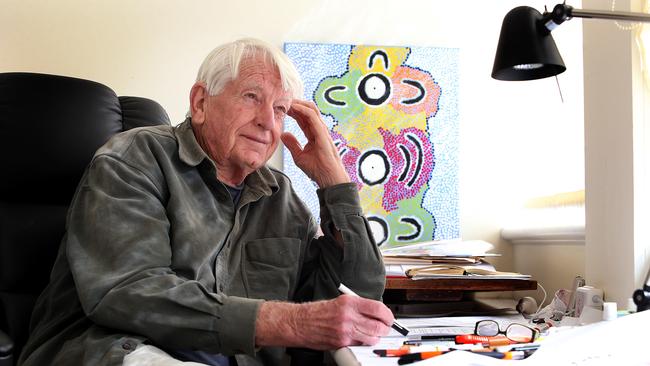

Bruce Petty, who died last week at age 93, was one of Australia’s greatest cartoonists

Political cartoonist Bruce Petty’s frantic, free-flowing style was unique; his insights were anxious and penetrating.

Donald Horne’s 1964 book gave birth to the ironic phrase The Lucky Country. Often misconstrued, it described an unadventurous nation, whose second-rate leaders were a conformist subset of Britain’s.

In 1964 all but one of Australia’s state governors was a retired British army officer, so too the Governor-General, Viscount De L’Isle.

In business, politics, the arts – but with the possible exception of science – Australia was intellectually unambitious, a prematurely weary country of also-rans for whom the intrepid were a menace.

Its broadsheet newspapers reflected the frayed cliches of orthodox publishing. Not long before, The Bulletin had finally removed the banner from beneath its masthead “Australia For The White Man”.

Three men changed all that: Rupert Murdoch, Maxwell Newton and Bruce Petty.

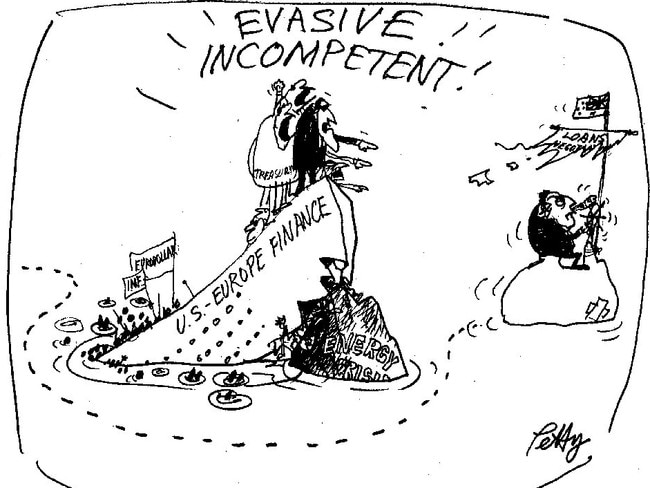

Murdoch was the brash media upstart who dreamt of a truly national newspaper; Newton was the aggressive Cambridge-educated editor first to understand that, when it came to reporting, economics and politics were indivisible; and political cartoonist Petty, whose frantic, free-flowing style matched nobody’s, and whose insights were anxious and penetrating.

They were in their mid-30s and, each having spent years abroad, understood how meekly provincial Australia was ruled by a too-seldom-scrutinised elite in Canberra and big-city boardrooms whose unseen apple carts were firmly anchored. The comfortable system needed prodding, the apple carts upturning.

The launch of The Australian in 1964 helped begin that process with a message for the future.

The Australian would be vibrant, insightful, thoughtful and irreverent, but with faith in the nation it believed would do much better. It led by example, employing the first female press photographer.

But it was Petty’s daily cartoons across more than a decade in these pages that bound those notions so convincingly together.

Liberated by The Australian’s thinking in those early days it took a while for Petty to find his style, but the signs were there from day one.

On the day The Australian launched, the country’s long-serving prime minister Robert Menzies – who would describe himself as “British to my bootstraps” – was in London at the 13th Heads of Commonwealth Meeting. He was not too often chastened by newspaper cartoonists, but Petty was off the leash.

Eleven days earlier, Australia had lost its first son to the Vietnam War. The Coalition parties were fractious and a wounded opposition leader was lashing out.

Petty’s first cartoon had two panels: in the first, a genteel Menzies addresses the Commonwealth leaders grasping two documents – How I Do It and Easy Politics.

The second panel “back at the ranch” shows a riotously aggressive group including Liberal divisions, an indifferent Country Party and an explosive Labor leader Arthur Calwell, labelled the “socialist tiger”, at war.

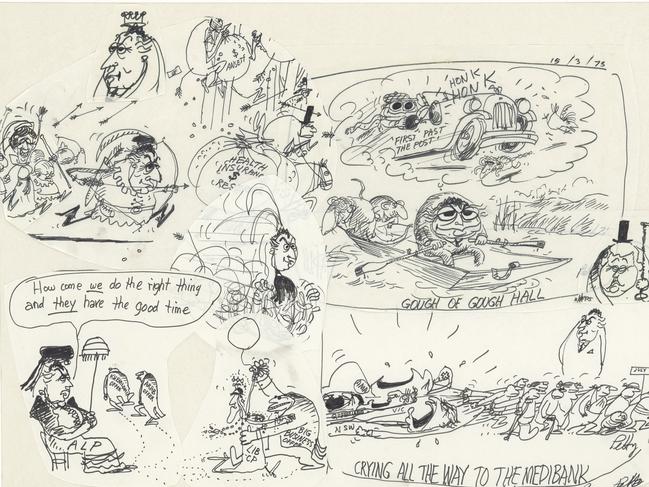

Petty would refine his insights – they would become more acute – but never his urgent, disjointed scribbling style that he fashioned after the Polish illustrator Feliks Topolski, who moved to London and whose draughtsmanship was described as a “multiple, moving, complex, varied, intoxicating agglomeration of mankind”.

Topolski would say of his controversial style: “I feel I must make it clear that my work is neither ‘academic’ nor caricaturing on the basis of photographs — it is done from life”.

Petty had encountered Topolski’s drawing while studying at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in 1949 and working at the Herald & Weekly Times photogravure printworks.

He had already dabbled in animation with the 1948 educational short film Careful Koala.

Soon he was in London, in time to see Topolski’s fortnightly illustrated broadsheet Chronicles.

He submitted cartoons to Malcolm Muggeridge, then left-wing editor of the esteemed Punch magazine. He was published there and later in the New Yorker and Esquire.

Returning to Australia he worked in advertising before landing a cartooning role with Sydney’s Daily Mirror, where he made a name for himself, setting up the move to The Australian.

Bruce Petty: From the mind of a cartooning master

He was often asked about that first night, but remembered little: “I do remember Max Newton beaming and trying to explain difficult economic things to people like me.”

It worked.

And Petty blazed a trail followed by the greats of this country’s newspaper cartooning, including Larry Pickering, Bill Mitchell, Peter Nicholson, John Spooner, Bill Leak and, these days, Leak’s brilliant son Johannes.

Petty’s definitive cartoon was published on Saturday, April 26, 1969. The nation’s Anzac Day marches took place the day before.

The first Vietnam moratorium protest was a year off, but anticonscription feelings were rising along with the death toll of Australians, 102 of whom died in Vietnam in 1968, our costliest year.

At the centre of Petty’s cartoon was the image of an outsized dead and mutilated Digger. Marchers, much smaller than the main figure, approach, skirt and then march away from his body barely glancing at it.

Consumed with their own opinions of war, they chant about the glory of national pride and sacrifice, or question, and perhaps mock the loss.

Petty would go on to a feted career at The Age and win a Walkley Award for the most outstanding contribution to journalism.

He was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Melbourne Press Club and is in the Cartoonists’ Association Hall of Fame.

He famously “won” an Academy award in 1977 for a short film he directed (precedent ordered that it went to the producer).

His colleague and friend, John Spooner, whose cartoons these appear regularly in The Australian said Petty’s cartoons “had tendrils of thought that reached across the political landscape”.

Spooner, a three-time Walkley winner and an Australian Journalist of the Year, believes Petty’s Vietnam works were landmarks in cartooning’s influence of the national debate.

And he had been listening to his editor: “He imagined and drew a Newtonian (Sir Isaac, not Max) world of levers and pulleys that illustrated the pseudoscientific jargon of economics.”

While they were at The Age, Spooner said Petty did not have a designated desk, just settling on one in the art department. He drew with a felt-tipped pen on sub-editors’ layout sheet:

“You could always tell Bruce had been there by the pile of words and scraps of imagery scattered across it. By then he was gone.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout