way to almost a spiritual preoccupation with the meaning of life.

Business needs to be aware of the big-picture demographics as well as of the segments within the grab bag world that lives, loves and lingers beyond the end of work.

Bernard Salt is managing director of The Demographics Group. Research by Simon Kuestenmacher.