GFC 10 years on: The day the music died for the world economy and capitalism

On the 10th anniversary of the GFC, key figures reveal the unthinkable action they took to pull Australia from the precipice.

In the Reserve Bank’s Martin Place eyrie the mood is pessimistic. And the regulator closest to the financial markets, the punk music-loving Guy Debelle, thinks the line of 1980s gloomsayers classic This is the Day — “you didn’t wake up this morning cos you didn’t go to bed” — best sums up the time Australia stared into the abyss.

“My memory of all of this is somewhat hazy … it’s like the 60s, if you can remember it you weren’t there,” Debelle tells The Weekend Australian.

“One thing I think which was remarkable particularly towards the end was just the number of decisions being taken by people who were just completely sleep-deprived,” he says, referring to the US officials he was in near daily contact with.

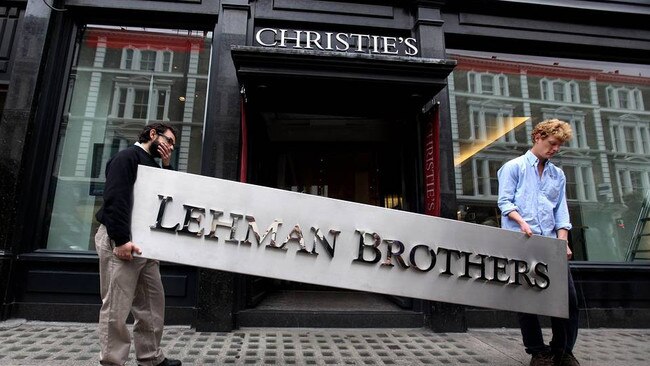

It was the watershed event of the 2008 financial crisis. A weekend-long meeting of the most powerful bankers in America and treasury secretary Hank Paulson failed to come up with a rescue for one of Wall Street’s oldest firms.

As Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in New York at 1.45am on Monday, September 15 — 10 years ago next Saturday — the global economy was plunged into its worst crisis since the Great Depression 80 years earlier.

Suddenly a waking nightmare that had been building in the belly of the US mortgage market seemed too large for even the government of the world’s biggest economy to handle.

Lenders froze, demand for cash soared and markets plunged as the first ravages of a global recession were felt.

In Australia, within two months the collapse of Allco Finance Group — which in 2007 led a takeover bid for Qantas — would add to a casualty pile that already included securities lender Opes Prime and would go on to include Babcock & Brown and ABC Learning.

Before the worst had passed the Australian sharemarket would halve in value, funds would be frozen and debenture funds would collapse.

Tony D’Aloisio, then chairman of the Australian Securities & Investments Commission, estimates $60 billion to $80bn of wealth was wiped out in panic selling and corporate collapse. “There was a lot of pain, I recall, and we were obviously very, very busy,” D’Aloisio says.

Around the developed world unemployment would soar, economic growth slump and deficit spending would explode as governments and central banks attempted to cauterise a problem the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the early 1930s.

An existential crisis for capitalism? “It was, for that period between Lehman falling and around December, I guess,” say Glenn Stevens, who’d taken the reins as governor of the Reserve Bank in 2006.

“If capital markets are closed, if everybody globally and locally is thinking I’ve got to pull back, get my money out, curtail expansion, bunker down and survive, that’s a very serious threat,” he says.

And yet Australia outran it. A mixture of luck, preparation, and decisive action by regulators and legislators pulled the economy back from the precipice.

This week the country marked 27 unbroken years of economic growth since the 1991 recession.

How did we do it? And can we do it again?

In a series of interviews with The Weekend Australian, key regulators say they were forced to consider and then put in place previously unthinkable measures to stop a financial markets contagion infecting the real economy and avoid unemployment and a recession.

Even now, debate continues to rage about whether the kitchen-sink approach by policy makers went too far, let alone what the long-term consequences will be.

Stevens is adamant it didn’t.

“I think when it’s a confidence event, the risky strategy is to say, ‘well let’s not try and do too much, let’s do a bit and see if that works and then if it doesn’t we’ll do a bit more’,” he says.

“That time didn’t last very long, probably only six or eight weeks, but in that period I think the decision-makers were not going to die wondering, ‘Should I have done more?’ and that’s probably right.”

Within weeks of the collapse official interest rates in Australia would be slashed by an outsized 1 per cent — the most rapid change since the RBA started inflation targeting in the early 1990s. It was the first of four moves totalling 3.75 per cent in four months and set rates on their way down to the emergency levels that persist today.

“If there’s ever been a moment in the past 50 years of doing more than might be needed, that was the time,” Stevens says.

Bank deposits and wholesale borrowing would be guaranteed — a revolution in the nation’s financial history — while short-selling of shares was banned. Two days after the October rate cut prime minister Kevin Rudd announced a $10.4bn stimulus package aimed at shoring up the housing industry and consumption.

As the contagion spread from the finance industry to the real economy through the end of 2008 and into the New Year, a second package totalling $42bn and including $950 cash payments to eight million Australians, was launched in February 2009 in a bid to keep money circulating and avoid a spiral of unemployment. Cynics said it was about keeping GDP growth figures positive in the first quarter, thus avoiding the technical definition of a recession. Whatever, it worked.

“Australia could go into recession or we could go into deficit,” said former treasurer Wayne Swan, then less than a year into the job.

The strategy, according to the then Australian Prudential Regulation Authority chairman John Laker, was to encourage people and banks to keep spending and lending. “Policy makers can’t sit back and say, well, let’s wait and see when the crisis hits,” he says.

“The strategy was aggressive but authorities pursued it because that was the right thing to do.”

The numbers inside the banking system told a terrifying story. The money banks kept on deposit at the RBA exploded from less than $1bn to more than $15bn in the aftermath of the Lehman collapse. Demand for cash soared in early October as Australians pulled $5.5bn from the banks. The RBA was forced to print another $10.6bn in $100 and $50 bills to keep up with the demand. The cash drain was most pronounced at regional banks Suncorp and Bankwest where deposits slumped by $1bn and $2bn respectively.

For Laker, the week leading up to the guarantee was the crux of the crisis for Australia. “That’s when it all came to a head, through the genuine fears of Australian banks that their treasuries would not be able to continue their long-accustomed access to wholesale funding. And that was frightening,” he says.

Ireland moved first, guaranteeing its banks’ wholesale liabilities on September 30. Within 10 days, Denmark, Germany, Britain, Belgium and Spain had followed suit, and then Australia on October 12.

A series of regulatory strokes of the pen had destroyed the idea banking was a free market. At its height the commonwealth was guaranteeing about $170bn of bank borrowings — on top of deposits — making a tidy profit along the way of about $4.5bn.

The changes were particularly dramatic in Australia, which hadn’t even guaranteed deposits. “It was left ambiguous, some might have said constructively,” muses Stevens, referring to the wide gulf between what the man in the street thought and the legal reality.

Preparation had also been important. Australia’s system of regulating banks had been overhauled through the experience of the state bank collapses in the early 1990s that led to the creation of APRA, carved out of the RBA, and the 2001 collapse of insurer HIH, which had been so big and pervasive that it chipped economic growth and stalled activity across parts of the country.

APRA wore part of the blame for that collapse and Laker came to office with a clear expectation he would provide “firm touch” regulation.

Swan, then a rookie treasurer for a new Labor government, said the US treasury-driven shotgun wedding of the troubled Bear Stearns with JPMorgan in March alerted the government to more turbulence.

“We knew something was wrong, but we had no idea just how bad things were going to be,” Swan says.

Through the middle of the year the government legislated a new Financial Claims Scheme (in addition to wholesale borrowings) and powers to take over stricken financial institutions if it needed.

By October, at an International Monetary Fund meeting on October 8 — three weeks after the Lehman collapse — “things were absolutely appalling”, Swan says. The global financial crisis had intensified as global credit dried up and business confidence plunged.

In the December quarter of 2008, businesses ran down stocks by $3.4bn, the largest fall on record, while consumer confidence plummeted.

For markets it was a time of extreme confusion: just why had Lehman been allowed to fail, when just about every other major financial company had been merged or bailed out — at least since Continental Illinois in 1984 — investors asked. The Federal Reserve even organised a bailout of Long Term Capital Management, a hedge fund, in 1998.

Just a week before that gathering of bank chiefs at the New York Fed, the government had been forced to rescue Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, with a $US200bn injection of preferred stock.

A week after Lehman’s collapse it pumped $US85bn into giant insurer AIG, which had sold many of the credit default swaps that underpinned the mortgage market. Those default swaps were among the financially engineered products that had fuelled the mortgage lending boom. Loans were offered to ever-lower quality borrowers and parcelled up by the lenders to be sold on to investors, with insurance that gave them an “investment grade” credit rating. Within days the US government would unveil the mother of all rescues, a $US700bn plan to mop up souring loans on the books of US financial institutions, known as the Troubled Asset Relief Program.

Swan says treasury secretary Hank Paulson had been scarred by the backlash following the previous rescues and wasn’t willing to follow them with another.

Plans to have Barclays take over Lehman were ditched when its home market regulator, Britain’s Financial Services Authority, refused to bless the deal.

Bank of America pocketed stricken Merrill Lynch for a knockdown $US50bn — half its value just weeks earlier.

“But Lehman was so big it brought the whole system down,” says Swan. “They did intervene with AIG a week later because they didn’t want it to happen again.”

In Australia, financial institutions had little direct exposure to the toxic products that were unravelling in the US and Europe.

National Australia Bank would reveal $1.7bn of securities on its balance sheet and Basis Capital Alpha fund was blown up after buying into a package of Timberwolf collateralised debt obligations — the famed “one shitty deal” sold by Goldman Sachs and exposed by the US Senate panel hearings.

Higher interest rates in Australia — the RBA had been leaning against rising inflation since 2007 with interest-rate rises starting at the November 2007 federal election — meant banks and investors had no need to go chasing dodgy assets. But there was contagion. Global financial markets became unwilling to lend to any institution that had the word bank in its name, Laker says.

“There was a very pronounced contagion effect, which swept up Australian banks notwithstanding their fundamental strength and high credit ratings. That’s why the government guarantee was pivotal,” he adds.

“Lehman Brothers made the markets realise that there are limits to the government’s ability or inclination to bail out a bank.”

Unlike the US, where more than $US1 trillion was spent bailing out the banks, Australia had focused its efforts on making sure they didn’t fall over in the first place.

Laker regards the rate cuts as one of the most important steps. The dominance of variable-rate lending meant that a cut to official rates could act as a direct transmission of cash into borrowers’ pockets and keep them spending.

It was the unprecedented scale of the cuts that grabbed attention. Debelle, now the deputy governor of the RBA, was then the regulator closest to the financial markets. Minutes of the October board meeting show Stevens had initially planned to ask the board to approve a cut of 50 basis points. But it went harder at Debelle’s urging.

“I have some memory of being on the more pessimistic side because of looking at all this crap happening in the markets on a high frequency basis. Sometimes stuff that happens in the markets matters and sometimes it doesn’t and people in the markets overegg the real economy consequences,” Debelle says. “This was not one of those times.”

From 7 per cent in September 2008 rates would tumble 3 per cent by April 2009 in a bid to keep money circulating. They rose again through late 2009 but the sluggish growth brought on by the after-effects of the GFC would see rate cuts resume in late 2011 through to August 2016 when they hit 1.5 per cent and stayed there.

As Australia this week marked 27 years of unbroken economic growth, the record shows the country avoided recession but its financial markets and budget were hammered.

And it was swept up in decade-long global reforms to brace the financial system against a repeat of the 2008 catastrophe.

The sweeping re-regulation across the financial services industry continues, with measures to address bank capital, executive pay and market incentives.

Scholars debate furiously the adequacy of the re-regulation. Far from shrinking the industry, financial services’ share of the economy has grown from 8.5 per cent in June 2008 to 8.8 per cent in June this year, near an all-time record.

The banking royal commission has shown incentives to maintain customers by acting in their interests haven’t been as strong in finance as in other sectors.

“The mere existence of deposit insurance doesn’t guarantee that depositors won’t try to get to the counter ahead of others,” Laker observes, referring to the first bank run in a century in Britain that saw Northern Rock customers queued up for hundreds of metres along the street. “If nothing else, those images taught banks not to set up branches with small counters close to the street,” he adds.

Globally, banks have fought proposals from experts such as Hyun Song Shin, Mervyn King or Anat Admati, that would substantially reduce their leverage, size, or implicit subsidies. Memories are fading and scars are healing already. “One can only hope they don’t fade too quickly,” Laker says.

“It’s always tempting to think that things are going well and it must be our genius and I think it’s a fatal trap to fall into,” Stevens adds.

“You don’t want no risk-taking … we’ll alternate between greed and fear, that’s the human condition.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout