Andrew Forrest’s green energy promises hit $200bn

Andrew Forrest’s green energy ambitions have generated plenty of headlines, but they would also come with an enormous cost for the iron ore miner.

Fortescue Metals Group would need to find about $195bn to make good on all of the promises made so far by chairman Andrew Forrest on his global green energy spree.

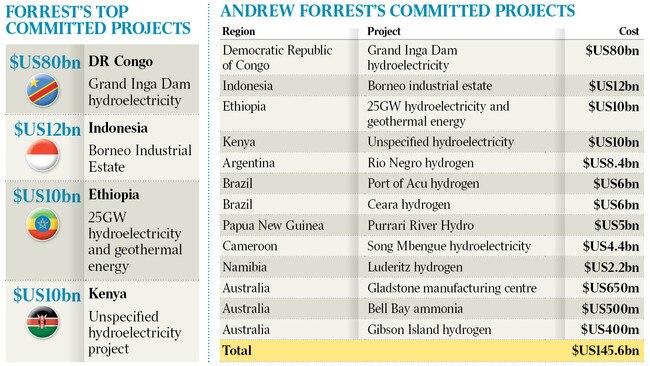

Figures compiled by The Australian show the iron ore major’s green energy subsidiary, Fortescue Future Industries, has inked agreements for hydrogen and renewable energy projects in more than 20 countries over the last 18 months.

While cost estimates are available for only about half of those projects, the total likely cost still comes to a hair-raising $US145.5bn ($195bn).

And that figure is likely to be only a small fraction of the cash needed to make good on Fortescue’s objective of producing 15 million tonnes of hydrogen a year by 2030, with the $US8.4bn cost of a recently announced Argentinian project, producing 250,000 tonnes of hydrogen a year, suggesting the final total could balloon past $US500bn.

The amount of capital needed to make good on the projects where estimates exist underlines growing concerns among Fortescue’s major investors and financial analysts about the speed and scale of FFI’s global commitments as well as the projected return on investment.

Fortescue has been keen to note that no final investment decisions have been made on any of the projects in its stable, and chief executive Elizabeth Gaines told The Australian the company had “clearly articulated its capital allocation framework and has guided to FFI expenditure in the range of $US400m to $US600m for FY22”.

“We have previously disclosed that all proposed projects will be developed by FFI with ownership and project finance sources to be secured separately without recourse to Fortescue,” she said.

Ms Gaines said Fortescue had only so far committed to spending about 10 per cent of its net profits on FFI projects, while maintaining its current dividend policy, as the company stretches towards the extraordinary goal of producing 15 million tonnes of hydrogen a year by 2030.

On Fortescue’s last two quarterly analyst briefings, Ms Gaines has been pushed repeatedly to outline the business case for the company’s move into green energy and hydrogen production, with senior investors demanding Fortescue give shareholders a full briefing on its plans and the likely impact on future returns.

But, while the company maintains its position that it will make full market disclosures when final investment decisions are made on green energy projects, capital estimates worth more than $US145bn have been put on the public record.

Some cost estimates have been given by government officials after meeting with Dr Forrest and FFI, such as the $US12bn for Fortescue’s contribution to a proposed industrial estate in Borneo given by Indonesia’s Co-ordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, Luhut Pandjaitan, in August.

Similarly, in June, FFI reportedly signed a memorandum of understanding with the government of Cameroon for the development of the Song Mbengue hydro-electric project, with local media reports referring to government estimates of a cost equivalent to about $US4.4bn.

And in April a public post by a Namibian government agency said FFI was investigating the construction of a $US2.2bn hydrogen project in the harbour city of Lüderitz.

Fortescue has disclosed an indicative cost of only one of the FFI projects to shareholders to date, over plans to build a hydrogen electrolyser manufacturing plant in Gladstone, Queensland, where it says it will make an initial investment of about $US83m and a total of “up to $US650m”.

But Dr Forrest and FFI executives have repeatedly gone on the record with cost estimates when speaking to the media. The list is topped by the $US80bn Grand Inga hydro-electric project in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Dr Forrest signed an agreement with DRC President Felix Tshisekedi.

But Dr Forrest confidently told reporters at the time, while discussing both the Grand Inga project and earlier agreements with the governments of Kenya and Ethiopia, that Fortescue “will invest on behalf of itself and its supporters over $US100bn developing the top hydro, solar and geothermal sites in Africa”.

Dr Forrest has also cited likely construction costs for FFI’s proposed green ammonia facility in Tasmania and those related to its plan for a hydrogen plant at Incitec’s Gibson Island fertiliser plan.

And only last week FFI head of Latin American operations, Agustin Pichot, told reporters at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow that FFI would need to spend about $US8.4bn to build a proposed green hydrogen plant in Argentina’s Rio Negro province that would produce about 250,000 tonnes a year.

Sources say those figures, the first available to match capital costs with likely hydrogen output in the FFI project stable, sent shockwaves through institutional investors holding Fortescue stock, given its output would be only a 60th of the 15 million tonnes a year it wants to be producing by the end of the decade.

If the Rio Negro estimate is indicative of the cost of other projects around the world, it suggests about $US504bn in capital would be needed for Fortescue to make good on its ultimate ambitions.

Analysts and investors are also quietly expressing concerns that Fortescue will need to rapidly accelerate spending in the next few years to have any hope of reaching its 15-million-tonne goal by 2030, given it has not released details of the technology it plans to use.

But even the timetable for FFI’s most advanced project, a 250-megawatt green hydrogen plant capable of producing 250,000 tonnes of green ammonia per year in Tasmania’s Bell Bay area, appears to have slipped.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout