With Clough’s failure, Australia does not just lose another engineering company

Clough’s contracts will be picked up by others, but the contribution the company has made to Australian engineering may not.

Whether Clough’s collapse is the result of bad management or bad luck, the impact of its failure eventually will be felt throughout the economy.

Clough’s contracts will be taken up by others, but its traditions may not. And Italy’s Webuild may buy the brand, but there is no guarantee it will maintain the engineering firm’s culture.

Over the years, Clough has trained generations of engineers, building a reputation that all but guaranteed a job elsewhere if the company’s name appeared on a resume.

In its time, Clough hired dozens of graduates each year, and gave them structured training, systems and processes that helped increase knowledge and capability. Even if many Clough people don’t stay, they take their knowledge – and the company’s reputation – everywhere they go.

After starting out life as a home builder, by the mid 1950s the company had taken on contracts to build some of Perth’s first skyscrapers.

In 1957 the company partnered with Danish engineering firm Christiani & Nielsen to build Perth’s Narrows Bridge – then the world’s biggest freestanding, precast concrete bridge – over the Swan River.

The skills and knowledge learned through that partnership helped the company win similar contracts in Western Australia. By the mid-1960s, the company was helping Hamersley Iron (now Rio Tinto) build major infrastructure for WA’s iron ore industry. That was quickly followed by a role helping build the early stages of WA’s oil and gas industry on Barrow Island.

Almost all its projects in a new sector were done in partnership, with Clough bringing in the skills to get the job done, but making sure its Australian work force learnt everything they could to make sure Clough had the capability to bid for the next job itself.

In the 1950s and 60s, Clough boasts that it even employed its own blue collar workforce to do the majority of its carpentry, bricklaying and other trade labour, rather than rely on subcontractors.

The construction industry is a tough place, with little room for sentimentality, and even company patriarch Harold Clough admitted the company could have gone bust a dozen times over its history.

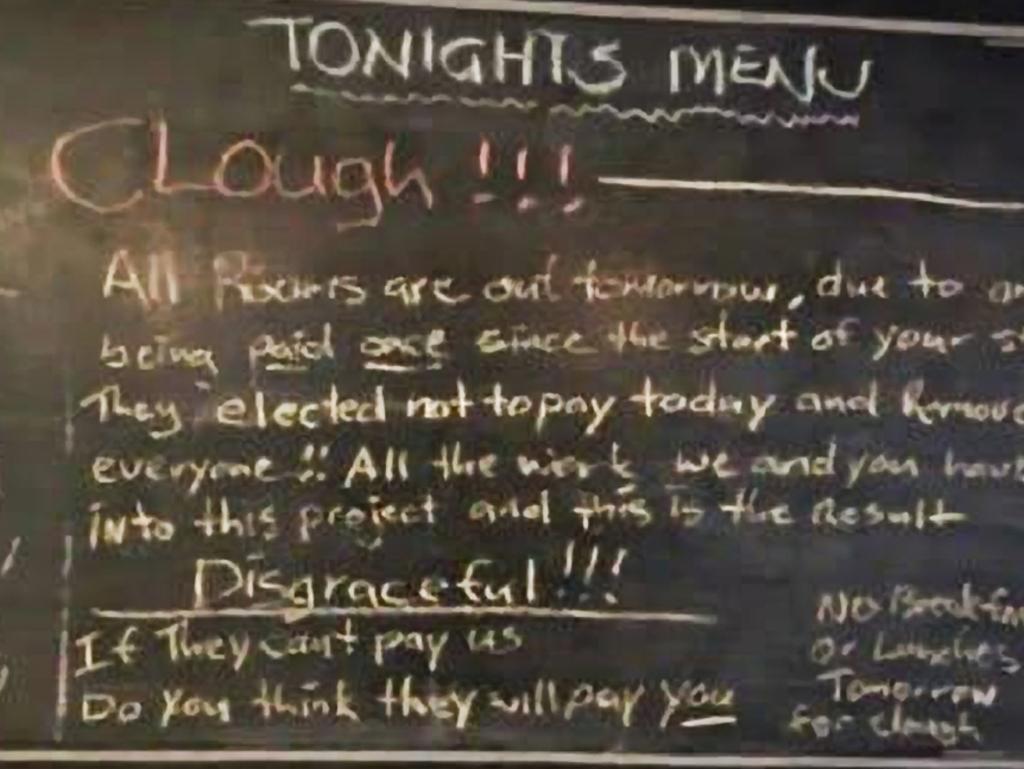

But, until now, it had not. And, judging from the outpouring of sorrow on social media from former Clough workers, the company held a special place in the careers of many.

In an era when engineering can be seen as just one commodity among many, the disappearance of any company that holds up Clough’s tradition of training and developing its own is a major loss to Australia’s engineering capability. As one industry veteran told The Australian, good project managers can save you thousands. Bad engineering will cost you millions.

There are not many homegrown companies like Clough left in the Australian market. A handful of engineering and construction companies remain on the ASX, and only a few unlisted companies of any scale still operate. Industry veterans worry that many are undercapitalised and only a couple of bad contracts away from sharing Clough’s fate.

And few, if any, of the international giants that now dominate Australia’s civil engineering and construction industry can claim to have developed the same kind of reputation for training and development that Clough held for generations.

That matters more than many people realise.

Over the next decade, Australia needs to spend tens of billions of dollars to upgrade its electricity networks and generation assets to end the country’s reliance on fossil fuels. Every business and every household will pay the price if those projects are badly designed and badly executed.

Blue collar jobs are important. But skilled engineers and project managers will be just as crucial to make sure the rollout goes to plan.

That delivery will suffer if Australian capability can’t support the high level of specialised expertise required to get these projects off the ground and keep them on track.

A quick search on LinkedIn shows that former Clough employees didn’t just leave for its rivals, but now fill out the project teams at the major Australian companies that commission and oversee major projects.

Homegrown engineering and construction companies such as Clough are accountable in a way that the international giants will never be. If a major project goes sour, the international majors can simply pick up and move on to another market where the lowest price wins the tender, irrespective of the quality (and ultimate cost) of the work.

And Australia will have few ways to maintain that accountability if it loses the capability – through companies like Clough – to develop the next generation of local talent to compete with them, and oversee their work.

Over the past two years almost every Australian business has suffered the impact of skilled labour shortages and disrupted supply chains.

That will only get worse if any more of Australia’s remaining Cloughs disappear.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout