The official interest rate has steadily fallen at the same time as consumer price inflation — the very opposite of what is supposed to happen, according to the conventional economic theory. Lower interest rates are meant to noticeably increase inflation.

Perhaps a more aggressive combination of fiscal and monetary policy might, eventually, be in order, the RBA governor mused after his speech on Wednesday. Right now monetary and fiscal policy are working at cross purposes. The RBA has cut the cash rate to the unprecedented low level of 0.75 per cent to stimulate economic activity, while the federal government has steadily inched up income tax (via bracket creep) to return the budget to surplus.

Playing down the prospect of further rate cuts, governor Philip Lowe called for a debate about the relationship between monetary and fiscal policy.

“We don’t have the capacity to lower interest rates a lot further … Is there more that fiscal policy can do if monetary policy can’t do it?” he asked.

There’s a growing inclination among central bankers globally, frustrated by their impotence outside of pushing up debt and house prices, to push policies that once would have been considered dangerously extreme.

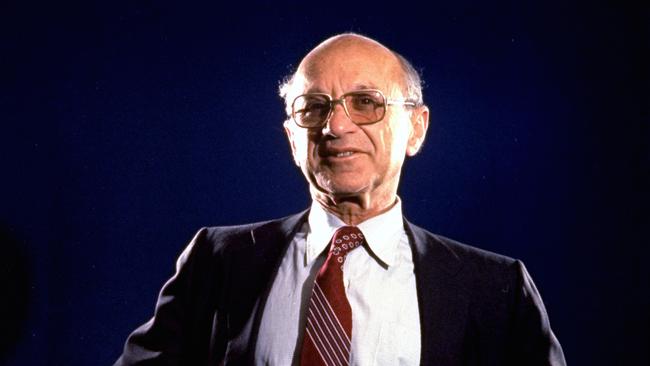

Stanley Fischer, former vice-chairman of the US Federal Reserve and a sort of godfather of central banking, and Philipp Hildebrand, former head of the Swiss central bank, recently proposed a Standing Emergency Fiscal Facility, a fancy form of “helicopter money” — handing out newly created money to boost inflation.

“Any additional measures to stimulate economic growth will have to go beyond the interest rate channel and ‘go direct’ — a central bank crediting private- or public-sector accounts directly with money,” they said.

With central banks having spent decades carving out their independence from treasuries, the future is a blurring of monetary and fiscal policy, it seems. This brave new world will be fraught.

The sports rorts affair, on a small scale, reminds us how ministers might not make the “best” decisions when picking how to spend public funds. The transition from attitudes such as “a federal budget surplus is critical to growth” to “we’re printing money to create growth” will be politically challenging.

All this discussion is premature, however. Growth remains positive, wages are rising, unemployment is falling, and inflation is low and stable — something economists would have considered a windfall combination in previous decades. The RBA is right: the government needs to do more, but it’s in the realm of micro-economic reform rather than setting up another byzantine layer of bureaucracy with dubiously beneficial impact on long-term prosperity.

Buried in the question-and-answer session of the Reserve Bank governor’s first speech of the year was the kernel of a new monetary policy regime. No one has a clue how it will actually work, but inflation targeting with short-term interest rates — the current arrangement — is clearly on its last legs.