Trent Dalton: ‘I think I’ve only just realised why I do this’

For years, journalist and author Trent Dalton has sat in strangers’ living rooms. Why does he so badly need to hear their stories?

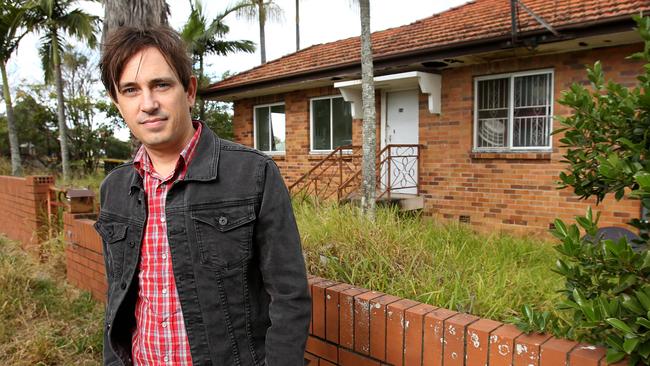

Finally, after more than 15 years as a journalist, countless memorable pieces, multiple awards and his first highly acclaimed novel, feature writer Trent Dalton, 39, is starting to realise why he does what he does.

“I think I’ve only realised why I do this,” he tells The Australian’s Behind the Media podcast.

“I keep asking myself why am I going into these living rooms across Australia. My job as a long form journalist, I go into these living rooms and I sit with people for four hours, and I just sit and listen.

“And I’ll just sit there and listen and listen and listen some more and at the same time I’m doing that, I’m looking at their walls. I’m searching for clues about their lives. I’m looking at various things around the living rooms and I’m always asking myself ‘why am I doing what I do? I need to hear the story so bad, right?’”

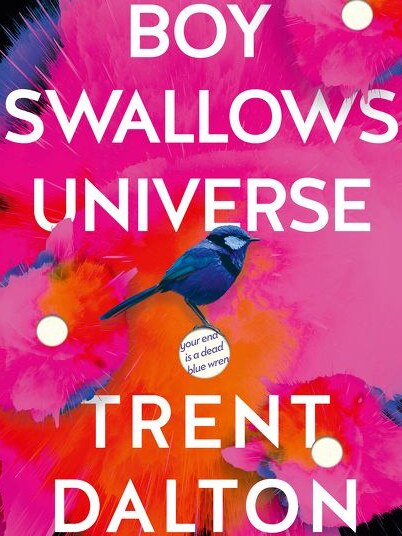

It took the writing of his 470-page novel, Boy Swallows Universe, inspired by his “somewhat nutty life”, to get his answer.

“I’m realising that I’m there trying to work out my own shit.”

Dalton’s colleagues testify to his ability to focus, to concentrate his mind on the task at hand and his Stakhanovite work ethic. His journalism is often about domestic violence, victims of crime, the bereaved, a father who tracks down the six people who received his dead son’s organs, the wartime history of his family.

He admits his pieces can be very emotional. “I put so much freakin' heart and soul in them that I’m bloody crying sometimes as I’m writing and I think it’s some sort of catharsis that I’m going through for myself. It’s a little bit batty but it’s kind of it’s very inspiring as well.

“And I think I’m trying to be candid, to get the scoop on my own family, on the very people who I love the most in this world.”

Some journalists attest that they turn to writing a book because the story they feel compelled to tell can’t be confined to journalism. It is too big, too profound, each time they stuff an edge of it into a report or feature, another part spills out the other side.

Thus Dalton’s own life story is loosely retold in the novel Boy Swallows Universe, a humorous and compassionate story of the chaotic childhood of Eli Bell. His brother is mute, his mum is heading for jail, his dad’s a drunk, his stepdad deals heroin, oh and his babysitter is Arthur Slim Halliday, Queensland’s most famous prison escapee.

The novel had wonderful things to say about families, about brothers, but is also a homage to Brisbane and to the 1980s (Sale of the Century at 7pm, ETA Five Star margarine).

But the book is also about journalism. In it, the young hero Eli Bell is talking about his older, mute brother August’s love of details — “how to read a face” and extract as much information as possible from the non-verbal, how to mine expression and conversation and story, “the things that are talking to you without talking to you”. “It was August who taught me I didn’t always have to listen, I might just have to look.”

Dalton is a master wordsmith, but more than that, an emotion whisperer. In the hours he spends with his subjects, they tell him their secrets in a steady stream of extraordinary profiles and interviews in The Weekend Australian Magazine, and before that the Courier-Mail’s Q Weekend, which he joined after his first job on the weekly property glossy Brisbane News, after a creative writing journalism degree.

He is utterly genuine when pitching for an interview. “Here’s why this piece I am going to write is a little bit different,” he tells people on their door steps, such as serial killer Ivan Milat’s brother Alex, or Chantelle Newbery, the Olympic diving champion, who became a drug user.

