Production before worker safety for miner

Confidential investigation finds mining giant BHP had a ‘mandate’ to put production ahead of safety.

A confidential investigation found mining giant BHP had a “mandate” to put production ahead of safety, as part of an internal probe into the near-drowning of a dozer operator at one of Australia’s largest coalmines.

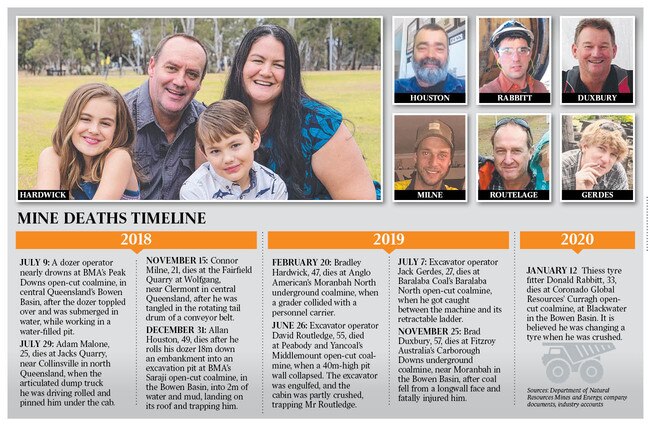

The damning secret report into the July 2018 incident at BHP’s Peak Downs open-cut coal operation in central Queensland raised serious concerns about safety at the company, before a horror spate of eight deaths in 18 months in the state’s quarries and coalmines.

It is believed to be the first written confirmation in the mining industry questioning whether production is the priority, and was delivered to government mining inspectors months before another dozer-into-water accident at BHP’s neighbouring mine killed Allan Houston in December 2018.

Senior BHP officials delivered the document to the Queensland government’s mine inspectorate in August 2018, as required by law after a “high-potential incident”.

The investigators — senior BHP staff from other BMA mine sites — found BHP Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA) mines had no clear guidelines for managing water, despite a history of near-fatal incidents in the industry where bulldozers worked in or near water.

The report described how a 62-year-old coalminer was operating a dozer in a water-filled pit before dawn on July 9, 2018, at the BMA Peak Downs mine. The dozer tipped and the man was trapped in the dozer’s cab as the water rushed in and rose around him, forcing his workmates to smash the cab’s window to rescue him. The Weekend Australian understands the man nearly drowned and now has post-traumatic stress disorder.

BHP’s own investigators questioned why water had not been removed from the pit before the dozer started work, a measure that could have prevented the near-fatal accident. The answer — included in the secret report — has shocked industry veterans spoken to by The Weekend Australian.

“There is a mandate to keep trucks running to meet production targets. There is an asset requirement to have this mandate,” the confidential BHP report states.

The dozers would have had to stop work while the water was removed, meaning the coal trucks would have also had to stop, slowing production.

The investigators went further, finding the company’s strategy “to optimise the mining of coal could have contributed to the dozer operating in water and the event occurring”. BMA told the government it would stop mining in water and review its rules for mining near water.

Months later, on New Year’s Eve 2018, at BMA’s Saraji Mine — next to Peak Downs — Mr Houston, 49, died when his dozer rolled 18m down an embankment and landed upside-down in 2m of water and mud. He was trapped and died.

The government did not issue an industry-wide mines safety alert about the dangers of using dozers near water until after the death of Mr Houston, telling companies to ensure there was adequate protection to prevent equipment from “entering bodies of fluid and where practicable remove the fluid before work commences”.

This week, The Australian revealed the state government had charged BMA and a senior mining official over the death of Mr Houston. Court documents — obtained by Mackay’s Daily Mercury newspaper — alleged BMA’s health and safety procedures for working in and around water were not implemented.

“No risk assessment was completed for the task of dozer push bench preparation,” the documents state. “The presence of water and mud was not identified as a hazard for working being conducted on ramp two.”

Asked about the production mandate, a BMA spokesman declined to comment specifically on its existence. “Safety is the highest priority at all of our sites,” he said.

The spokesman said the company had systems to make sure all findings from internal investigations were shared with other BHP sites. “At each of the Queensland coalmines operated by the BHP Mitsubishi Alliance, we are heavily focused on improving safety, and ensuring everyone is empowered to speak up and take action if they see something unsafe,” he said.

More than 18 months after the Peak Downs accident, the Queensland Mines Inspectorate has confirmed it is investigating new complaints about BMA’s investigation into the incident.

A QMI spokesman said there had been 15 separate inspections onsite at BMA’s Peak Downs and Saraji mines since the July 2018 dozer incident. “The QMI has established that the circumstances were different that led to the incidents involving bulldozers being inundated by water at the Peak Downs mine in July 2018 and the Saraji mine in December 2018,” the spokesman said. “The Peak Downs incident involved a planned controlled movement into the water and the Saraji incident was an uncontrolled movement.”

He said BMA had reported that the dozer operator involved in the July 2018 near-miss had only “a minor hand injury,” and the company had issued a safety notice to all BMA sites later that month that “addressed the controls required to prevent similar incidents”.

Mackay-based solicitor Craig Worsley, who represents the dozer operator nearly killed in the July 2018 incident, said BHP did not convey to the mines inspectorate how serious his client’s accident was. But he said the inspectorate’s response was still “abysmal”.

“Why does it take someone to die to warrant a prosecution? This is a serious near-miss where someone almost gets killed, and (BMA) concede they are putting production ahead of safety,” Mr Worsley said.

He said the company’s production “mandate” cemented the lack of trust workers had in mining companies. “Workers don’t believe the companies have their best interests in mind and something like this (the mandate) reinforces that,” Mr Worsley said.

“After the coal dust debacle and all of these deaths, there is a great trust deficit between the workforce, and these mining companies and the department.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout