That year, in pre-budget briefings, this newspaper was told of extraordinarily high superannuation accounts, some with balances in excess of $100m.

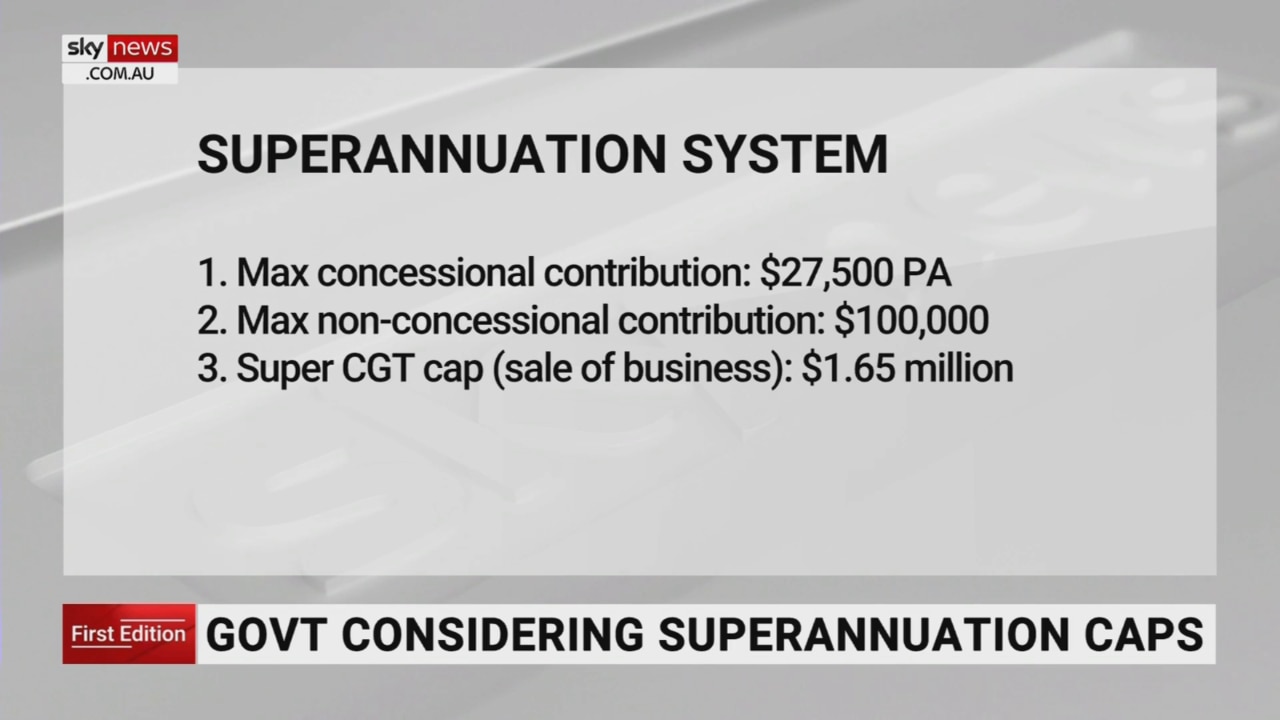

Reforms since then have capped such large contributions. Former treasurer Scott Morrison changed the non-taxable upper super benefit limit to $1.6m in 2017.

That is indexed regularly and is about to be lifted to $1.9m.

Many conservative journalists campaigning against winding back tax concessions seem to have forgotten the abolition of a 15 per cent tax on superannuation disbursements – as legislated in the original implementation by Labor treasurer Paul Keating – only dates back to Liberal treasurer Peter Costello in 2006.

That reform also allowed one-off deposits of up to $1m.

Journalists at the time knew it was too generous.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s economics editor, Ross Gittins, wrote on June 19, 2006: “The tax concessions for super have always been biased in favour of higher-income earners; these changes make them more so.”

The tax rate on funds exceeding the pension limit is 15 per cent less franking credits, so between 7.5 and 10 per cent on average.

Young families struggling with rising mortgage rates may pay top income tax rates of 45 per cent plus the 2 per cent Medicare levy while wealthy retirees can pay zero on $1.7m today and 7.5 per cent on amounts above that.

This really is tax minimisation to preserve wealth for retirees’ children rather than a retirement income system. In that sense Sky News Australia business editor Ross Greenwood was correct last week when he likened the effect of Labor’s proposed reforms to an effective death tax.

Yet estate preservation and tax minimisation were never the purpose of compulsory national super.

