Grounded Greste grapples with freedom and airports

He saw a fellow reporter killed. He was jailed in Egypt. Peter Greste is as determined as ever about press freedom.

Journalist Peter Greste was released from an Egyptian prison more than 2½ years ago after a 400-day incarceration on trumped-up terrorism charges, but he is still a prisoner.

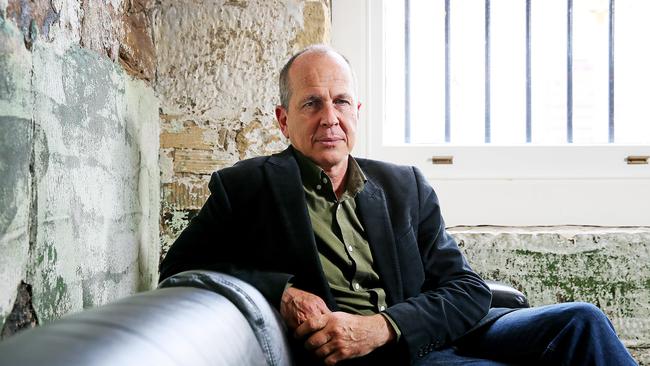

To meet the famous journalist (a tag he hates, but how many journalists get stopped in a newsroom by people wanting to shake their hand?) now is to find a man looking happy and healthy and glad to be alive, but one whose career and purpose have been taken away.

The former BBC and Al Jazeera reporter cannot do what he wants to do, which is resume his career as a globetrotting foreign correspondent. For one thing, his fame (he still hates the word) gets in the way of his reporting. Assignments become weirdly inverted, people want to ask him the questions (prison life is a favourite) instead.

Then there is his status at the airport immigration counter. “There’s another problem quite beyond the fame and that is that I’m a convicted terrorist,” Greste says in an interview with The Australian. “I have an outstanding prison sentence to serve. And so any country that still has an extradition treaty with Egypt is technically a problem for me and that’s not an insignificant number of countries.”

Officially, Greste, 51, was extradited from Egypt after he and two Al Jazeera English colleagues, Mohamed Fadel Fahmy and Baher Mohamed, were found guilty of spreading false news, among other terrorism-related charges. The Egyptian government eventually released the trio, but never formally cleared the men.

So he is still regarded as a criminal in Egypt and countries with which it has an extradition treaty. That includes most of the Middle East and the whole of Africa including Kenya, a place Greste has loved for 10 years and made a home.

Nairobi is a long way from his current domestic life on Sydney’s lower North Shore with his partner, Christine Jackman, a former journalist on The Australian, and her two sons. Greste shies away from the tag celebrity journalist, but he will leverage his recognition to campaign on press freedom, not just in the Middle East but here at home. In his new book, The First Casualty, Greste calls out the Australian government’s attempts to push through metadata retention laws as a curbing of press freedom.

“I feel passionate about press freedom issues more broadly,” he says. “If I have the credibility that comes with that experience to talk about these issues then I’m going to use that. I don’t see any reason why I shouldn’t — it’s a great opportunity and I feel quite determined.”

Greste is also in the midst of a book tour to promote The First Casualty. So is his role now to ask questions, or answer them?

“I would hope that I can get back one day to being just reporter Peter Greste in the field, out there doing the job that actually I’ve loved for such a long time. ”

He has filed reports for the ABC including Foreign Correspondent and an excellent Four Corners on the rise of Facebook. He has a documentary series planned with the ABC next year, as well as some long-form filmmaking.

“I’m planning to keep going with my journalism even if it is in some altered form,” he says.

There is another major impediment. “I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to get into the United States with a terrorism conviction?” he asks.

Greste has. He ticks the box on the form and tells Homeland Security the truth and they “send in the storm troopers”, as he puts it, half-jokingly. Actually, higher-up authorities know about his case and treat him well, but each entry into the US is a long process.

If it gets very awkward, Greste has a further truth: former president Barack Obama campaigned for his release from Egypt. But, “I haven’t tried to get in under the current administration. In fact, if challenged, I will have to see how that rolls”.

But right now there is his book to promote, a memoir about his time on the road and in prison, and also a treatise on the state of press freedom, or depressing lack of it. It recounts the time Greste was standing next to his BBC producer colleague Kate Peyton in Somalia in 2005. He remembers the moment she was shot “as clear as a bell”. The pair were reporting from Mogadishu on the return from exile of the Somali government, and had exited a hotel to return to their car. The street was full of armed bodyguards

“There was an open street,” Greste says. “It wasn’t sealed off but it seemed safe enough anyway. There was a single crack, a gunshot. Everyone hit the deck to see if there was any more gunfire.”

“I didn’t really quite understand what had happened. And I feel like some idiot had just let fly a loose round. And I stood up and saw Kate slumped across the back of her vehicle moaning quietly and I went round to her as if to say, ‘You know it’s OK. You know it was just a loose round.’

“She put her head against my shoulder and I rubbed her back and said, ‘Look, it’s fine. Don’t worry about it.’ Blood came up on my hand and I saw the stain spreading across the shirt.”

Peyton was rushed to hospital but never recovered from surgery. She was the first Western journalist killed there in a decade and it became clear her murder was a targeted killing against the media. Did Greste experience a yes or no moment at that point?

“No. I was never ready to give it up again, partly out of bloody-mindedness, I guess. I felt that if I walked away because someone wanted to silence journalism, then I would have given up and I would have been dishonouring Kate’s legacy.”

Greste, like many journalists who place themselves in danger, is not in it for the thrill. “I don’t think of myself as a risk taker. I don’t think of myself as an adrenaline junkie or a thrillseeker.

“And I’ve said this to my parents several times ... listen, you need to understand that I am aware there is a risk here and we do everything we can to reduce the risk to a level that I feel comfortable with. But you can never eliminate that risk entirely. The only way of eliminating it is not to go. And I’m a journalist. This is what I do. (It) is these stories I believe in. I feel that we should be covering them. We need the balls to go and do that.”

The First Casualty, his book’s title, comes from the historical saying: the first casualty of war is truth. But Greste argues it is no longer just the truth. In the war on terror, he says, the first casualties are now journalists ... Kate Peyton, Daniel Pearl and many others.

“I think the two are connected. You know if you want to kill the truth, kill a journalist. Those two things are very closely intertwined,” Greste says.

So he will continue to ask the questions, mindful of how the war on terror has made his career more difficult than ever thanks to the bullets of terrorists but also the actions of our governments determined the fight them.

The book makes me pessimistic, but not Greste.

“While we might be in a bit of a trough at the moment,” he says, “I still think that if you look at the course of human history we have moved inexorably towards more openness and freedom.”