“I’ve lived with desperate people and I’ve lived with people who’ve seen some shit as well so I understand what you’re going through. I don’t know whether that comes out in the way I’m talking or the way my eyes look or this sincerity on my face. But oftentimes there’s a pause and they’ll size you up and they’ll open that friggin' door and that’s a beautiful trust exercise.”

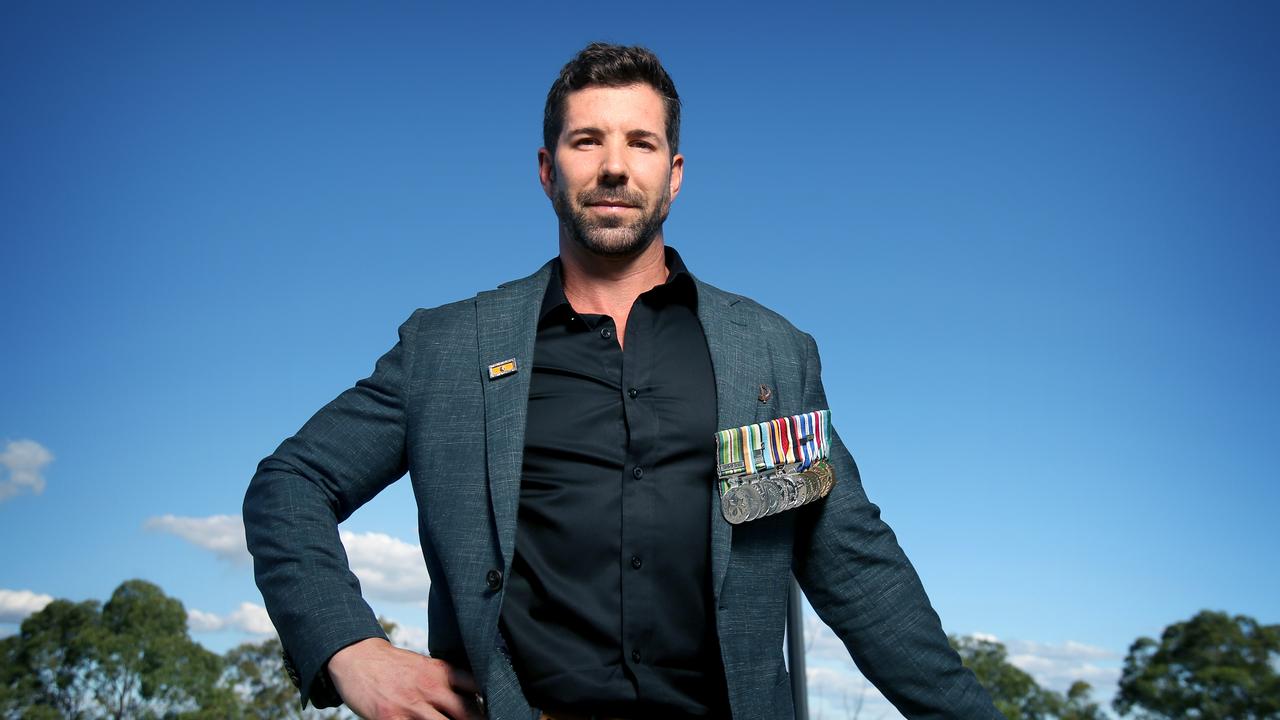

That was on Thursday, and it is now Sunday and I am trying to apply the Dalton techniques. August would be disappointed in me. What was Dalton wearing? A checked shirt (I think). How did he react when I questioned him? His body language is now a blur. All I am left with is a shock of dark tufty hair (black, I think?) and resolute pale blue (?) eyes that reveal his all encompassing ambition.

Everyone who encounters Dalton, including the sales assistant at my local bookshop, know how nice he is, and note his infectious enthusiasm. So when Dalton sits down and admits to an ambition, it’s something of a shock.

“It was really in full frickin' tilt in my 20s. I was this ambitious sort of blustery journo, trying to write a masterpiece or something.

“But I was this blustery guy who would kind of hurt people

“I do have this adherence first of all to the reader. The reader comes first, as opposed to the subject. Give them every piece of information at all costs you know, and even if that action actually hurts the subject so be it — that’s journalism right?”

Age has not wearied him, but one incident did change him. His worst moment in journalism was ringing a doorbell to do a story on a mother who had lost her son, not realising she was cradling his ashes inside. They had just arrived.

He wrote a handwritten letter of apology. He very often stays in touch with those he writes about and once even hired a van to help an interviewee move house.

“I don’t know whether I’m starting to be a more rounded human being or more rounded journalist. I’m starting to realise you can do both. You can serve both and kind of write a cracking story that gives people everything, but still a subject reads it on a Saturday morning and it doesn’t have it doesn’t have to ruin their life.”

Afterwards, a colleague, Greg, asks how the podcast went. I confess that I lost control of the interview. Greg smiles, either encouragingly, or to point out my essential superfluousness to quality of proceedings. “It will still be good though.”