Can anyone really make a case for the largest self-managed super fund – $410m – as revealed by The Australian Financial Review on August 30? That’s some retirement.

Perhaps journalists should ask the question this newspaper’s former economics editor and now Washington correspondent, Adam Creighton, has been asking for several years: Is the system really worth keeping?

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese promised several times before last May’s election that in government he would not change the rules of super. This is as clear a broken promise as voters will ever see.

Is Treasurer Jim Chalmers really motivated by the small revenue gains Treasury expects from limiting the preferred tax treatment of super balances to a maximum of $3m?

The political damage of this broken promise hardly seems worth the $1bn a year in revenue it will save. The government may calculate only 36,000 people will be affected but the optics will appal millions of voters.

Few journalists have ever made the case but Labor’s real aim is shoring up the industry super funds run by its union mates, after the Morrison government allowed people to dip into their own super during Covid.

The opposition now wants young people trying to get into the housing market to be allowed to do the same to boost deposits.

This is anathema to Labor grandees such as Cbus chair and former Labor treasurer Wayne Swan, Hesta chair and former Labor attorney-general Nicola Roxon, Australian Super chair and former Keating chief of staff Don Russell, CFMEU super fund First Super’s co-chair, Michael O’Connor (a long time leader of that union), and Industry SuperFunds chair Greg Combet, a former senior minister in the Rudd and Gillard governments.

Yet this is not about jobs for the boys and girls. It’s about the way industry funds assess their growth rates without investing much in liquid assets.

As this column argued on April 6, 2020 when discussing Scott Morrison’s decision to allow access to super during Covid lockdowns, the market for CBD property preferred by the industry funds is not liquid in the way the share, bond and money markets are.

Industry funds are potentially vulnerable to a heavy flow of withdrawals because their assets are not easily sold, especially in bear markets. Traditional retail funds invest much more in liquid assets.

Rudd government former economics adviser Andrew Charlton, the new ALP member for Parramatta, gave the game away on Sharri Markson’s new program on Sky last week. Charlton said the Morrison government’s decision to let people access $20,000 of their own money was the real trigger for Chalmers’ proposed reforms.

“This is an effort to safeguard the future of super, not to change the rules on people. The rules were changed … over the last three years when the Morrison government ripped a hole in the bottom of super and during the pandemic allowed $36bn to flow out,” Charlton said.

Labor politicians love talking about the beneficial effects of compound interest rates on super and the need to preserve benefits through a worker’s life. But compound interest works both ways.

When Chalmers talks about super funds investing in social housing and renewable energy, he is raising the possibility of less than optimal “financial” decisions that can have negative effects on lifetime investments.

Add a related anomaly. Why prevent young people from accessing their own super to buy a home they can own but allow their money to be used for social housing likely to underperform in the wider housing market?

Even former Reserve Bank governor Bernie Fraser, no friend of the Coalition, criticised the idea. Fraser told this masthead on Wednesday: “I can’t believe (Dr Chalmers) would be arguing for funds to invest in social projects, for example, which have pretty low rates of return.”

Home ownership for most people is a strong predictor of a happy retirement. Remember the average male retiree leaves the workforce with $210,000 in super and the average female with $146,000. But the median home price in Sydney in the December quarter was $1.4m. Super industry analysts say a comfortable retirement savings target for a single should be $545,000 and $640,000 for a couple.

This raises a key issue that journalists squib. Has compulsory super actually worked for most people?

Chalmers last week regularly quoted a $48bn figure for the total annual cost of super tax concessions by 2050, which would by then exceed the cost of the aged pension. A more damning figure springs to mind.

Despite a $3.3 trillion national super pile, 70 per cent of Australians still retire on the Age Pension. That is down only 10 per cent over the 31 years of the scheme. Most Australians still receive a full or part pension.

AFR economics editor John Kehoe on Thursday pointed out that by 2060 total pensioner numbers would fall only to 62 per cent of retirees but there would be only 2.7 taxpayers per retiree compared with four now. The ageing of the population will force a rethink of a system.

No surprise that by the end of the week self-interest trumped principle among politicians.

Teals MPs in rich former Liberal-held seats told Friday’s AFR they opposed the super changes. But rich former Labor politicians on generous super schemes notionally worth much more than the floated $3m limit told this newspaper the changes that won’t affect them are fair.

Both sides of politics have been looking at changing the treatment of high superannuation balances since the Abbott government’s 2014 budget.